Hong Kong’s kung fu movies have been popular in the United States since the early 1970s, despite being re-edited, repackaged, badly dubbed and sometimes completely ruined by American distributors.

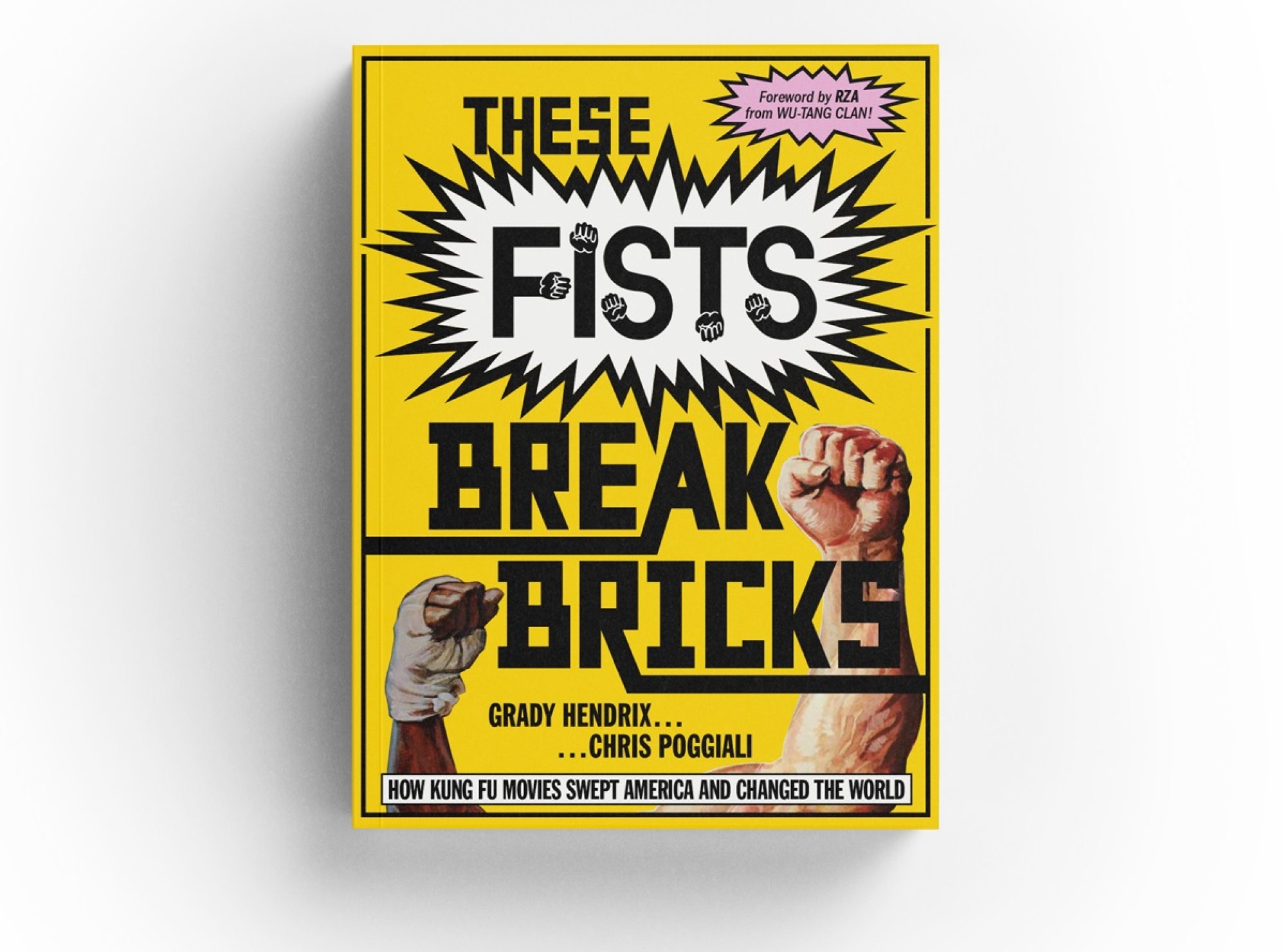

In a new and meticulously researched book, These Fists Break Bricks: How Kung Fu Movies Swept America and Changed the World, authors Grady Hendrix and Chris Poggiali detail the genre’s rise and influence in the US.

The Post secured an advance copy of the book and talked to Hendrix about the time Hong Kong ruled US screens.

The book explains how martial arts were introduced into the US, and how that led to the success of kung fu films. How did that happen?

Judo was brought by immigrants from Japan, and was a huge craze at the beginning of the 20th century. Even President Teddy Roosevelt learned judo. Then World War II happened and the US put the Japanese in internment camps.

