In January 2010, eight months into his job as mayor, Julián Castro delivered his vision for San Antonio to the city’s business and political elites. Inside a packed ballroom at the Grand Hyatt Hotel downtown, Castro vowed to create thousands of new jobs, invest in renewable energy and focus on education and boosting student achievement.

Perhaps Castro’s greatest promise, however, centered on the physical transformation of the city. During his first state-of-the-city speech, Castro heralded a grand urban redevelopment project that would, in his words, make the 2010s the “decade of San Antonio.”

On the streets just outside the hotel, the challenge was obvious. While the city’s tourism trade banked off the nearby convention center, the River Walk and Alamo Plaza, the rest of downtown San Antonio was pockmarked with blocks of empty storefronts and abandoned office space, thanks largely to decades of neglect and suburban sprawl. Hardly anybody lived there. Castro wanted to reverse those trends by goosing development downtown — stores, restaurants, parks, apartments — in order to lure people back to San Antonio’s core.

The project, which Castro later remarketed as the “decade of downtown, ” worked. In fact, it worked so well that last year officials pumped the brakes on key building incentives created under Castro, all over fears that the wave of publicly subsidized development would exacerbate San Antonio’s affordable housing crisis and displace poor people.

Those incentives gave hundreds of millions of dollars in tax breaks and fee waivers to developers, who primarily built luxury condos and apartments in one of the most economically segregated cities in the country. With a population boom on the horizon and rising housing costs that continue to outpace wage growth, San Antonio is now bracing for a housing crunch. In December, city leaders tweaked the Castro-era development incentives in an attempt to tackle gentrification.

Castro himself began to express similar concerns on his way out of office in 2014, as the Obama administration tapped him to lead the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, where he pushed fair housing policies for the next two and a half years. In his run for the Democratic nomination for president, Castro says he drew from that experience at HUD to propose one of the most expansive housing affordability plans of any candidate in the race.

Still, some advocates for affordable housing say Castro’s vision for redevelopment in San Antonio revealed a blind spot for the issue during most of his time as mayor, long before he began to push much bolder proposals in his run for president — and long after the concrete was cast in his hometown.

–

Castro’s rise, and that of his twin brother, U.S. Representative Joaquin Castro, was almost preordained — a continuation of a legacy started by their mother, a Chicana activist who fought for fair representation for the city’s Mexican American majority. In 1971, she ran an unsuccessful campaign for city council as part of a broader agenda to seize power from wealthy Anglos who controlled the city. Three decades later, in 2001, Castro became San Antonio’s youngest-ever city council member at age 26. Early in his political career he fostered a reputation as a voice for the people, a “protector of the grassroots” willing to stand up to big developers, no matter the personal cost.

This is the version of himself he presents on the campaign trail today. At a packed Austin rally two days after his breakout performance in the first Democratic presidential debate, one that made him the leading Texan in the race, Castro capped his speech talking about the first time he was tested as a politician.

One of Castro’s first critical votes as a council member centered on a golf course developers wanted to build over the Edwards Aquifer’s environmentally sensitive recharge zone, where the city’s main source of drinking water is replenished with each rainfall. Castro sided with community groups that opposed the land deal and city tax breaks for the project, but there was a catch: The developers were a client of the law firm where Castro worked, which in turn asked him to recuse himself from the vote.

So Castro quit his job and voted against the deal. As a result, he told the crowd, his home went into foreclosure, he fell behind on car payments and eventually started fielding calls from bill collectors. “Before I ever went into politics, I worried that I’d have to change who I was to succeed,” he said. “You hear that politics can be dirty or corrupting, that you have to play this game with people who usually get their way and special interests that donate a lot. I was proud that when that first test came when I was 27 years old, that I stood up and did the right thing for the people I represented.”

For some in San Antonio, the golf course saga provided a very different lesson about Castro. Two years later, in 2004, the deal resurfaced at city council, albeit with stronger environmental protections in exchange for a bigger tax break. Castro, prepping for his first and ultimately unsuccessful run for mayor against a business-backed opponent, signaled his willingness to work with developers by coming around on the project.

Castro framed his newfound support as a compromise that would “both grow our economy and protect the environment.” Leftists have since criticized the episode as a sign of Castro’s larger “politically motivated drift toward neoliberal politics,” a la Obama. Despite multiple requests over several weeks, Castro’s campaign wouldn’t make him available for an interview to discuss his time at city hall.

“At first, when he voted with the community, everybody was excited that this was the progressive who was going to change things, but then he flipped,” Graciela Sanchez, a prominent activist who opposed the golf course, said in an interview with the Observer. “Like most ambitious political leaders, it’s not like he didn’t care about the community or wasn’t interested in the struggle. He just became very calculated,” Sanchez said. “He wanted to be mayor.”

–

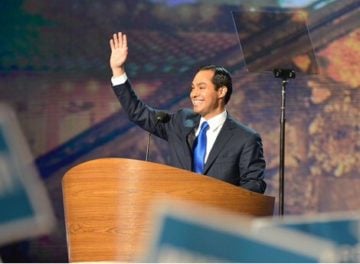

While Castro has long been a celebrity in San Antonio, he was already marginally famous outside the city even before he won his first mayor’s race in 2009. Glowing profiles in both state and national news outlets began calling him a symbol of generational change. His fame grew after the Democratic National Convention picked him to deliver the 2012 keynote address, the first ever by a Latino politician.

People who followed Castro’s political career in San Antonio aren’t surprised he’s now standing out from the throng of Democrats running for president. As mayor, he seemed determined to make his mark on the city with big, splashy ideas that grabbed national headlines, like a $30 million sales tax increase to fund pre-K for poor kids throughout the city.

Still, the “decade of downtown” may ultimately be Castro’s most visible and lasting legacy in San Antonio. Pockets in and around the city center have fundamentally changed since the start of the decade — from the area surrounding the bougie Pearl complex north of downtown, to the new tech companies helping shape the Houston Street corridor, to the townhouses and restaurants that have exploded onto Southtown, once the bohemian epicenter of the city’s arts community. According to the San Antonio Express-News, building incentives created under Castro brought $4.4 billion in investment to San Antonio’s urban core since 2012. Community advocates are now anxiously waiting to see how that wave hits working-class neighborhoods on the periphery of downtown.

Castro himself began to grapple with the unintended consequences of this sea change on his way out of city hall in 2014, when urban redevelopment displaced hundreds of poor and working-class people living in a trailer park on the edge of downtown. Researchers who studied the displacement say three residents died after they were forced to move — two elderly women and a middle-aged man who took his own life.

In one of his final acts as mayor, Castro voted against zoning changes that ushered the residents out of their homes and created a city task force to combat gentrification. Years later, on a swing through his hometown as HUD secretary, Castro urged San Antonio to address housing affordability as home prices and monthly rents continued to rise. “I’m convinced that if San Antonio does not take bolder steps now to enhance housing affordability, then in a few years this … will give rise to a decade of displacement.”

Christine Drennon, an urban studies professor at Trinity University, sat on Castro’s gentrification task force. She says the city has yet to craft an affordable housing plan that can counterbalance the hundreds of millions of dollars in city incentives developers were given to build housing that most San Antonians can’t afford.

“In Secretary Castro’s defense, he came out years later and said we need to stop and think about what we’re doing with all these incentives,” Drennon said. “It was a little late. By that point, he’d basically moved on to bigger and better things.”