In the middle of one late-August night in 1970, radicals bombed the Army Mathematics Research Center on the University of Wisconsin's Madison campus. The blast killed a scientist who was in his laboratory to catch up on work before a vacation.

In a letter published by the Milwaukee underground newspaper Kaleidoscope, a group calling itself the "New Year's Gang" took credit for the bombing and demanded the abolition of ROTC, as well as the release of three Vietnam veterans who'd bombed the power substation of a nearby army training base.

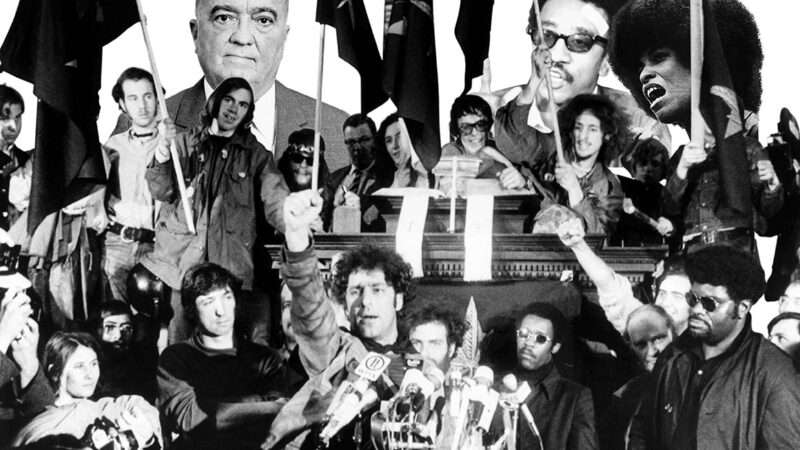

"If these demands are not met by October 30th," the letter read, "open warfare, kidnapping of important officials, and even assassination will not be ruled out." In an extraordinary action, a federal prosecutor jailed Kaleidoscope editor Mark Knops for six months for refusing to answer questions before a grand jury. Although the authorities thought they knew the identities of the four bombers within hours, they could not locate them; the suspects' names joined fellow radicals H. Rap Brown and Angela Davis on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. When Davis was captured, another militant, Bernardine Dohrn, moved onto the list within hours.

Bombs were exploding at least weekly in 1970—in Chicago, in Marin County, in Seattle, in Santa Barbara, in Long Island City, in Orlando. And American radicals were moving into other areas of adventurism. Members of Weatherman (a violent offshoot of Students for a Democratic Society) helped Timothy Leary escape from prison in San Luis Obispo in September. Two women who'd worked for the National Strike Information Center at Brandeis University—coordinating campus protests immediately following the May murder of four unarmed protestors by the National Guard at Kent State University—took part in a Boston bank robbery that left a police officer dead. They too went underground and joined the most wanted list.

The FBI stepped up its wiretapping and black-bag jobs in its dragnet for radicals. To get access to on-campus intelligence, the agency even lowered the minimum acceptable age for recruiting informants. But it was mostly coming up empty-handed.

"Face it," a Justice Department veteran told Newsweek, "we're in what amounts to a guerrilla war with the kids. And so far, the kids are winning."

Still, a 33-page FBI report shared information from a confidential source that the activities of the Yippies—a street-theater-oriented radical group of the wildest antiwar activists, which had been very active in 1968—were now "minimal" and that "the possibility exists that unless the non-leaders of the organization start planning activities, the organization will collapse." The Yippies had no formal membership and no bank account. In September, Abbie Hoffman, one of the most prominent Yippies and a member of the Chicago Seven, ducked out of a San Francisco fundraiser only minutes before he was scheduled to speak, leaving his attorney to pass along to the booing crowd Hoffman's complaint of "a lack of leadership in San Francisco for a revolutionary movement." An FBI source had an alternate explanation: Hoffman had been up on amphetamines for four days straight and "really freaked out."

The movement backlash against the Yippies, now perceived as ego-tripping celebrities, had begun. "It is tough being a leader when the movement has no leaders," chided one San Francisco underground paper. The FBI, naturally, was happy to help escalate any internecine conflicts. Soon afterward, a memo recommended that the agency's New York office anonymously mail a fake leaflet to "selected new left activists designed to broaden the gap between Abbott Howard Hoffman and Jerry Clyde Rubin, co-founders of the Youth International Party…to fragmentize the organization and hopefully lead to its complete disintegration."