When judo came back after the war, it wasn’t as popular – the next big craze was Japanese karate.

The legacies of martial arts film stars Cynthia Rothrock and Nora Miao

People interested in karate were inspired to look for something new, and so kung fu took off in the late 1960s, along with taekwondo. It was the black community which embraced martial arts first, and a lot of black people went into the Chinatowns to see martial arts movies in the cinemas there. So the scene was set for martial arts films to break.

Why did the Hong Kong films of the late 1960s and 1970s resonate with the young black audience?

The movies came out of the anti-colonial protests in Hong Kong. They were “angry young man” movies about young, poor, working-class kids standing up to the system with their bare hands.

That really resonated in America in the early 1970s – you had inner cities where whole neighbourhoods had been written off by politicians and the government, and people were just left to fend for themselves. Young non-white kids felt disenfranchised, and these movies were telling them that just because they were non-white and poor didn’t mean they couldn’t have dignity and self-respect.

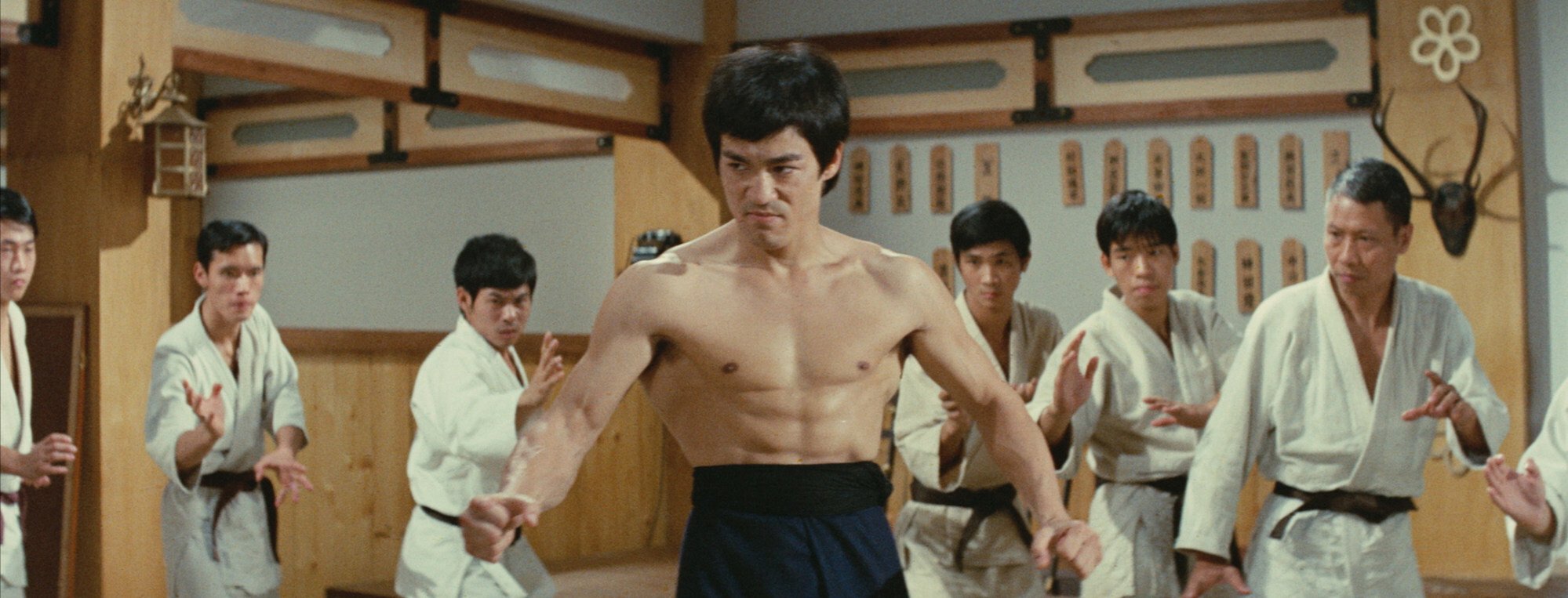

Bruce Lee didn’t introduce martial arts films to America – Five Fingers of Death (also known as King Boxer), and Angela Mao Ying’s Lady Whirlwind (retitled Deep Thrust in the US to trade on the porn hit Deep Throat) – were big hits first …

Bruce Lee was the superstar, but he was not the first. Five Fingers of Death came out in 1973 before Lee’s films hit mainstream cinemas – they had only played cinemas in Chinatowns. Five Fingers of Death was a huge success, even though Warner Brothers only released it to test the market for Enter the Dragon.

