Inflation, followed by poverty and social inequality are the most pressing issues worrying people around the world right now. Canada has not been immune from the rising cost of living and is still fighting an inflation rate above the two per cent target preferred by the Bank of Canada.

Canada’s inflation rate hit 8.1 per cent in June — the highest it had been in over 40 years. While the rate has dropped slightly afterwards, it was still 6.8 per cent in November, easing to 6.3 per cent in December.

High prices funnel wealth from consumers to owners of large companies and widen the wage gap between CEOs and workers. My research shows consumer prices are higher than they should be. This is even without considering inflation, because of a less studied phenomenon: compound markup.

Less competition than you think

Many economists rely on philosopher Adam Smith’s metaphor of the invisible hand to understand how the market economy works. According to Smith, the invisible hand is the natural force that drives individuals to unknowingly make economic decisions that are best for society.

This economic philosophy maintains the view that competition is ubiquitous in market economies such as North America and western Europe. Competition makes producers undercut other producers’ prices until prices become low enough to just compensate producers for their costs and time.

But, as my research shows, low prices are the exception, rather than the rule. Such news should surprise those who believe in the power of the invisible hand to bring prices down to their lowest possible level.

While still advocating for the principles of free market, including for the invisible hand, Adam Smith was aware that monopolies, which would prevent competition and inflate product prices, could emerge.

Prices much higher than production costs

The concept of markup, which is how many times a price is higher than the cost of production, is not new. Government organizations dedicated to watching the markets already exist to prevent large companies from conspiring against consumers by artificially maintaining high prices.

Economic literature considers only one product at a time or a few slightly differentiated products, such as Adidas and Nike, when measuring markups. Existing theories and estimations ignore that markups multiply when raw materials, ingredients and components travel from one company to another down the production chain.

A company sells an overpriced component to a second company, that second company incorporates it into their yet unfinished product, then sells it at a profit to a third company, and so on. By the time the finished product reaches the consumer, its price has been successively inflated several times.

Take the bread market. My research implies that the price of bread includes substantial profit margins that go to a handful of large corporations. To produce bread, one needs wheat, which is also sold in competitive markets because all wheat is the same and there are many wheat producers.

To produce wheat, however, one needs fertilizers, mostly sold in highly non-competitive markets by large corporations such as Nutrien Ltd., heavy machinery sold by large corporations such as John Deere, pesticides, seeds and other inputs from markets dominated by large corporations.

Tractors need computer chips, steel, aluminium and tires that also come from large corporations. Batteries need rare earth elements, which come from just a few world producers. Each extra step in the production chain adds another layer of profit to the final product’s price — hence, the compound markup.

Consumer price markups are abnormally high

To determine the markups of different industries compared to the costs of production, I compared the market price of products with the “natural” cost of production. This natural cost is neighbourhood-specific and takes into account the average cost of rent, profits and wages for certain areas.

My notion of compound markup compares market prices to this concept of natural cost, because a fair price would equal this cost in a monopoly-free economy.

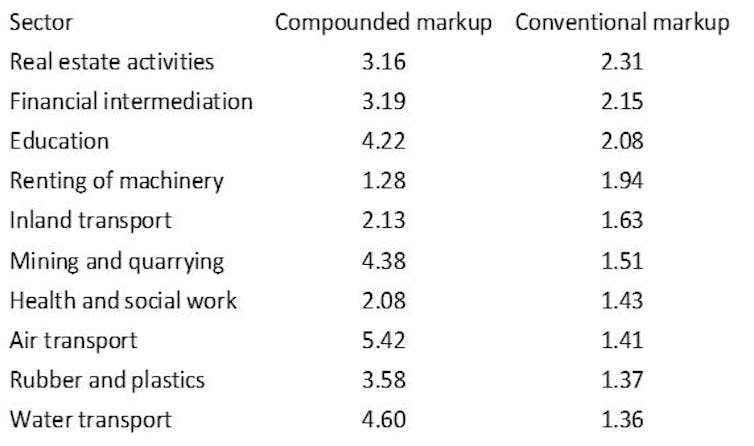

To do this, I measured the overpricing of complex final products such as electronics and transportation services, considering all the overpriced components that the final product incorporates. For data, I used input-output tables, which give flows of sales of intermediate goods from one industry to another. The results of this calculation are the compound markups.

A compound markup of three means the price of the final product is three times greater than the natural cost, considering all the intermediate phases. In contrast, the conventional markup only considers the last phase of production, where the finished good is assembled and sold to a consumer.

These results indicate that prices are, for many of the goods and services we all need, up to five times higher than the natural costs of production. The owners of large corporations make abnormally high profits at the expense of consumers.

Re-thinking market competition

An invisible hand is indeed at work in the supermarket, but it is one that Adam Smith would not recognize. The real invisible hand is there to benefit the producer, not the consumer, contrary to Smith’s belief. Concerned groups have identified fair trade as a goal in international markets for years, but not so much in our daily lives and not in the context of compound pricing.

Governments, consumers and consumer organizations could use research like this to promote more competition in markets, advocate fair trade within a country and re-think income inequality policies.

Large corporations tend to monopolize intermediate markets even more than they do in final goods markets. Because of this, antitrust government agencies like Canada’s Competition Bureau should supervise markets for intermediate goods such as fertilizers, agricultural machinery and rare earth elements — not just the markets for final consumer goods.

Constantin Colonescu does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.