One bullet after another zips toward the target, the discharged shell casings bouncing off the firing table, the ground and his neighbor’s shoulder.

Melissa Lulik doesn’t seem to mind or even notice the bits of brass hitting her cardigan. She’s too busy peering through the scope of her own AR-15 rifle, a weapon she’s nicknamed “Margo.”

The smell of gunpowder hangs in the air as Lulik takes aim at a target 25 yards away and starts firing.

Later, Lulik, 40, a hair stylist from DuPage County, reflects on why she’s drawn to powerful firearms and ammunition and why she first came to this outdoor range in Waterman.

“I wanted good habits,” Lulik says. “And I met these awesome ladies.”

She raises a hand in the direction of three friends, all middle-aged women: an insurance underwriter, an architect and a mortgage loan originator.

Not long ago, the big guns and high-capacity magazines Lulik and her friends use at ranges and in competitions weren’t so common among civilians.

Now, you can easily buy them online or in stores. You don’t need a license or a background check to buy one. Extended-capacity magazines — which hold 10 or more bullets and can be used with handguns as well as rifles — have become commonplace even as they’ve been banned in some places.

The privately owned companies that are the big players in the industry don’t report sales figures or how many of the magazines they produce. One indication of how ubiquitous they are comes from the National Shooting Sports Foundation, an industry group. In 2018, the latest data it has on them, the foundation estimated that 304 million detachable magazines were in circulation nationwide — including 80 million able to hold 30 or more rounds.

The magazines have become must-haves for many law-abiding gun owners, who often pair them with AR-15-style semi-automatic rifles. They also have become standard fare for criminals.

Large-capacity magazines are illegal to sell or possess in Chicago, which bans magazines that hold more than 15 rounds, and suburban Cook County, where the county’s ban starts after 10 rounds.

But they’re still easy to obtain. All it takes is driving to a store in a neighboring county that sells them.

A Chicago Sun-Times reporter was able to buy a 32-round magazine — for $37.99, plus tax — by going just outside the city to Hammond, Indiana. Seeing a Chicago address on an ID didn’t keep the store from selling the magazine or questioning whether it would be taken back to the city. Nor is a seller required to ask.

Police and federal authorities say criminals in Chicago increasingly have been using extended magazines with handguns to which an illegal device, known on the streets as a “switch,” has been attached. That gives them a now-fully automatic firearm — a weapon that’s illegal in the United States under a federal ban on machine guns.

The growing popularity of that illicit pairing has fueled renewed calls around the country for restrictions on the magazines.

“It’s obviously putting the capacity to fire a lot more rounds a lot more quickly into the hands of consumers,” says Adam Skaggs, chief counsel and policy director for Giffords Law Center, an advocacy group that lobbies for stricter gun laws, including limits on magazines. “In the vast majority of the country, these are legal to possess, these are legal to sell, and there’s no background check.”

For some law-abiding gun owners, the concern that criminals have high-capacity magazines in their armory reinforces a message the firearms industry has been happy to spread: To stay safe, people need powerful weapons and lots of ammo in case the bad guys attack.

Melissa Lulik says she was “anti-gun” for years. But, when “things got really kind of crazy” in 2020, with the start of the coronavirus outbreak and the violence that followed the police killing in Minneapolis of George Floyd, she began feeling she wasn’t safe.

“You start imagining that everything is out of your control,” Lulik says.

She decided to take a shooting lesson. She eventually bought three handguns and the AR-15, which holds 30 rounds, concerned that someone might break in to her home.

“The larger capacity is just for ease,” Lulik says. “To know that you don’t have to stumble around in the middle of the night, if there’s an intruder, looking for your magazines.”

Marketing to the masses

In 1994, Congress enacted a national ban on so-called assault weapons. It remained the law of the land until September 2004. During the ban, the production of new magazines that could hold dozens of rounds was outlawed, though the sale of existing magazines was not.

With the end of the ban, gun makers began producing and selling “black rifles” that could be accessorized in a similar fashion to those that soldiers fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan were using. That included large-capacity magazines.