The leaflet read:

ABBIE OINK HOFFMANWANTED

WANTED

FOR RIPPING OFF THE STREET PEOPLE,

PISSING ON THE REVOLUTION,

FOR FUCKING JERRY RUBIN AND YIP

The government struck a more sober tone when it warned that "several anarchistic groups" were planning to "blow up Federal Government operations and to kidnap government officials." In Michigan, a sergeant for the state police testified that the radical White Panther Party wanted to kidnap multiple congressmen to exchange for John Sinclair (a White Panther founder arrested on marijuana charges) and other prisoners. "Gerald Ford might be good for trading for Black Panther party leaders such as Huey Newton and Bobby Seale," the detective said, adding that Vice President Spiro Agnew was also considered a target.

Underground newspapers, once again, came under fire. In an October speech in Phoenix, Agnew castigated the Quicksilver Times by name and claimed that those who sold it "may be contributing to the maiming or death of other human beings." In New York, a man claiming to work for the government arrived at the offices of the Underground Press Syndicate, the national coordinating organization for the papers. He confided that the authorities "decided that the underground press was the main network causing all the trouble" and "had decided to wipe it out."

The FBI also visited the Philadelphia offices of Concert Hall, the agency that sold national advertisements for UPS papers. The Feds had previously come to Concert Hall looking for the White Panther fugitive Pun Plamondon, whom they claimed had received money from Concert Hall, and they visited again after Concert Hall printed Abbie Hoffman's book Woodstock Nation. Now, they said, they had information that Bernardine Dohrn had been involved with a festival that Concert Hall had helped put on.

The actual existence of such leads is, in retrospect, debatable. More likely, they were just a pretense for harassment. A memo from the Philadelphia FBI office at the time indicated a consensus that "more interviews with those subjects and hangers-on are in order for plenty of reasons, chief of which are it will enhance the paranoia endemic in these circles."

Turning the Grand Jury Process Upside Down

The Arizona conservative Barry Goldwater had popularized the slogan "law and order" in his 1964 presidential campaign. The Phoenix lawyer who suggested the strategy to Goldwater, Richard Kleindienst, had gone on to work for Richard Nixon's 1968 campaign, and after Nixon won the presidency, Kleindienst was rewarded with the position of deputy attorney general.

Kleindienst quickly earned the nickname "Mr. Tough" and a reputation as something of a hatchet man. One nationally syndicated column described him as "boisterous," a "Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard" who "often hides a brilliant mind with discourtesy bordering on crudeness." In the early months of the administration, Kleindienst caused a stir when an interviewer quoted him as saying "people who demonstrate in a manner to interfere with others should be rounded up and put in a detention camp."

With the ear of his boss, Attorney General John Mitchell, Kleindienst immediately recommended hiring William Rehnquist, a Phoenix lawyer whose long sideburns, pink shirts, and loud ties belied his right-wing ideology. Rehnquist was put in charge of the Office of Legal Counsel, and within months he made headlines for a speech warning that the "barbarians of the New Left" posed "a threat to the notion of a government of law which is every bit as serious as the 'crime wave' in our cities."

If force was required to extinguish that threat, Rehnquist said, so be it. "Disobedience cannot be tolerated, whether it be violent or nonviolent disobedience."

In the fall of 1970, the Nixon administration made a series of moves designed to vanquish dissent. First, Mitchell and Kleindienst prepared to revive the nearly dormant Internal Security Division (ISD) of the Justice Department. Kleindienst's best pal from Arizona, Robert Mardian, stepped into the role as assistant attorney general in charge of the division.

In mid-October, Nixon signed the 1970 Organized Crime Control Act, which, among other measures, allowed the government to invert the grand jury system. Grand juries, originally designed as a check on overzealous prosecutions, were held in secret to protect identities of both witnesses and falsely accused individuals. Questioning was done without lawyers present because witness immunity was guaranteed. But the Organized Crime Control Act authorized the misleadingly named "use immunity."

Held as unconstitutional since the 19th century, use immunity meant that witnesses could still be indicted for crimes investigated by the grand jury, provided that the crimes could be "independently" corroborated—but because of that pretense of "immunity," the witnesses were not allowed to exercise the Fifth Amendment. They could be jailed for contempt at the first moment they refused to answer a question.

