Cheers and singing explode from the plaza outside Hong Kong Space Museum as hundreds of lasers converge like fireflies upon the building’s domed exterior.

After weeks of tear gas and heartache, protesters are gathered to mock the police’s designation of laser pointers as “offensive weapons” by holding a laser party. Instead of the sombre hymns heard echoing around the streets after months of civil disobedience, this near-rave is soundtracked by In the Lasers, a thumping disco hit released in 1983 by Roman Tam.

Tam was known as the “Godfather of Canto-pop”, a genre synonymous with Hong Kong and renowned for its heavy drama, emotion and ostentation. Although he died 17 years ago today, aged 57, he is still held dear by Hongkongers, who draw upon hits from his 56 albums to soundtrack the highs and lows of life in an ever-changing city.

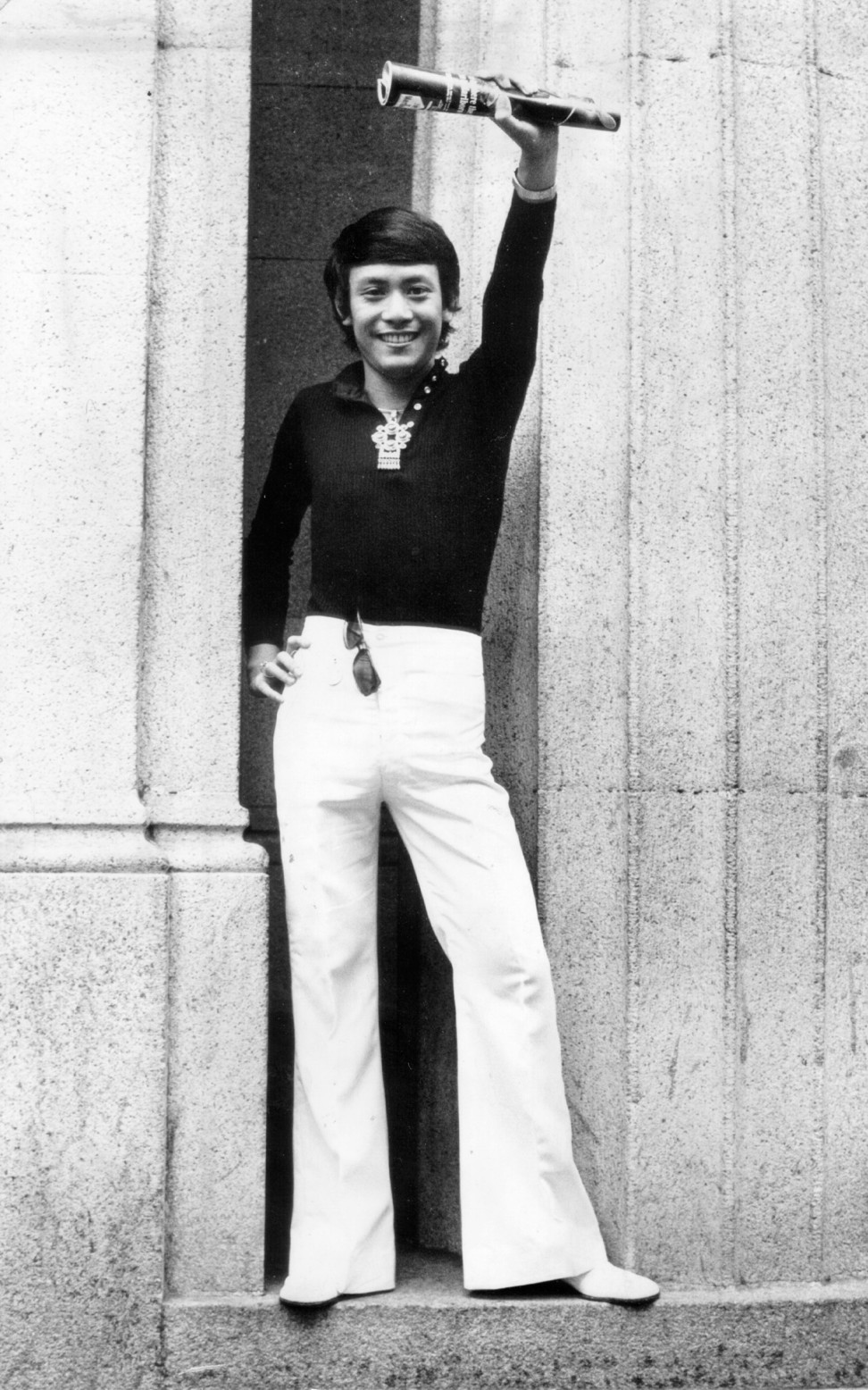

Tam’s success was not confined solely to Hong Kong or Asia: this year also marks the 40th anniversary of his landmark concerts at the Royal Albert Hall in London and New York’s Carnegie Hall. In his heyday in the late ’70s through to the mid-’80s, his influence was ubiquitous throughout Hong Kong entertainment and culture, from film and television to fashion and theatre.