After Five Fingers, Angela Mao movies like Deep Thrust were released, and those movies were big successes. Suddenly there was a woman doing action, and that had never happened in the US. Then Lee’s Hong Kong movies got released outside of Chinatowns with English dubbing, and Warners’ Enter the Dragon became a huge hit. Lee became a superstar, and he overshadowed all the others.

The book points out that martial arts films were only mainstream successes for one year, 1973 – they were out of fashion by 1974.

Yes, it was mainstream, and then it wasn’t. It was a bit like hardcore porn in the 1970s. For about a year, hardcore porn was wildly popular – you had people taking limousines to films like Deep Throat, and then that passed.

The same thing happened with kung fu movies. For much of 1973, kung fu movies were mainstream – Angela Mao, Five Fingers of Death, Bruce Lee, these were the movies you had to see. But by the end of the year, the moment had passed.

What was behind the decline?

There were a lot of martial arts distributors picking up crummy movies, and that had an effect. The saying was that as long as it was in focus, it had martial arts in it, and it ran 90 minutes, you could sell it – and I would say it didn’t even have to be in focus for the full 90 minutes!

Also, they mainly screened in urban cinemas that were not in good parts of town, and people were worried about going to them for safety reasons. But when they started appearing on TV in the 1980s, they became successful again, as viewers did not have to go to a bad part of town to see them.

What effect did the death of Bruce Lee have on the martial arts film scene in the US?

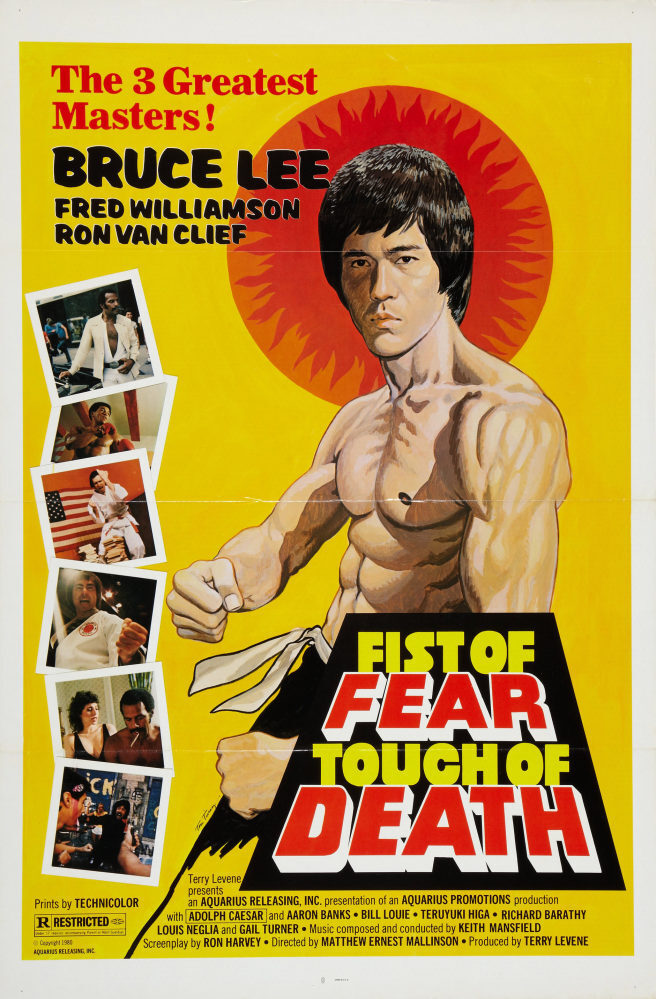

Once Bruce Lee died, everyone wanted to make money from him any way they could. Even if you just had footage of one of his old childhood Cantonese melodramas, that was gold. You could cut that into a movie and present it as Bruce having a dream about his childhood. The next best thing was to get a Bruce Lee imitator, and there were dozens of them. It was a crazy time.

You had people taking footage of Bruce Lee’s funeral, sticking it on the front of an existing movie and releasing it as a film. An 11-year-old boy in New York edited Bruce Lee footage from The Green Hornet TV show into a movie and made millions. People were insatiable, they just wanted more Bruce Lee. The “Bruceploitation” movies are generally pretty terrible – I watched so many for this book, I probably gave myself brain damage!

Did Hong Kong films become insignificant in the US after the success of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon?

Not at all. Before the bubble burst, Hong Kong had developed world-class talent for 40 years, and that talent went on to influence filmmakers everywhere. It’s like Hong Kong created a seed pod that exploded and pollinated the film world.

These Fists Break Bricks: How Kung Fu Movies Swept America and Changed the World is published by Mondo Books in September.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved genre. Read our comprehensive explainer here.

Want more articles like this? Follow SCMP Film on Facebook