It is literally the biggest semantics story of the week: the informal use of the word "literally" – as a term for emphasis when a statement isn't true – has been included as a definition in the Oxford English Dictionary. Writers have responded, protesting very convincingly that we are breaking up the English language – we are like so many monkeys tossing around a Ming vase, the richest cultural property we possess.

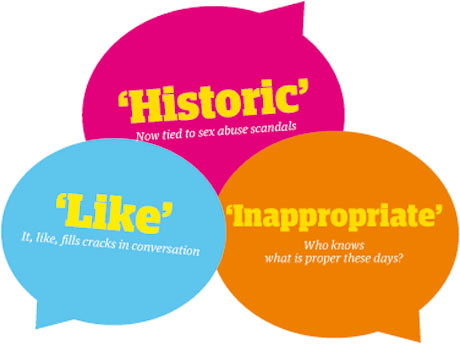

It's immeasurable, but unquestionably there is more written communication nowadays than there ever has been. Consequently, we don't handle language with care any more. Beyond "literally", there is a load of other peeves one encounters in modern communication, verbal and written. Each of them could be taken as another sign of endemic decay. The word whose mishandling I, on my part, feel sorriest for is "historic".

Traditionally, historic meant something grand and noble. For example, Tolstoy's declaration as to why we are all here: "Man lives consciously for himself, but is an unconscious instrument in the attainment of the historic, universal, aims of humanity." Or the following headline from a BBC report on the last, glorious, Test match: Ashes 2013: "Alastair Cook targets historic win in fifth Test at The Oval". It's the kind of word that traditionally gave you a warm glow.

But check out a slew of recent usages and you will find the word "historic" slimed by the poison berry juice of Scotland Yard's Operation Yewtree. Take, for example, the following from the Daily Telegraph of 18 July: "The Jimmy Savile scandal has fuelled hundreds of extra allegations about historic sex attacks, according to the Office for National Statistics." How could such unspeakable offenses against children be tied with Stuart Broad's historic bowling attack at Chester-le-Street, or with Tolstoy's "historic, universal aims of humanity"?

I also object to the suffix "like". It crops up everywhere nowadays in conversation. Rarely, if ever, in written exchanges. It's a kind of vocal lubricant, as in: "I went, like, and told him face to face, like, that, really, like, it's not my responsibility, etc, etc." What's this little linguistic slimeball doing? It fills cracks. In an ugly way.

"Innit?" (equally ugly to the ear) is interesting because English has no handy, and linguistically forceful, equivalent to the French "n'est ce pas?", or the German "nicht wahr?", that is, a kind of questioning tail piece to any declarative sentence that asks for assent, or dissent. The phrase "is that not the case?" is clumsy. I never hear the word "innit" without wishing we had some better way of doing what the Europeans do.

Next, "inappropriate", as in "inappropriate touching" (back, alas, to Savile). It would only work if the word "propriety" meant anything in contemporary speech and there were some agreement as to what "proper" is. It is a moral criterion that belongs in the Republic of Pemberley, the world of Jane Austen. More precise epithets should be found. It is not offensive, but timid.

"Robust" is nowadays a word tossed about promiscuously by those inveterate trashers of language – politicians, government officials, and the spokespeople (shoot that damn word when you see it) of commerce. Too often, companies claim to operate "a robust program". Robust means sweet Fanny Adams here. What, God help one, is a "robust approval program"? A useful word (robust, even) has been annihilated and dragged in to express a kind of "we're gonna tough it out" mentality. A new acronym must be adopted: SOL. Save our literacy.