Achieving immortality is something that has driven human beings throughout much of their history. Many peculiar legends and fables have been told about the search for the elixirs of life. Medieval alchemists worked tirelessly to find the formula for the philosopher’s stone, which granted rejuvenating powers. Another well-known story is the travels of Juan Ponce de León, who, while conquering the New World, searched for the mysterious fountain of youth.

But to this day no one has succeeded in discovering the keys to eternal life. There is, however, one exception – a creature no more than four millimetres in size Turritopsis dohrnii, also known as “the immortal jellyfish”.

Biological immortality, within reach of a jellyfish

Unlike the vast majority of living organisms, Turritopsis dohrnii is capable of rejuvenation and biological immortality. This challenges our perception of ageing, but how does it do so?

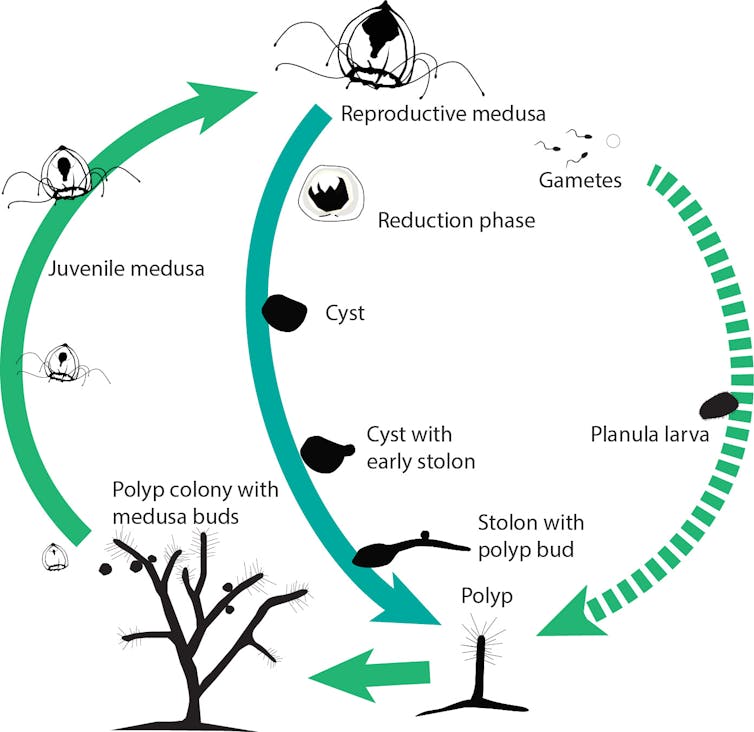

Let’s start by understanding the generic life cycle of a “mortal jellyfish”. It reproduces sexually: the male’s sperm fertilises the female’s eggs and the zygote is formed. The zygote grows as a larva and drifts until it attaches itself to the seabed. Once settled, it grows into a polyp and, when ready, it reproduces asexually. To do this, it releases tiny jellyfish from its own body, which then grow to the adult stage and reproduce, before dying.

The immortal jellyfish, Turritopsis dohrnii, also follows this cycle, but after reproducing it does not always die: it can choose an alternative path and reverse its life cycle. Along the path, its jellyfish body shrinks to form something like a sphere, called a “cysto”. This drifts until it sticks to the bottom, and then generates a new polyp, which in turn gives rise to new jellyfish, thus entering the cycle again.

This process can occur endlessly and allows the jellyfish to escape death.

Deciphering the immortal jellyfish genome

The keys to the immortality of Turritopsis dohrnii are written in its DNA, but discovering them has been no easy task.

Our research team led by Carlos López Otín at the University of Oviedo has contributed to deciphering the genome of this immortal jellyfish. The results have been published in the journal PNAS. This was done by reading letter-by-letter and writing out gene-by-gene all its DNA as if it were a huge instruction book.

This huge book contains all the information needed for cells to carry out their vital functions. As a result, several genomic clues have been defined that contribute to understanding the extraordinary longevity of the immortal jellyfish.

Using various bioinformatics tools and comparative genomics (the comparison of the genetic book between species), it has been discovered that Turritopsis dohrnii possesses a number of genetic variations that contribute to its biological plasticity and longevity.

The genes found are associated with different keys to ageing such as DNA repair and replication, renewal of the stem cell population, cell-to-cell communication and reduction of the oxidative cellular environment that damages cells, as well as the maintenance of telomeres (chromosome ends).

All these processes are associated with longevity and healthy ageing in humans.

In addition, by studying each stage of their rejuvenation in detail, a series of changes in gene expression have been identified that are necessary for the cells to transform, through a process known as dedifferentiation. This allows the Turritopsis dohrnii to effectively reset its own biological clock.

All these mechanisms act synergistically as a whole, thus orchestrating the process to ensure the successful rejuvenation of the immortal jellyfish.

The true secret of immortality

If Juan Ponce de León had known the secrets kept by Turritopsis dohrnii during his search for the fountain of youth, he would have been left parched. And the alchemists would not have found the philosopher’s stone they so longed for. That’s because, unfortunately, it wouldn’t be possible for a human body to replicate what the jellyfish does. Perhaps the only way to find such a fountain or stone is to realise that there is no life without death. That every system, like humanity or our own body, needs the death of some of its parts to remain in balance and survive.

From the fascinating exploits of Turritopsis dohrnii we have learned the keys and limits of cellular plasticity, and from this knowledge we hope to find better answers to the many ageing-related diseases that trouble us today.

Nonetheless, the dream of biological immortality for humans remains just that: a dream. Humans have at least discovered how to be immortal in another way – by making their contribution to history through art and knowledge.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.