One Sunday 20 years ago, Rosman Wai Chui-chi had agreed to spend the afternoon babysitting her niece. She decided to take her to the first resettlement housing block built in post-war Hong Kong.

It might appear an odd destination, but it wasn’t for Wai, an architect who worked for the city’s Housing Department for more than 30 years, and who now lectures on architectural conservation at the University of Hong Kong.

She thought she knew everything there was to know about public housing in Hong Kong. But children have a way of putting things in a new light, and as her niece peppered her with questions, Wai realised her knowledge was not quite as deep as she had assumed.

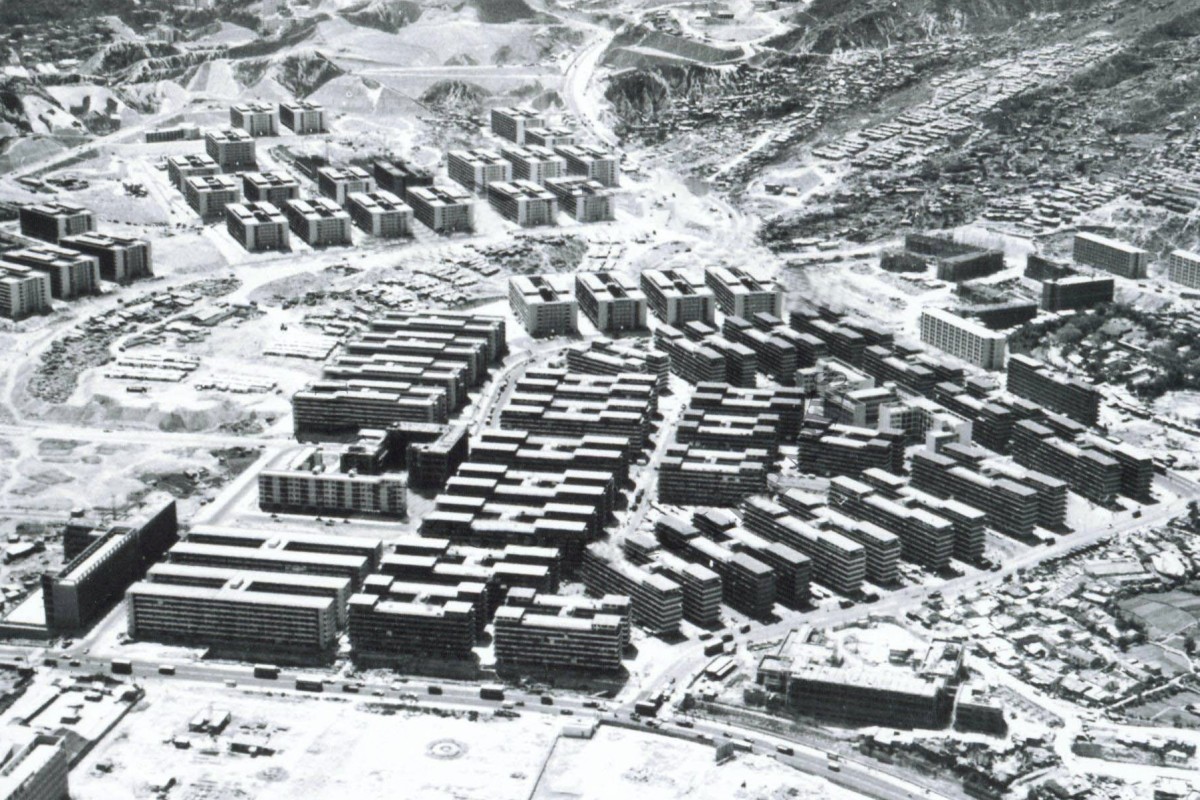

More than 50 per cent of Hongkongers live in some form of public housing, and a vast programme to build mass-housing estates is said to have been started in response to a fire on Christmas Day, 1953, that swept through shanty homes in Shek Kip Mei, Kowloon, and left 50,000 squatters homeless.

Was this really the case – or just a convenient myth? And how did Hong Kong’s earliest public housing come to look the way it did?

Wai set out to find the answers. The result is a book, Design DNA of Mark I: Hong Kong’s Public Housing Prototype, a thoroughly researched and brightly written analysis of the housing blocks which sprouted over the hills of Kowloon in the 1950s, and laid the groundwork for generations of public housing to come.

There were a lot of things to do after the war - Rosman Wai, architect and author

Writing the book wasn’t easy. “The architectural provenance of Hong Kong’s public housing remains a much under-researched area,” Wai notes in her introduction. That seems astonishing, given the ubiquity of public housing in the city.

