Pressure on the UK government to confirm its plans for the controversial HS2 high-speed rail project is growing as the Conservative party prepares for its annual conference.

Much of the country is keen to hear about the fate of HS2. But since the conference is being held in Manchester, one of the northern cities set to benefit from HS2 if it goes ahead, this is intensifying calls for a decision.

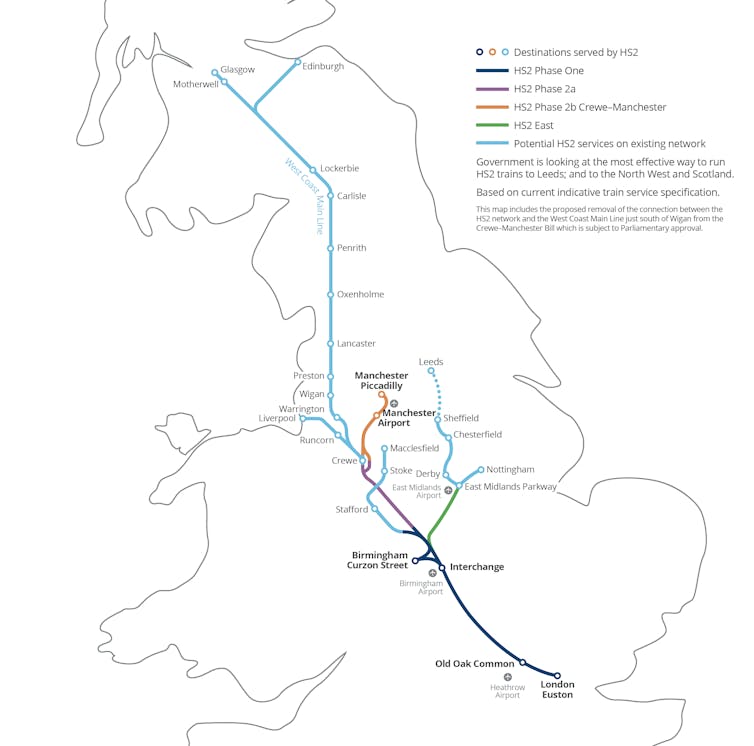

The UK’s prime minister, Rishi Sunak, and chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, are weighing up the rising costs versus the benefits of HS2. In particular, they must decide on whether the high-speed rail line should continue beyond Birmingham. The eastern link to Leeds has already been cancelled, and the leg to the East Midlands is yet to be confirmed.

Now, rising costs mean HS2 could also terminate at Old Oak Common in West London, rather than its original Euston terminus in central London. This would turn a high-speed connection between major English cities into the “Acton to Aston line”.

The idea behind HS2 was to generate prosperity and opportunity for areas of the country suffering disadvantage. But do high-speed trains represent the most effective way of doing this?

Although Sunak continues to voice his commitment to levelling up and “spreading opportunity around the country”, UK high-speed rail links do not seem to offer value for money in the current environment of rising costs.

The rising costs of HS2

Over the decade since 2013, when construction commenced on the first phase of HS2, it has come under regular scrutiny because of rising costs. Work on the 140-mile London to Birmingham line, originally estimated at £16 billion, is now budgeted at £44.6 billion.

At £300 million per mile, this is considerably higher than typical costs for constructing high-speed rail in Europe, according to analysis by The Times. The cheapest recent project, Spain’s Madrid to Galicia line, cost £19 million a mile and the highest, Stuttgart to Munich in Germany, came in at less than a quarter of HS2 at £70 million a mile.

Trains operating well in excess of 300kmh (186mph) are running across the world – and research shows that being able to transport people and goods by high-speed train confers advantages to local economies. Stronger transport links encourage the development of local business ecosystems that suppliers of specialised goods and services, as well as labour, can reach more easily.

The Department for Transport (DfT) argued the case for disadvantaged communities being close to trains with a maximum speed of 250mph in a 2015 report. It outlined the case for attracting knowledge-based firms to these areas, because they had created jobs at three times the rate of other sectors since 1984. In a report produced the same year, the Economic Affairs Committee spoke of using rail connections to integrate UK cities that each “possess their own specialism”, arguing this would increase productivity.

But even with these acknowledgements of the potential competitive advantage, Britain’s progress in developing a high-speed network has so far been limited to the HS1 link between St Pancras and the Channel Tunnel. Southeastern Rail operates HS1, which was opened in two sections in 2003 and 2007. It has a maximum speed of just over 185mph (for international services) and cost £6.84 billion to build (£51 million per mile). It was completed on time and under budget.

HS1 is estimated to delivers an annual economic benefit of £427 million. Among many factors, this is based on the cumulative effect of reduced journey times, as well as productivity gains from “agglomeration”, which is when many businesses are attracted to one area – think Silicon Valley. They benefit from cost savings by being close to each other and attracting an ecosystem of useful services and workers.

The vision for HS2

After the relative success of HS1, Labour’s transport secretary Lord Adonis announced a new plan to build a high-speed rail link between London Euston and Birmingham’s Curzon Street on March 11 2010. He said high-speed lines would be built northwards to Manchester, Leeds, the East Midlands and Newcastle, with connectivity to the existing lines enabling through services to Scotland. These lines, Adonis suggested, would unite England and Scotland, north and south, and lead to greater “sharing wealth and opportunity, pioneering a fundamentally better Britain”.

With an estimated cost of £37.5 billion in 2013 (at 2009 prices), HS2 represented considerable public investment to achieve what’s now commonly referred to as “levelling up”. However, even at the outset of this project, the theory that high-speed trains significantly reducing journey times would result in the sort of economic and social benefit claimed by Adonis were questioned. In 2013, former business secretary Lord Mandelson warned it might prove to be an “expensive mistake”.

Labour lost the general election in May 2010 and was replaced by a Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition that was committed to cutting public expenditure. Government support for HS2 to achieve wealth creation outside the capital continued, however. The David Cameron-led government supposedly saw HS2 as a “counterbalance” to extreme “local austerity”. A parliamentary bill was passed in 2013 to start construction.

Unachievable

But any economic benefits of HS2 that were justified at the outset have diminished over the last 10 years, to the point that they are now considered negligible. According to leaked analysis carried out by the DfT last year, increasing costs means HS2 will “deliver just 90 pence in economic benefit for every £1 it costs”.

Critics of HS2 now consider it to be abnormally expensive and the government’s authority on major projects, the Infrastructure and Projects Authority, says the first two phases of HS2 (London to Birmingham and Birmingham to Crewe) are “unachievable” due to potentially “unresolvable” issues with the schedule, budget and delivery of benefits, among other problems.

Investment in infrastructure is urgently required in urban areas in the north of England to ensure it benefits from east-west connectivity through reliable and efficient train services. But these links could be built faster and cheaper than HS2.

And had the money budgeted for this eye-wateringly expensive project been spent on regeneration, housing and stimulating opportunity for investment in innovation and job creation over the last decade, genuine levelling up in the north of England might already be well under way.

Steven McCabe does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.