The circumstances of Jean Seberg’s death 40 years ago in late August 1979 were squalid and pathetic. The American star’s body lay decomposing in a car on a street in Paris for 10 days before the French police discovered it. There was a bottle of barbiturates and a suicide note beside the corpse. As the press reported, her body had “baked in the sun” and the odour was “unimaginably foul”. This was the actress who, at the start of her career, was described as “so unimaginably fresh” by her colleagues.

Paris was the city with which Seberg was most closely associated. Every film lover remembers her in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960) in her white New York Herald Tribune T-shirt, selling newspapers and gallivanting around the streets with her co-star, Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Seberg had one of the strangest and most contradictory careers of any Hollywood star during the postwar years.

“She was so misunderstood. It’s not like you need to hero-worship a celebrity, they are just people you want to look at. The fact that people stared at her and fixated on things that were not real, projections: that really ultimately destroyed her,” Kristen Stewart, who plays her in the new film, Seberg, commented of the ill-fated actress in a Vanity Fair interview. As an actor who has worked on both big Hollywood productions like Twilight and in independent French arthouse features, Stewart seems perfectly qualified to play her.

Seberg, out in UK cinemas this Friday, isn’t a straight biopic. Its focus is its subject’s deadly entanglement with the FBI. Days after her suicide, the FBI admitted that its agents had plotted to ruin her reputation as part of their counter-intelligence programme, Cointelpro, authorised by FBI founder, J Edgar Hoover himself. Seberg’s crime, in Hoover’s eyes, was her involvement in political causes and her support of the Black Panther Party. In particular, they were suspicious of her close links with Black Power leader, Hakim Jamal (played in the film by Anthony Mackie).

In 1970, the FBI planted the false rumour that Seberg was pregnant by a Black Panther Party member in order to “cause her embarrassment” and “cheapen her image” with the American public. Their plan worked. It was dispiriting but inevitable that some gossip columnists followed the false leads that the FBI dangled in front of them. From the FBI’s point of view, she was involved in radical politics, had contributed financially to the Black Panthers and was therefore fair game. The story was picked up by gossip columnist, Joyce Haber, who referred obliquely to it in the Los Angeles Times. Newsweek also wrote about it and named Seberg.

“Under the ruthless gaze of the FBI, the threads of Jean’s life come apart,” Benedict Andrews, the director of Seberg, pointed out. The assault on her reputation set in motion the events that led to her death a decade later. At the time of the leak, Seberg had indeed been pregnant. In the wake of reading the false stories about herself, she went into labour. Her baby was born prematurely and died a few days later.

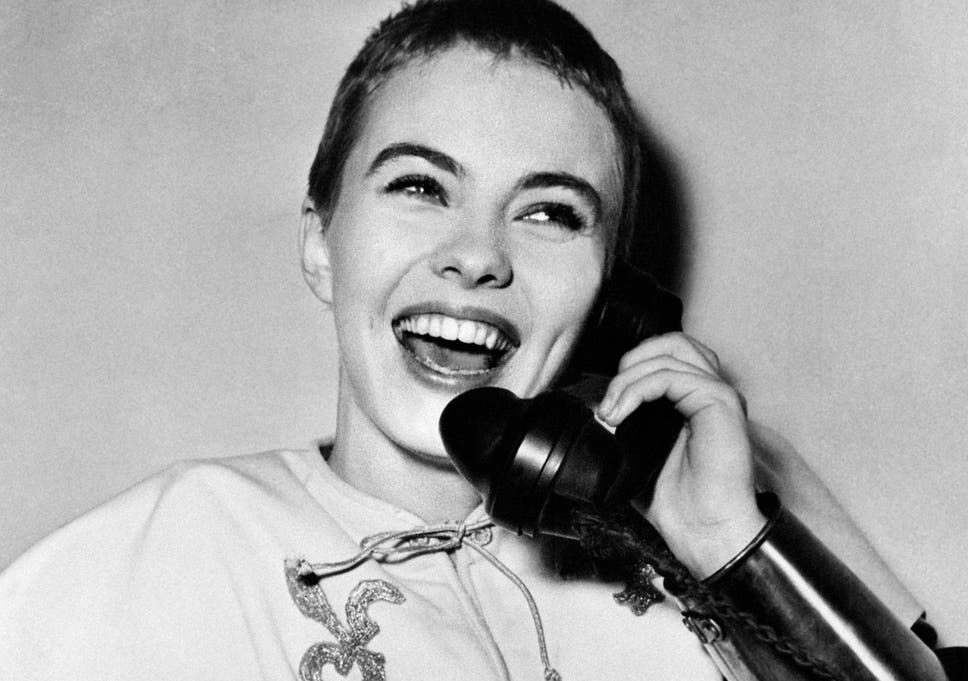

The woman Hoover set out to crush was the quintessential young American, “the golden sunflower girl” from the midwest, as she was characterised. A pharmacist’s daughter who had grown up in Marshalltown, Iowa, she had won Hollywood’s version of the Lottery by landing the lead role in Otto Preminger’s George Bernard Shaw adaptation, Saint Joan (1957). The autocratic Preminger had launched a nationwide talent hunt for a new Joan of Arc. A reported 18,000 girls had sent in pictures and resumes and 3,000 had been given personal auditions. Seberg got the part. She was the one, as TV show host Ed Sullivan put it, who had “caught lightning in a bottle”. It was the equivalent of Vivien Leigh being cast as Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind (1939).