The government could commence grand juries anywhere in the country, at any time, for up to 18 months, and renewable after that. A witness who refused to testify could be jailed for those same 18-month terms. Even if a grand jury didn't prove a crime, it could tie up both the movement leaders and the lawyers who defended them.

By November, young left-wing radicals accounted for the bulk of the FBI's list of most wanted fugitives. The ISD's staff of lawyers, which had withered from 96 to 42, built back up, and suddenly Mardian found himself the third-most-powerful man in the Department of Justice.

Mitchell then seized on the White Panther Party to get a judicial imprimatur for the crusade against the radical Left. He filed an affidavit in United States v. Sinclair—a case charging White Panthers John Sinclair, Pun Plamondon, and Jack Forrest with conspiring to bomb a CIA building in September 1968—that admitted the government had picked up Plamondon's conversations when it was conducting warrantless wiretaps. Then, reviving an argument that he'd made during the Chicago Seven case, Mitchell claimed that the president of the United States had inherent constitutional power to authorize such surveillance in the name of national security.

'There Is an FBI Agent Behind Every Mailbox'

At the end of 1970, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover appeared before a Senate appropriations subcommittee to ask for $14 million for a thousand new field agents. Then, despite advice from the ISD (and others) that there was insufficient evidence, Hoover announced that he had information about a threat from a group made up of priests, nuns, students, and teachers. He claimed the group was planning to explode electrical conduits and steam pipes in D.C. and to kidnap a White House official as ransom for the end of bombing in Asia and the release of political prisoners.

Hoover's bombastic speech ensured that the ISD had no choice but to indict the group, soon to be known as the Harrisburg Seven, in 1971. The ISD's first major case would be a weak one. "There's goddamn no telling what we would have if Hoover hadn't talked," Mardian said later, as reported in the 1972 book The FBI and the Berrigans by Jack Nelson and Ronald J. Ostrow. "We depended on informants, and they shut up after he testified." One of the witnesses called, a 52-year-old nun, refused to appear. "The evidence on the basis of which I have been named as an unindicted co-conspirator, subpoenaed to testify and asked questions, was secured by illegal wiretaps," she said. She was jailed.

That same day in Detroit, the district court hearing United States v. Sinclair rejected the reasoning behind Mitchell's affidavit claiming a constitutional power for warrantless wiretapping. "An idea which seems to permeate much of the government's argument is that a dissident domestic organization is akin to an unfriendly foreign power and must be dealt with in the same fashion," Judge Damon Keith wrote in his ruling. "In our democracy all men are to receive equal justice regardless of their political beliefs or persuasions."

After extensive meetings between Mitchell and Mardian, the Justice Department decided to file a mandamus appeal, bringing Keith's ruling on the wiretap issue before the Sixth Circuit.

Meanwhile, more information about the surveillance of American citizens came to light when a group of former army intelligence agents testified before a Senate subcommittee. For the past few years, the U.S. Army's Counterintelligence Analysis Branch (CIAB) had received information "from approximately fifty agencies within the U.S. intelligence community," cross-referenced files, and sometimes passed information on to other agencies.

One of these CIAB agents, Ralph Stein, was nicknamed "Mr. Radical" and had specialized in the New Left and the underground press. He testified that he'd also been ordered to share his findings with men from the CIA, who, he later told The New York Times, were especially interested in learning more about radical editors and writers, asking "a lot of questions that indicated that they had already examined some of the underground publications in question" and seeming to have already "investigated the personalities."

Of the names in the Army's files, Stein testified, "the overwhelming percentage are of people who did nothing more than exercise basic constitutional rights and civil liberties, and who are anonymous Americans." And a former army captain revealed that an Interdivisional Intelligence Unit in the Justice Department had since supplanted the Army's counterintelligence branch, maintaining a "political computer" that "can produce a rundown on almost any past or coming demonstration of size, which will include all stored information on the membership, ideology, and plans of the sponsors."

Shortly after Stein's testimony, The Washington Post reported that an anonymous group calling itself the Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI had responded to the Harrisburg Seven indictments by burglarizing files from the bureau's offices in Media, Pennsylvania. Among the sensational contents of these files were descriptions of FBI policy on hiring student informers, a memo in which Hoover ordered surveillance on student groups that "organized to project the demands of black students," plans to develop informant networks in "ghetto areas," and stern reminders to informants that they weren't supposed to assault policemen.

