In recent years, countless scientific studies — and media reports — have touted the benefits of nature for improved well-being. But as it turns out, there’s more to the scientific literature than the headlines would suggest.

In a paper published Friday in the journal Science Advances, researchers reviewed hundreds of studies on the “cultural ecosystem services” that nature provides for wellbeing, which is a fancy way of referring to the non-tangible — i.e., non-economic — impacts nature has on humans

Their meta-review reveals far more complex links between nature and wellbeing than the well-trodden narratives around nature and better mental health. By looking more closely at the existing scientific literature, the researchers suggest we can craft better policies that take into account how different groups of people interact with the environment and the intangible benefits they get from spending time in nature.

“In this paper, we are not simply identifying the different [cultural ecosystem services], but we go deeper to find how they are linked to different aspects of human wellbeing,” Alexandros Gasparatos tells Inverse. Gasparatos is a co-author on the paper and an associate professor of sustainability science at the Institute for Future Initiatives (IFI), University of Tokyo.

How they did it — In their review, the researchers assessed more than 300 scientific papers to draw certain conclusions about nature’s cultural ecosystem services and their impact on human wellbeing.

Cultural ecosystem services refer to the “non-material and often intangible contributions of nature to humans,” Gasparatos explains.

These intangible contributions might include recreation and leisure, accumulating knowledge, spiritual fulfillment, community building, finding a “sense of place” in the outdoors, and “aesthetic experiences” (so yes, taking selfies in a scenic forest for the ‘gram would probably count). It’s a way of looking at nature beyond the material and economic benefits that we extract from it.