“Still today, people think that public housing is not architecture,” says Wai. “They think it’s just shelter. Also, few architects like to do research. It isn’t their cup of tea. And in Hong Kong, archiving is quite behind [the times]. There are people who take care of that, but their power and staff are so small.”

Wai spent the next several years diving into archives in Hong Kong and London. She identified who was responsible for the design of what were known as Mark I resettlement blocks – G.P. Norton, the then acting chief architect for the Public Works Department – but the exact origins of the distinctive blocks was a mystery.

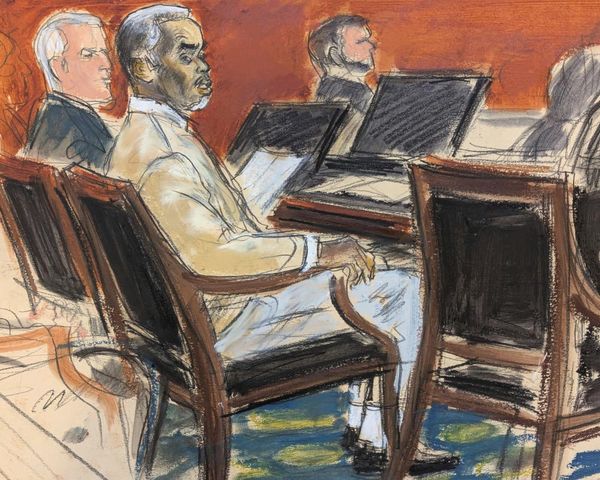

They were unlike anything Hong Kong had seen before. Shaped like an H, the buildings consisted of two linked sections, each of six storeys, with 64 flats on each floor, accessed by long balconies. Each flat measured 120 square feet, and bathrooms were communal. There were no kitchens: cooking was done on the balconies. The ground floors housed restaurants and light industrial workshops, while the rooftops were used for school and recreation.

From her archival research, and interviews with Michael Wright, Hong Kong’s former chief architect and a colleague of Norton, Wai was able to determine that the design of the Mark I was a hybrid of Hong Kong’s existing tong lau – tenements – and the terraced housing built for working-class families in Britain after World War II.

Wai doesn’t stop there. Her book is a snapshot of Hong Kong’s built environment in the 1950s, with detailed drawings and photographs of tong lau, composite buildings (mixed-use blocks designed like giant shophouses, such as Chungking Mansions in Tsim Sha Tsui), civil servant housing, squatter huts and all the other spaces people were living in at the time. It’s also an analysis of the social and political conditions that led to Hong Kong’s vast public housing programme.

“There were a lot of things to do after the war,” she says. Architects such as Wright and Norton were imbued with a sense that things couldn’t be done as they had before. Wright told her that, while he was being held in a Japanese internment camp during the war, he chatted with other architects and engineers about the failures of Hong Kong’s housing stock, particularly the lack of ventilation in tenement buildings.

One of Wai’s revelations is that Hong Kong has always suffered from a shortage of good-quality housing. “In the 1880s it was a problem because the population was growing,” she says. Cubicle homes were already common back then, and the government was worried that there was no fresh air or light in many subdivided flats, but weak regulation meant poor-quality housing was always a scourge.

The Mark I design for public housing addressed the ventilation problem by providing a “pigeon hole” opening in the wall between flats, allowing air to circulate. It was the first time in Hong Kong’s history that the government was building housing for its people, and the first time it was taking a proactive approach to ensure quality of life.

Now that she has published Design DNA of Mark I : Hong Kong Public Housing Prototype, Wai has her sights on the rest of Hong Kong’s public housing. Mark I estates such as the original Shek Kip Mei Estate and the Chai Wan Resettlement Estate were followed by estates featuring a range of block designs, including Trident and Cruciform – whose names reflected their shape – and Harmony, which consisted of four distinct blocks attached to a central core.

Even in the case of these more recent types, there is a lack of documentation about the origin of their design.

“That’s why I want to continue my work, because otherwise the information will be lost,” she says.

Today, there is no longer a standard block type for public housing in Hong Kong. Instead, each new housing estate is made up of modular units that can be arranged according to the specific needs of each site.

“Let’s say there is a busy road, you can put it so that the toilet is against the road, not the bedroom and living room,” says Wai. “If you go to a new public housing estate you’ll find it is even better than private housing. I always tell people that, but they don’t believe me because they have this old stereotype of public housing in their minds.”

She hopes her work can change that perception, because public housing isn’t just another type of dwelling in Hong Kong – it’s part of the city’s DNA.