The stolen documents also revealed that the aims of the bureau went beyond law enforcement and into the realm of psychology. The agency was determined, as one memo put it, "to get the point across there is an FBI agent behind every mailbox." Eventually, the files were determined to be part of a widespread counterintelligence program called COINTELPRO. Its mission was not only to thwart black and leftist activities but also to sow suspicion among dissenters.

As 200,000 demonstrators prepared for a May Day antiwar protest at the Capitol, Mitchell gave a speech to rally support for the warrantless wiretapping policy. "We need intelligence on the movements of suspected conspirators, not formal evidence on which to convict them," he said, touting the value of the hundreds of wiretaps he'd authorized. "In order for a national security wiretap to do any good, it should come near the beginning of the investigation."

"This is not a police state," Nixon insisted at a press conference, but on the very same day Richard Kleindienst cooked up a plan for the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs to monitor and record drug use among May Day activists as a pretense for canceling park protests. "Their plan is now to bust the demonstrators Sunday morning, and probably move in with narcotics agents to arrest as many as they can," wrote White House chief of staff H.R. Haldeman in his diary that day. "Thus they think we'll bust up their plans and make it hard for them to do their traffic-stopping exercise on Monday."

The May Day demonstrations in D.C. resulted in the largest mass arrests in U.S. history, with more than 12,000 people detained. When local precincts were stretched to capacity, thousands were crowded into a Washington Redskins practice field surrounded by cyclone fencing or into the exercise yard of a jail and then bused into the Washington Coliseum. A quarter of those were swept up during a protest outside the Justice Department; Kleindienst and Mardian joined Mitchell on his office balcony to gaze down at the roundup. While Mitchell puffed on his pipe, Mardian snapped photos of the masses below.

Grand Juries as Information-Laundering Operations

The FBI had arrested an activist named Leslie Bacon in connection with a March 1 bomb explosion in a Capitol building bathroom. She became an overnight celebrity within the movement, and her treatment was symptomatic of out-of-control federal policy toward the antiwar radical movement in the early 1970s.

The ISD's chief litigator, Guy Goodwin, employed lines of questioning that went something like this: Tell the grand jury, please, where you were employed during the year 1970, by whom you are employed during the year 1970, how long you have been so employed, and what the amount of remuneration for your employment has been during the year 1970. I want you to describe for the grand jury every occasion during the year 1970, when you have been in contact with, attended meetings which were conducted by, or attended by, or been any place when any individual spoke whom you knew to be associated with or affiliated with Students for a Democratic Society, the Weathermen, the Communist Party, or any other organization advocating revolutionary overthrow of the United States, describing for the grand jury when these incidents occurred, where they occurred, who was present and what was said by all persons there and what you did at the time that you were in these meetings, groups, associations or conversations.

"Goodwin just has totally evil vibes," Bacon told the Liberation News Service of the slick, impeccably coiffed witchfinder. In the next few years, the ISD would conduct more than 100 grand juries in 80 cities. It would subpoena thousands of witnesses, in some cases forcing them to travel from one part of the country to another without lawyers. The grand juries would be used not only to gather new information but also, by steering scared witnesses to confirm what had previously been learned illegally by FBI surveillance or black-bag jobs, to launder information for prosecutions. Goodwin often offered immunity and then threatened contempt sentences if witnesses didn't testify against associates.

Investigations of radicals that had previously been conducted independently by the FBI, the Secret Service, and the Treasury were now coordinated under the aegis of the ISD, which used the Interdivisional Information Unit's computer system to consolidate thousands of dossiers. Goodwin crossed the country, connecting the cases together like they were one grand conspiracy, muddying distinctions between political activism and violent crime.

The Fateful Wiretap Case

While the desperate federal law enforcement war on the antiwar movement continued through the early 1970s, the Justice Department was fighting to win the ruling on the warrantless wiretapping so central to that war.

In late February 1972, United States v. United States District Court went to the Supreme Court. Because it would test the government's right to wiretap without warrant, it would have a major impact on other radical trials. Arthur Kinoy, a former law partner of prominent radical attorney William Kunstler, was to argue for the defense. Observing from chairs in the back of the chamber were John and Leni Sinclair in their purple White Panther Party T-shirts.