It was his television work that propelled him into the homes of Hongkongers, who would crowd around screens in the evenings to watch the RTHK kitchen sink drama Below the Lion Rock, for which Tam sang the eponymous opening theme.

During this summer’s protest movement against a now-withdrawn extradition bill, the song, with its themes of unity through struggle, became a common refrain, unifying black-clad marchers.

“In life, there is joy, but inevitably there is also sorrow/We met underneath the Lion Rock,” go the lyrics to the song, often described as Hong Kong’s unofficial anthem. Tam’s precise diction and recognisable sonorous warbling singled him out among the era’s performers.

Canto-pop’s roots date back to the 1920s, when Western-influenced music arrived in China and musicians began infusing Mandarin vocals with genres like jazz, according to James Wong Jum-sum, perhaps Hong Kong’s most decorated songwriter, who wrote a thesis on Canto-pop in 2003.

When it came to power in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party denounced the genre as “decadent” and its locus moved to Hong Kong and the current genre began taking shape – with Cantonese lyrics.

If Sam Hui Koon-kit – “the God of song” – is credited with popularising a more rock ‘n’ roll-sounding Canto-pop in the ’60s, it was Tam who amplified it with extravagant stage shows, costumes and dancing from the late ’70s onwards – and made it unabashedly Hong Kong.

“Roman blended modern and traditional influences: he brought elements of Chinese opera with pop influence from Japan,” says Yuen Chi-chung, a prominent music critic and DJ. “He had that ‘bling-bling’ style and was always changing his look and sound. If you were a fan of him, you weren’t just into one kind of music. There’s no one like him now; he was very unique.”

Roman Tam Pak-sin was born in mountainous western China and loved music from an early age. His mother and three sisters were fans of Cantonese opera, exposing a young Tam to a style of performance that would play out across his future career.

After both of his parents died before he turned 13, he moved to Hong Kong to live with relatives and worked at a tailors, an amusement park, a bank and theatre, and eventually began performing in bars as a singer.