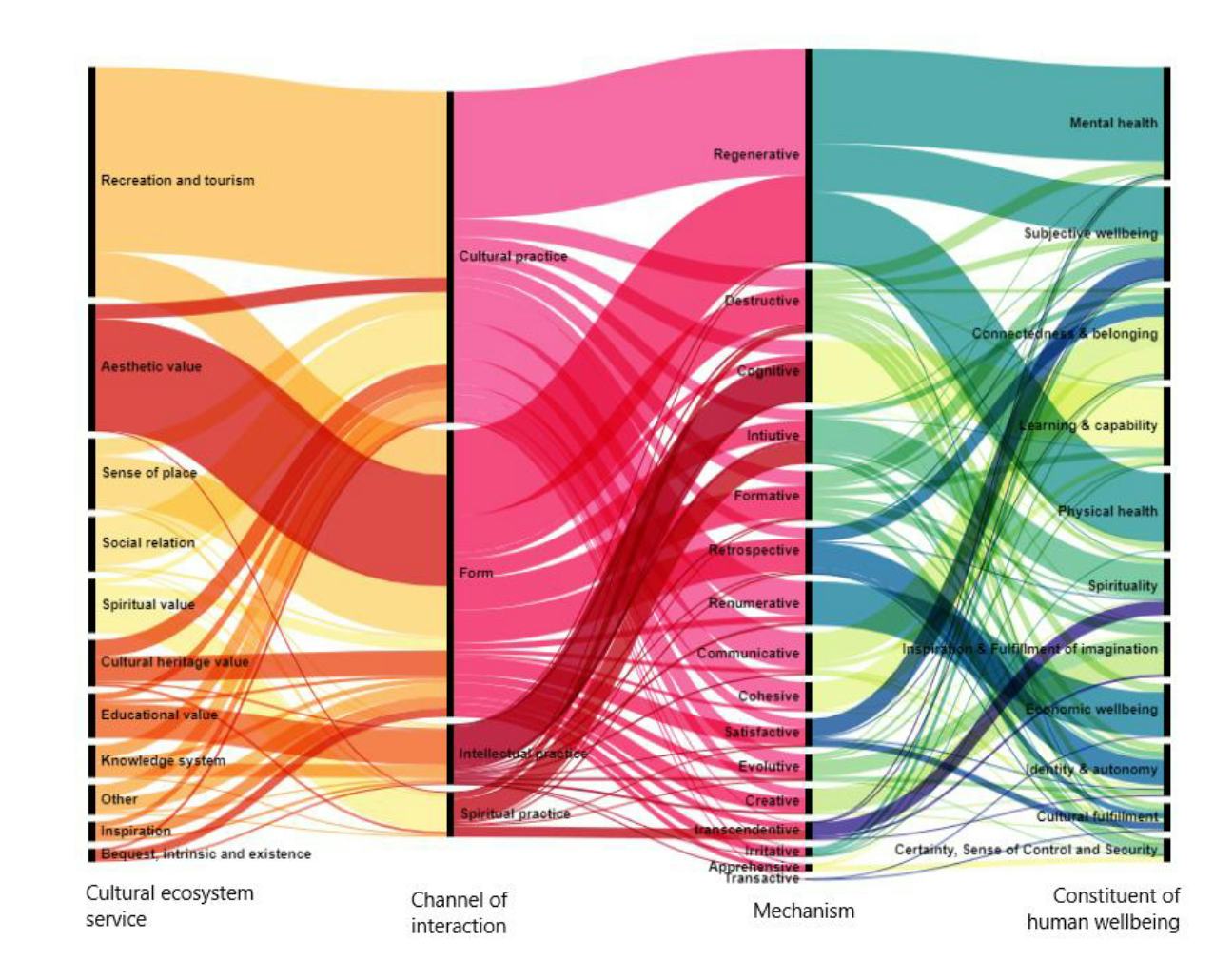

What they found — After studying this vast body of scientific literature, the researchers concluded there are more than 200 “unique linkages” or pathways between cultural and ecosystem services and wellbeing.

The scientists were then able to narrow down these linkages to 68 pathways. Out of the 68 pathways, 45 positively impacted and 23 negatively impacted human well-being.

It might seem surprising that nature could harm well-being, but if you’ve ever been grossed out by a smelly plant or been scared walking alone through a spooky forest, then you’ve experienced one of those negative interactions. Very few studies have systematically analyzed the negative links between nature’s cultural ecosystem services and wellbeing.

Through further analysis, the scientists found there were four different ways people typically interacted with nature. These include:

- Cultural practices — Opportunities for creating, exercising, and gathering natural products

- Intellectual practices — Gaining new knowledge

- Spiritual practices — Religious activities that take place through nature

- Form — Engaging with nature through physical and tangible actions

The scientists also categorized these interactions by the “mechanism” or nature of the experience. Let’s say that spending time in nature inspires you to draw or paint — that would be a “creative” experience. Whereas someone who looks up at a tall mountain and experiences an overwhelmingly powerful force would be experiencing a “transcendentive” experience, defined in the paper as “the benefits that lie beyond the ordinary experiences and the regular physical realm, more often associated with religious or spiritual values via interaction with nature.”

In total, the researchers identified 16 different types of mechanisms spanning the gamut of human encounters with nature. The complex nature of these interactions astonished the researchers.

“The mechanisms and pathways are many more than we initially thought,” Gasparatos says.

Some of these pathways have “tradeoffs” with each other — and not always in good ways. A good example is the tradeoff between recreation and leisure — i.e., tourism — and spiritual practices. Tourists might enjoy going for a weekend hike in the wilderness, but they might also be trampling on sacred land traditionally used for Indigenous spiritual activities. Tourism may also lead to the development of certain areas, leading to environmental degradation and the loss of Indigenous knowledge related to the local ecosystem.

Finally, Gasaparatos says the existing research suggests that the “inner” connections to nature, like the sense of community belonging we get from being with others in the outdoors or the knowledge we glean about the natural world, have a stronger impact on human wellbeing than the monetary benefits nature provides for economic output.

Why it matters — The new paper establishes that humans interact with nature in complex ways — perhaps more than we previously understood — but what’s the bigger impact?

First: the study shows how we’ve often overlooked certain connections to nature — like its importance in cultural practices or Indigenous knowledge — in popular discourse while focusing mostly on the obvious mental health benefits of spending time outdoors.

Gasparatos says the selective focus likely stems from the fact “that health is much more prominent in the public debate than other aspects such as sense of place or culture.”

Further, studies that do focus on the cultural and intellectual connections to nature are usually focused on specific communities or “ethnographies,” which has made them harder to quantitatively assess and communicate to a broader audience.

Second: Gasparatos and his fellow researchers didn’t find these connections in nature themselves, but they were able to draw them out from the existing scientific literature in a way that didn’t exist before.

“What we do here is to systematize the literature in a very novel way that allows us somehow to compare these benefits between studies,” Gasaparatos explains.

Finally, this research could improve environmental design and ecosystem management by helping people in positions of power understand these complex linkages between nature and human wellbeing.

For example, if a city official wants to install green spaces to improve physical and mental well-being for urban residents, they can look at the specific “pathways” connected to this goal and design green spaces accordingly — like implementing landscape designs that have a calming effect to reduce stress or natural elements that appeal to the senses.

What’s next — Still, there are significant gaps on the nature and well-being connection that existing scientific literature has yet to address, according to the paper.

“One of the knowledge gaps we identified is that the existing literature mainly focuses on the individual well-being, and lacks focus on collective — community — wellbeing,” Gasparatos says.

To fill that gap, the research team intends to conduct a “multi-scale well-being assessment” based on the findings of this recent paper. Their future research will assess the impacts on well-being on residents in different environments, ranging from dense Tokyo to a “rapidly urbanizing” area in Central Vietnam where coastal ecosystems are being transformed for tourism.

The project will serve as “a logical follow-up to test how some of identified pathways and mechanisms unfold in reality and intersect with human wellbeing,” Gasparatos concludes.