To their surprise, the head of the ISD appeared in the courtroom. Mardian himself would argue for the prosecution. Mardian's argument was nothing less than a power grab for unchecked presidential power. The privacy of the American citizen, Mardian said, was better protected if the president had the unchecked authority to wiretap. "This Court must, as a coordinate branch of government, rely almost entirely on the integrity of the Executive Branch," he insisted.

Kinoy would call this "one of the most dangerous moments in the long history of the Supreme Court" in his memoirs. "It was one of those rare moments when for an instant the outer wrappings of rationalization are peeled off and, like a flash, the truth is revealed. Without hesitation or apology, Mardian demanded from the Court judicial approval for a course of conduct that would place in the President, in Nixon, the unreviewable and absolute power to suspend the provisions of the written Constitution, the fundamental law of the land."

Only weeks earlier, White House aide H.R. Haldeman had accused opponents of Nixon's Vietnam policy of "aiding and abetting the enemy." Would these critics, Kinoy asked, be included in the scope of domestic intelligence? Now the matter would await the decision of the court.

Kleindienst wrote in his memoir that, in regard to wiretapping, the issue of national security "had been handled as a hot potato by each succeeding attorney general. Sooner or later the potato had to be tossed into the hands of the Supreme Court." Kleindienst then chose curious language to describe the Keith case: "A black federal district judge in Michigan, in dealing with the situation of another black [sic] by the name of Plamondon, made the critical toss."

On Monday, June 19, 1972, by a unanimous 8–0 decision, the Supreme Court upheld Keith's ruling on wiretaps, effectively outlawing most of the "national security" wiretaps on "domestic subversives." (It was 8–0 because one newly appointed Supreme Court justice—Mardian's old crony Rehnquist—had recused himself. As the head of the Office of Legal Counsel, Rehnquist had authored the administration's position on wiretapping.)

The close proximity in time between this June 19 ruling and another momentous incident, two nights earlier, is intriguing. Attorneys for the defense later theorized that there was an advance leak from somewhere in the court that the government was going to lose the case that Monday, and that was why five men had broken into the offices of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate Hotel on Saturday, June 17. They were sent in, the theory goes, to remove previous taps.

"If the case had been won" by the government, wrote Arthur Kinoy, "and the Watergate wiretapping was later accidentally exposed, the Attorney General, acting for the President, could openly acknowledge his authorization, and the entire affair would be covered with the mantle of legality. But if the case had been lost, and the wiretapping was subsequently exposed or discovered, there would be no explanation at all available to the administration."

L. Patrick Gray, acting director of the FBI, moved quickly to have other devices removed. "I knew from my earlier domestic intelligence briefing with [FBI agents] Ed Miller and Mark [Felt] that we had several such warrantless domestic taps and microphones in place, so I told Mark to meet with Dick Kleindienst and then to get written instructions on which ones to cancel," Gray wrote in his 2008 memoir, In Nixon's Web: A Year in the Crosshairs of Watergate. "I also told Mark to brief Dick on the status of the Watergate investigation.…At his meeting with Mark that afternoon in Washington, Dick ordered that four telephone taps and two hidden microphones be removed from the Black Panther and Weather Underground targets but to leave in place the one directed at the Communist Party, USA."

"You could probably count them on the fingers of both hands," Kleindienst, just confirmed as attorney general, told Time the day after the ruling. "We only used them where we thought there was a threat of violence. I had just authorized a couple more last week, but I'm not going to talk about any individual taps. If I say anything, they [defendants and suspects] will come in and ask for transcripts of everything we took."

Wouldn't it be proper, Time's reporter asked Kleindienst, for the Justice Department to notify anyone who had been illegally overheard?

"Hell, no," Kleindienst replied. "Our duty is to prosecute persons who commit crimes. We don't have to confess our sins anywhere, like some bleeding heart. We were acting in good faith."

The fallout from the Keith decision was enormous. With much of the government's evidence now firmly ruled illegal, it would sink longstanding conspiracy cases involving the Weather Underground, the Black Panthers, and the Pentagon Papers. The government's war on radicalism had ironically engendered a big part of its own defeat.

This article is adapted from Agents of Chaos: Thomas King Forçade, High Times, and the Paranoid End of the 1970s by permission of Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group.

The post How Hippies Saved the Fourth Amendment appeared first on Reason.com.