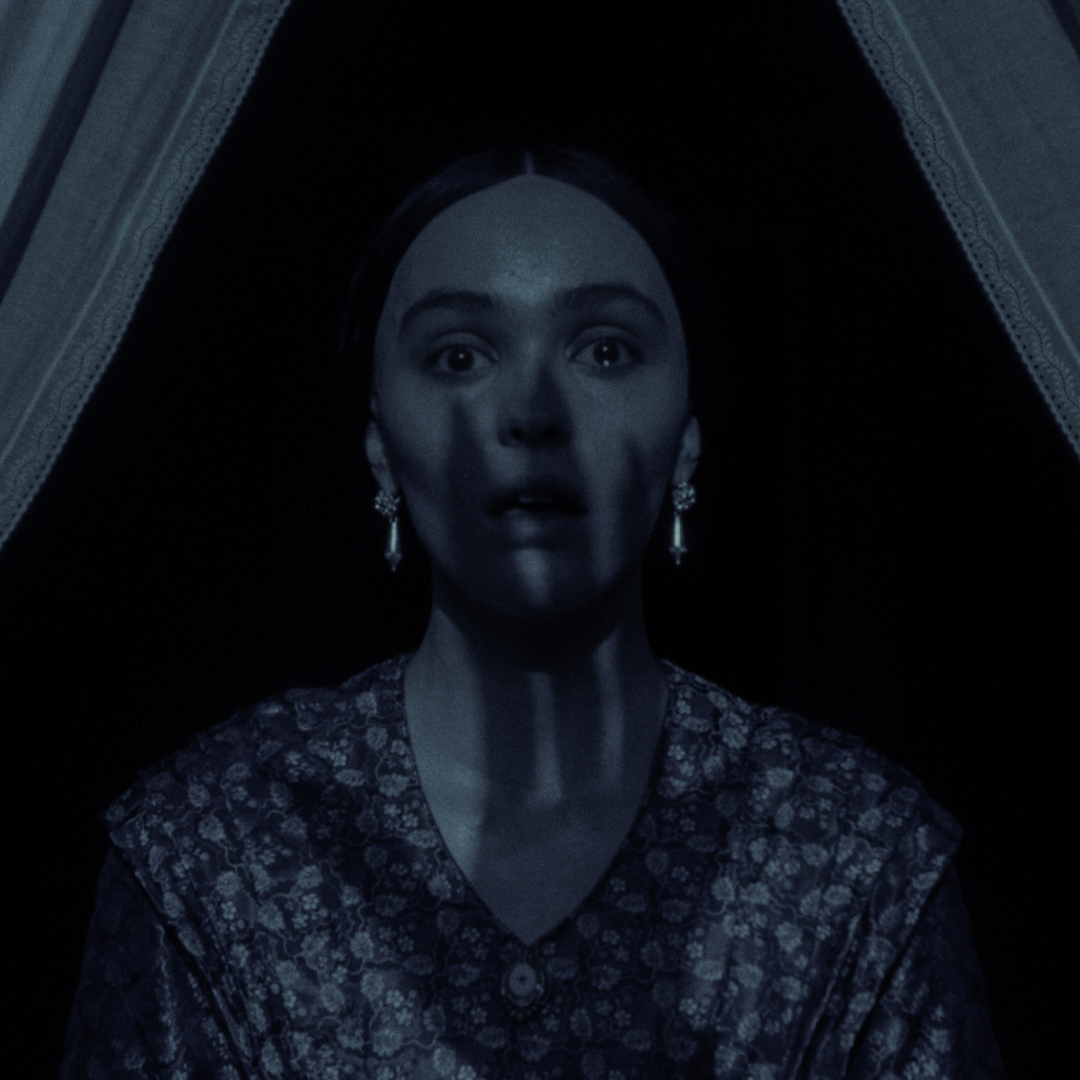

This story contains heavy spoilers for Nosferatu. Every night her husband Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult) is away, Lily-Rose Depp’s Nosferatu character, Ellen, has nightmares about the vampire, Count Orlock. She convulses, sleepwalks, and moans as if something has come over her. Though Orlock (Bill Skarsgård) is vile, the erotic dreams force her to be curious about a side of herself that she’s been told to repress—and clearly no longer can.