Preminger was the perfect gentleman off-set but, when the cameras began to roll, he turned into a bad-tempered ogre. He used every ruse at his disposal to publicise the film and its new young star. It would have made the perfect story about overnight stardom if it hadn’t been for the fact that the film didn’t turn out very well. By her own admission, Seberg wasn’t obvious casting. She talked about being burnt at the stake twice, first in making the movie and then by the critics. Preminger cast her in a second film, Bonjour Tristesse (1958) but then discarded her. “He used me like a Kleenex and then threw me away”, is how she described her treatment at his hands.

The irony is that Preminger had been right all along. Seberg really was a special talent. She had a spontaneity, mischief and lambent grace on screen that immediately enraptured the young critics and would-be filmmakers from Cahiers du Cinéma in France. “When Jean Seberg is on the screen, which is all the time, you can’t look at anything else,” Francois Truffaut enthused about her performance in Bonjour Tristesse. Godard and Claude Chabrol were equally smitten with her.

In one of the more bizarre transformations in Hollywood history, the midwestern girl-next-door type became the sacred muse of the French Nouvelle Vague.

Seberg was wryly humorous about the effect she exercised on French male directors. “I was their new Jerry Lewis, I suppose,” she told journalist Rex Reed, comparing herself to the American comedian who made goofy films with Dean Martin and was treated with near contempt by American critics but revered as “Le Roi du Crazy” by their French counterparts. “Godard is like a Paul Klee painting, always hiding behind those funny dark glasses,” she suggested, going on to call the French auteurs who worshipped her “very strange little men”.

Thanks to Breathless, Seberg also became more highly valued back in Hollywood. Director Robert Rossen, who cast her in one of her greatest roles as the beautiful schizophrenic opposite Warren Beatty and Peter Fonda in Lillith (1964) spoke of her “flawed American girl quality, sort of like a cheerleader who’s cracked up”. She had prominent roles in all-star blockbusters like Airport (1970) and successfully held her own against such scene-stealers as Lee Marvin and Clint Eastwood in Paint Your Wagon (1969).

That, though, was the period before Hoover and the FBI set about destroying her just as surely as Otto Preminger had tried to create her as a star in the late Fifties in the first place.

Preminger and Hoover bookend her career. The media colluded with those two patriarchs, building her up and then knocking her down.

Elements of Seberg’s story are utterly heartbreaking. As Alistair Cooke told British listeners in one of his Letters from America broadcasts the week after her death, she took her prematurely born baby’s corpse back home to Iowa “in a glass coffin as a glaring proof that the baby was white – an excessive reaction perhaps but in 1970, she knew that the FBI could and did destroy hundreds of radicals and non radicals”.

On each anniversary of the baby’s death, her then-husband Romain Gary later revealed, she had attempted suicide.

Seberg continued to work throughout the 1970s, making an experimental film with Philippe Garrel and collaborating on projects with her third husband, Dennis Berry. She wrote to Ingmar Bergman, the great Swedish director, telling him that she looked a little like Bibi Andersson, who had starred in Bergman films from The Seventh Seal (1957) to Persona (1966), and expressing her fervent desire to work with him. The letter is kept in Bergman’s archives. He received it and read it – but didn’t deign to reply to it.

If Seberg was feeling marginalised and paranoid in her final years, you could hardly blame her given the FBI harassment, the upheaval in her private life and the alarming way her career had begun to creak. As her biographer David Richards notes, she was putting on weight, drinking too much and seemed to be in a state of permanent “psychological siege”. By the late 1970s, she was close to being forgotten. Her death, though, put her right back on the front pages. The public was reminded of just how abominably she had been treated both by Hollywood and by the FBI. There was a sense of frustration over talent that had never been properly fulfilled. Then again, as is pointed out in Mark Rappaport’s dramatised documentary, From The Journals of Jean Seberg (1995), most of her films may have been “mediocre”, but she made one or two “great ones” and that is more than in most careers. Now, with Stewart portraying her on screen (and already being talked up for awards), Seberg is likely to be rediscovered all over again

Seberg is released in UK cinemas on 10 January