Ryan Busse, a former gun company executive with Kimber Manufacturing who left the industry in 2020, says he saw a shift in marketing tactics after the federal assault weapons ban expired that began with gun industry upstarts but came to also include stalwarts like Smith & Wesson.

Typifying that, according to Busse, was the tagline that Daniel Defense, a Georgia rifle maker, used in ads. “USE WHAT THEY USE,” it encouraged consumers, with images of soldiers in combat.

The message, according to Busse, who wrote the book “Gunfight: My Battle Against the Industry that Radicalized America,” was this: “You get to become a special forces badass without any of the training they do.”

“It’s really highly ingrained,” Busse says of marketing that pairs notions of “good guys with guns” with worries about government tyranny. “It’s almost telling them that, if they’re going to be good, patriotic citizens, they must have these guns.”

For some, an aid to target practice

Though Chicago and Cook County ban extended-capacity magazines, farther from the city it’s common to see them being used with AR-15s and similar semi-automatic rifles for target shooting.

Like at a shooting event at the gun range in Waterman in DeKalb County, where, after driving past fields of corn and small towns where American flags flutter along historic Lincoln Highway, you could see men and women of all ages firing at targets using handguns and semi-automatic rifles.

The “AR” in AR-15 rifles originally was for the brand ArmaLite. The National Rifle Association has recast “AR” as “America’s Rifle.” The black rifles, first made by Colt, are now produced by about 500 manufacturers.

A selling point is that these rifles are easy to use and to customize. It’s easy to pop in a big-capacity magazine or even a drum filled with 60 or 100 rounds and then, when you’re done shooting, to pop it back out.

Julie Puls, a firearms instructor who heads the Naperville chapter of a women’s shooting group called A Girl & A Gun, says the magazines have become a necessary part of her gun kit. Why? “Because the criminals have high-capacity magazines,” Puls says.

Magpul Industries is one of the leading manufacturers of high-capacity magazines. It specializes in lightweight polymer magazines for pistols and rifles.

The privately owned Austin, Texas, company doesn’t disclose profits or other financial details. But The Trace, a news website focused on gun violence, reported that Magpul got $14.8 million in financing in 2011 from Triangle Capital, a private equity firm that also has backed companies including Tommy Bahama and Liz Lange Maternity, as well as money from another private equity firm known for restaurant investments.

Last year, in a newspaper opinion piece, Duane Liptak, a Magpul executive vice president, wrote that the company moved its headquarters to Texas in 2013 after its previous home state of Colorado banned high-capacity magazines. According to Liptak, Colorado “lost $85 million in annual taxes and hundreds of local employees.”

‘A better chance of survival’