During Robert Eggers’ remake of the classic gothic tale, the 19th-century housewife works through her shame even while men try to diagnose and hospitalize her, and Depp’s portrayal is one of cinema’s latest, greatest erotic horror performances. The 25-year-old is on par with Isabella Adjani in 1981's Possession (Adjani also played a version of the Hutter character in a 1979 rendition) and Charlotte Gainsbourg in 2009's Antichrist. But while her predecessors are completely unhinged in their characterizations, Depp straddles a fine line of literally being in a corseted and tightly bound body, while emotionally wanting to rip open her bodice and give herself over to the “darkness.”

Much of Depp’s bewitching performance in the film, out December 25, comes down to her movements, from granular gasps to dramatic back arches. To manifest believable moments of possession and sexual awakening, Depp worked closely with movement coach Marie-Gabrielle Roti, a visual artist with a background in dance. A close collaborator of Eggers’, having previously worked with him on 2022’s The Northman, as well as shows like The Witcher, she was tapped for this project due to her knowledge of the Japanese dance form butoh, known as “the dance of darkness.” (It’s often a source of visual inspiration for many J-horror films.)

Roti choreographed movements before shooting, relayed them to Depp during a rehearsal period in the production’s stunt room, and was present throughout filming on the snowy Prague set. She also helped craft the final sequence between Ellen and Orlock, just before the set was closed to the two actors, an intimacy coordinator, and the director.

Most notably, the movement coach saw herself as further elevating the project’s “feminist lens.” “The messages that come across [in the film] are about female desire, female eroticism, and medicalization of the female body, ” she tells Marie Claire over Zoom from her home in Suffolk, England. (The town is coincidentally known as “witch country,” due to its history in the U.K.’s witch trials.)

“There are still things that women don't talk about with each other or admit to. In different cultures, it's completely taboo, or your body does not belong to you to a certain extent. It belongs to your husband or to the patriarchies,” she says. “For Ellen to find her way through all of that and then to reach her own conclusion was an interesting journey to take with her.”

We spoke to Roti about finding inspiration in hysteria patients from 19th-century mental hospitals, how surprised she was by Depp’s flexibility, and constructing the film’s final intimate scene between the monster and Ellen.

Marie Clarie: You studied images of hysteria patients for inspiration. Were there certain photos you were looking at? Did you give Lily-Rose Depp any homework?

Marie-Gabrielle Roti: Yes, over the course of that whole rehearsal period, both Rob [Eggers] and I would give her images. In fact, Rob's office had massive blowups of images.

When I go to create movement, I'm drawing upon a massive reservoir of visual images that have embedded themselves in my body. So, I was very aware of some of the images of the arch of hysteria—where women do these extraordinary backbends on the bed. There was one particular patient of [neurologist Jean-Martin] Charco's, called Augustine, who was very famous for doing these.

I was also equally aware of the wonderful visual artist Louise Bourgeois, a French artist in her 90s, and she's done a lot of sculptures called the “Arch of Hysteria” dealing with these images of women in cages or domestic spaces. For me, that was a perfect image to work with.

What I do is I go into a studio, I have these images, I have these references, and I have Rob's script as the primary focus. I'm reading the script carefully, going, ‘What does he need in this particular scene?’ Rob works so beautifully in terms of visualizing and [storyboarding], so everything seems to be there. But funny enough for the movement, [he can be] quite open-ended because he realizes that the body has to find its place in the frame. So, that was my job.

MC: You specialize in the Japanese form of dance butoh, which greatly informed Lily’s movements. Why was butoh so inspiring for this film?

MGR: I think of myself as an artist working with the body, and I think of choreography as painting the space with movement or sculpting time with movement. Butoh [for years after it was founded in the ‘50s was] quite male. Women only became involved from the 1970s onwards. Part of my work within butoh has also been to work as a feminist marker to think about How can this language be used to explore my own body, my own desire, my own eroticism, my own sexuality, my own darkness, my own shadow? How can I use all of these things as a language and as a tool to go inside and to express, not just on behalf of myself, but on behalf of other women?

Butoh was perfect for Nosferatu because it deals with transformations of the body. In some senses, we open the body to being inhabited by various forces, whether that's wind, rain, becoming a flower, an insect, or an animal. In the same way, Nosferatu is about allowing an entity to manifest. It felt like it was destiny that those two languages should meet somehow.

