On the 500th anniversary of his death, our series Leonardo da Vinci Revisited brings together scholars from different disciplines to re-examine his work, legacy and myth.

The artist and polymath Leonardo da Vinci was once famously named a “Master of Water” in the records of the Florentine government.

In this role, he explored diverting the river Arno away from Pisa so as to cut access to the city, then Florence’s enemy, from the sea. It was one of a number of jobs he held that were dedicated to controlling water as a way of wielding power.

But his notebooks reveal Leonardo’s wider preoccupations with the power of water. He wanted to understand the ebb and flow of tides, the origins of rivers and oceans and the water cycle, as well as the fearsome effects of water in erosion, floods, rain and storms. Water was a force to be reckoned with — as an idea and as a reality.

If humans could not control water, Leonardo argued, they could nonetheless work with it. Over his lifetime, he was commissioned for a range of projects to manipulate water, most often in canals, as a form of warfare.

When Leonardo wrote down his thoughts about how to depict a biblical deluge, central to his thinking was the destructive force of water: “The swollen waters will sweep round the pool which contains them striking in eddying whirlpools against the different obstacles, and leaping into the air in muddy foam; then, falling back, the beaten water will again be dashed into the air.”

His mindset was biblical but he shared with modern scientists an interest in great destructive forces such as tsunamis.

The beauty of water

For Leonardo, water could also be exquisitely beautiful in its flows, eddies and swirls. His illustrations of moving water were not really observations of a single moment in time though; they captured his thought process.

In the illustration below, of water passing obstacles, he depicted movement in time and space, as well as his conceptualisation of how fluids flow, in a single diagram.

Leonardo was depicting the inherently three-dimensional nature of flowing water, and the idea that turbulent flows consist of a range of co-existing eddies, varying in scale from large to small. This concept was mathematically formalised in 1941 by A.N. Kolmogorov, and is known as the “cascade model of turbulence”.

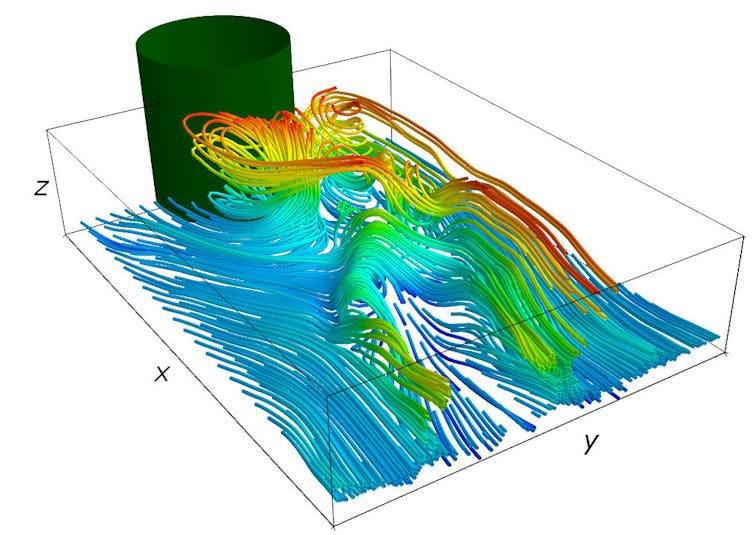

Visualisation of flowing water remains a powerful and essential tool in modern research today. For instance, recent laboratory studies of the three-dimensional flow around islands in coastal ocean regions, have used tiny plastic spheres to observe the fluid motion (known as particle tracking) of the evolving wake downstream of an island.

Describing the complex nature of these wakes, and the vertical up-welling of water in them, is key to understanding how the ecological productivity of these marine systems is maintained.

For Leonardo, flowing water formed parallels with curling hair:

Observe the motion of the surface of the water which resembles that of hair, and has two motions, of which one goes on with the flow of the surface, the other forms the lines of the eddies; thus the water forms eddying whirlpools one part of which are due to the impetus of the principal current and the other to the incidental motion and return flow.

Recently, scientists who study fluid mechanics have employed innovative ways to communicate the results of their experiments through creating a musical representation of the frequency content of the flow. These modern methods share with Leonardo a fascination with the beauty of flowing water.

He may once have held the title “Master of Water” but Leonardo realised that this was one element of the natural world over which he (like others) could only ever exercise limited control, except perhaps, in his art.

Susan Broomhall receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Greg Ivey receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Nicole L. Jones receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.