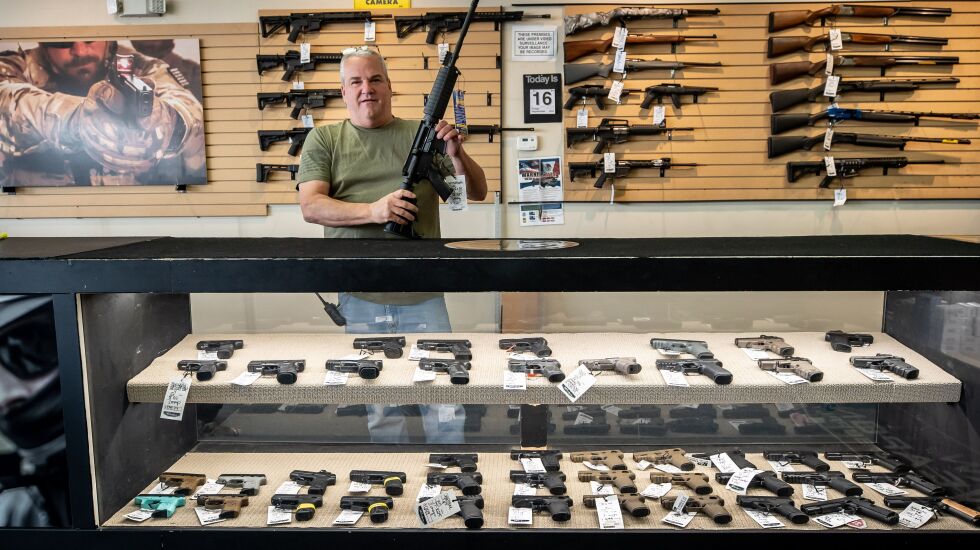

Robert Bevis, who owns Law Weapons & Supply in Naperville, says many of his customers say they want large-capacity magazines for protection. Having immediate access to those extra rounds could be the deciding factor if someone faced more than one assailant, according to Bevis, who is fighting Naperville in federal court over an ordinance it passed this summer that bans certain types of semi-automatic weapons.

Bevis doesn’t buy the argument made by the Giffords Law Center and others who oppose the manufacture and sale of extended-capacity magazines and say getting rid of them might result in innocent people potentially being able to disarm a mass shooter who has stopped to reload.

If 10-round magazines were the maximum allowed, Bevis says, a shooter “could do 10 and 10 more and 10 more and 10 more,” taking maybe two seconds each time to reload. Compared to having a larger-capacity magazine, he says, “It doesn’t make a big difference.”

He says that even if high-capacity magazines were totally banned, criminals could make their own with a 3D printer or by fashioning them out of metal.

“When nobody can help you, you can defend yourself,” Bevis says of keeping the magazines legal. “Don’t you at least want to have a chance? Having more rounds gives you a better chance of survival. It helps to level the playing field, I’d say.”

Large-capacity magazines are legal in most of Illinois. Besides Chicago and Cook County, places with local bans include Oak Park, Aurora and Highland Park — the scene of the July 4 massacre in which a gunman used multiple large magazines.

States that have restrictions on magazines include New York, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Connecticut, Maryland, Delaware, Washington, California, Colorado and Hawaii. Washington, D.C., also restricts them. Many of these laws are facing court challenges over whether they amount to unconstitutional violations of the Second Amendment.

Driving around local bans

As the Highland Park parade massacre showed, a ban doesn’t mean someone can’t get around it by buying magazines elsewhere.

It took less than an hour for a Sun-Times reporter to drive from the North Side of Chicago to the sprawling Cabela’s sporting-goods store in Hammond, just over the Cook County border. Dozens of high-capacity magazines were displayed on racks.

The cashier, required to verify that buyers are of legal age, asked for identification before ringing up the purchase of a Pro Mag 32-round magazine that’s compatible with a Glock 9mm handgun for $37.99, plus tax, paid in cash, but didn’t raise any objection to the reporter’s Illinois driver’s license showing an address in Chicago, where it’s illegal to possess such a magazine. The Sun-Times reporter returned the 32-round magazine to Cabela’s for a refund before driving back across the state line into the city.

Cabela’s, which didn’t respond to a request for comment, isn’t required to limit sales of the magazines only to people who live in places where there’s no ban.

Nor is there any law that would prevent a Chicagoan from leaving Cook County and loading up on as many magazines as the buyer might want.

“That’s the problem with sort of the patchwork of laws,” says Skaggs of the Giffords Law Center. “It’s troubling that cities like Chicago that are trying to pass laws to protect the public — it just shows how impossible a task that is.”

There also are numerous online sellers. All that an online buyer needs is a mailing address in a location that doesn’t ban large-capacity magazines.

Steve Lindley, a program manager for the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence who formerly headed the California Department of Justice’s firearms bureau, is among those calling for a national limit on the size of magazines.

“We need a national fix,” he says.

If Congress put a limit on how big a magazine could legally be, Lindley says, “You won’t stop all mass shootings. But, when you have less bullets in the gun, you have less victims.”

Of gun enthusiasts who say they need high-capacity magazines, he says: “How many bullets do you really need? If you need that many bullets, you’re probably a very bad shot.”