MC: That’s so interesting and makes sense since this version of Nosferatu sees Ellen through a feminist lens and more than a sacrificial lamb.

MGR: I was really interested in the medicalization of [Ellen’s] body. That's why both Rob and I leaned into looking at notions of hysteria and the documentation of hysteria in the 19th century, which tallied extremely well with the period in which [the film] is set. I was thinking about how that body is literally corsetted in. It's repressed, it's controlled, it's laced up, it's buttoned up—and how Lily might work against that and try to find her way out of it in some form.

MC: Did Lily-Rose Depp surprise you in any way while you were working together?

MGR: Lily was always a revelation. I remember that first rehearsal we were doing a lot of shaking—and shaking is quite exhausting. I remember Lily saying to me, ‘Marie, do you do this for a living? Oh, my God, this is really hard!’ But once we developed a language together, and she understood what was required, then she started to settle into it and find ways to be able to cope with the demand on her body.

I was surprised at her flexibility. I said to her, ‘How come you are so flexible? Do you do yoga or something?’ She said, ‘No, nothing.’ She's more flexible than the average dancer in her back and elsewhere. So I was able to go, ‘Right, that's it. Beautiful. I can use the arch of the hysteria.’

The scene [when she arches her back and levitates off the bed] we made very quickly. And then Lily insisted on putting her hand on [her neck]. It made sense—we had her hand there at the beginning [of the film].

MC: Was there a moment in rehearsal when the movements began to click for her or did it all come as naturally as the backbends?

MGR: It took a few rehearsals to find the core strength. The opening scene where she's lying in the earth on her side, that takes an awful lot of core strength to find the stability not to faceplant. When you have to roll onto your side, it's quite an art to keep the core steady so you can shake, hold this hand here, and shake your legs at the same time. So that took quite a few rehearsals, but once she got it, [she got it].

The scene that was the hardest was this shaking scene where she was with her husband in the living room. This was really hard because, in a way, it wasn't 100% choreographed. It wasn't like, ‘Put your hand here. Do that.’ It was more like she had to find a physical state inside of herself, which we can rehearse, but there's only so much you can rehearse before you have to do it along with the text and the actions of demolishing the living room. It was incredible how she managed to do that and find all the transformations. In the end, it’s Lily who has to glue it all together for herself as an actress and find all those little nuances.

MC: Was she rehearsing with you in a corset?

MGR: I was absolutely insistent from the very beginning that we work in a corset because I was very aware it would impact her ribcage, movement, breathing, but also bring its own beauty to how we might then deal with the movement itself.

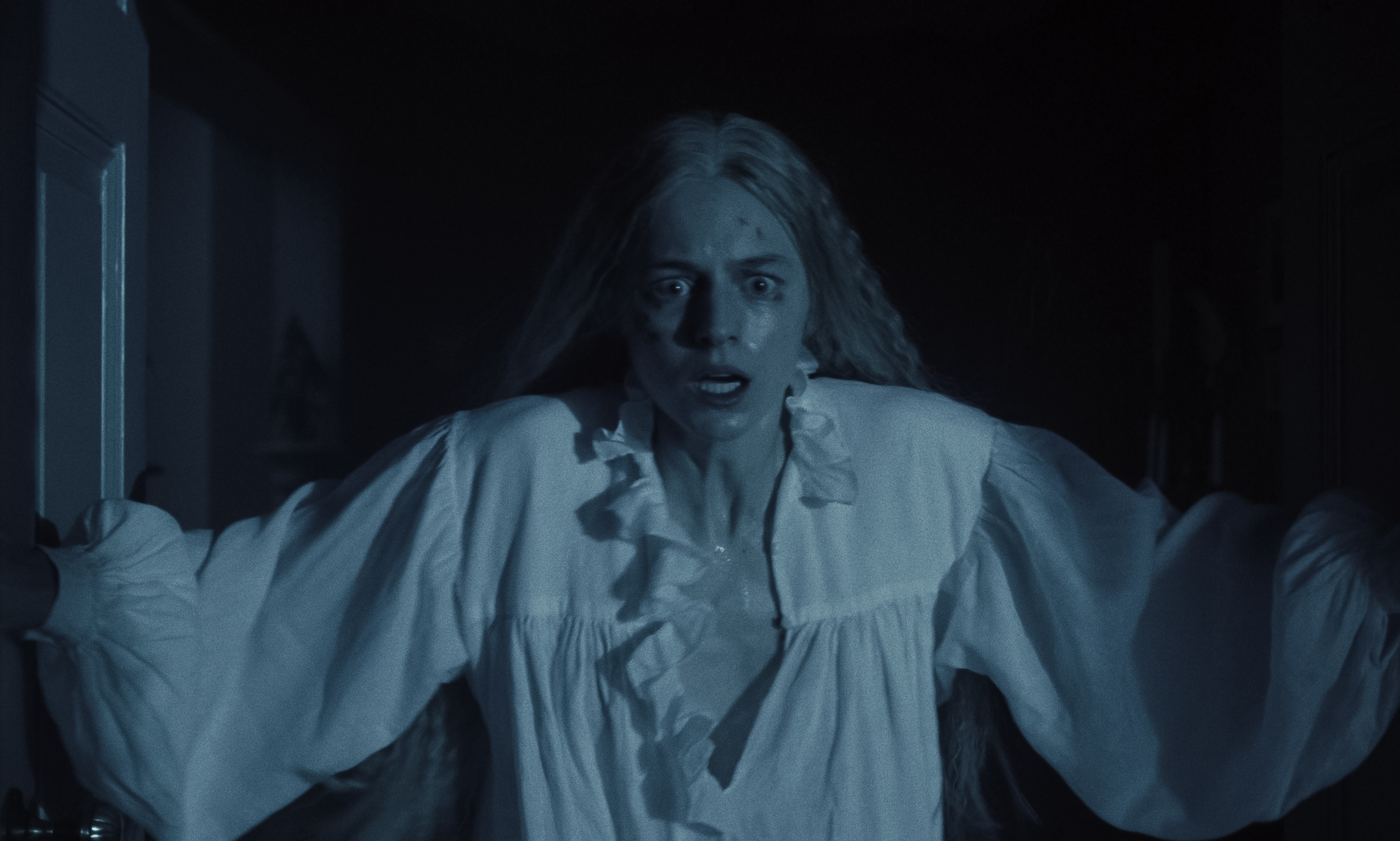

MC: You worked with a few other cast members, including Emma Corrin on the scene when she succumbs to the plague. What was that like?

MGR: Gosh, yes, the rats. They had a caravan on site, so I was on the floor of their caravan saying, ‘Well, you could move like this,’ they’re looking at me standing up, of course then they has to go on the floor of this room and actually have rats on their body.

They’re wearing a night dress and the rats all go and sit on their crotch, the warmest place. So my job as a choreographer was to go in and literally move their body so that the rats would have a pathway to go up them a bit more and not settle there. It was the most bizarre moment on set. But Emma was so stoic about it, didn't flinch.

MC: Did you and Lily have conversations about the film’s themes of shame, repression, and desire, and how that manifests in movement?

MGR: Rob created novellas for each character. I never saw it, but they would've done the work of creating the scaffolding for that character in terms of the narrative. My job was to go in and create the physicality.

When you're working with physical movement, you're already working with emotions. You're working with very deep memories sometimes that can be triggered by movement. So, in a way, our conversation was entirely on the physical plane. There's a way of communicating where you don't need so many words.

Nonetheless, some of the major conversations we had were about the ending. The question of: Is she just this sacrificial maiden? [That is] true of the original version of Nosferatu where the woman is super passive, and she's basically sucked the life out of her, and then she's saved humanity. I had tried that version in rehearsal with Bill [Skarsgaard] where he falls out of shot, as in the original Nosferatu and Rob's original storyboarding. Rob and I were like, “Something’s missing here,’ and I said, ‘Look, at this point, she's had her blood half sucked out of her, so she's nearly dead.’ And we had to work really carefully to modulate her death.

I thought, Why doesn't she float back up into the frame and then bring her down with him? It’s almost like, ’Is she a ghost? Is she alive? Is she dead? Is she on the edge of existence?’ I felt that was a really interesting conclusion to the love that she actually genuinely feels for, not something external to herself, but actually a part of herself. It's a way of accepting herself, and that's what makes the ending so beautiful. It is not just a love story between two entities. It's a love story about herself; she's accepted something in herself.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.