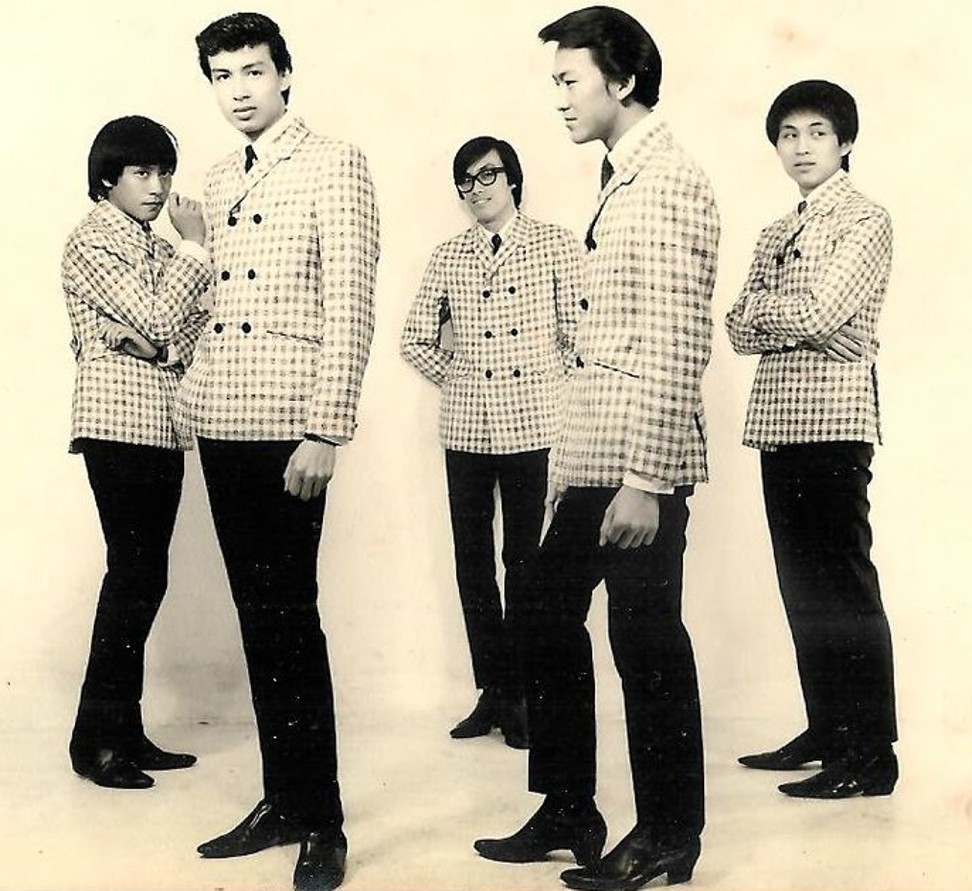

In the late ’60s, he fronted the cover band Roman and the Four Steps, who channelled The Beatles with their side-swept haircuts and slim suits.

After the group disbanded in 1971, Tam tried out a short-lived comedy act before finding himself in Japan, where he acquired a recording manager and won a televised talent contest, having learned to sing in Japanese.

This industry experience would fortify his growing stardom on his return to Hong Kong, where, in 1978, he lent his vocals to the theme tune of TVB series A House is Not a Home.

From there, he applied a relentless work ethic to recording and performing, singing the themes to other dramas, including Flying Daggers and The Legend of the Condor Heroes – the latter, duetted with Jenny Tseng, would become a favourite in his repertoire. He performed across Asia, the US and Britain, entertaining the large populations of Chinese fans who had settled abroad.

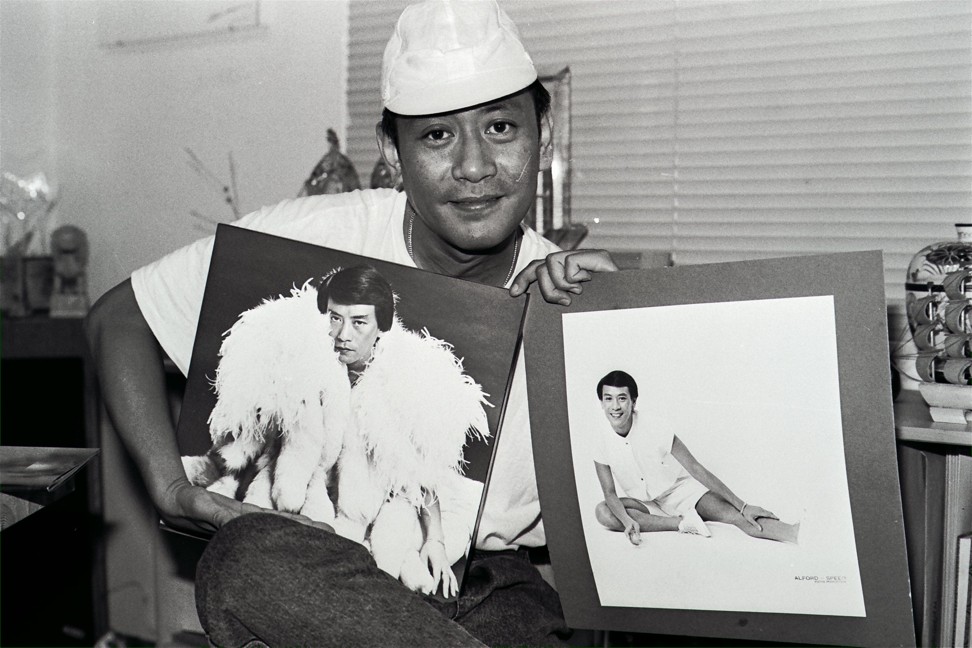

“I would like to use my showmanship and talent to cross cultural barriers all around the world, not just in Hong Kong,” he told the Post at the height of his fame in 1983.

He particularly excelled in delivering rousing tracks about togetherness and triumph over adversity, which appealed at a time of economic expansion as the city transformed from a haven for mainland refugees after World War II into a manufacturing powerhouse.

Record collector Fion Cheng drops the needle down on Tam’s seminal 1986 album, Toiling Life in Wind and Rain – her favourite record – on the turntable in her shop, Lamma Vinyl. As crackling gives way to an evocative flute intro, she rubs her arms to dispel the goosebumps that have risen, then laughs.

“Maybe I’m sensitive but I love his words. They represent Hong Kong people: no matter what problems they’re struggling with, whether they’re rich or poor, they can carry on even in very difficult times, like now.”

Like many Hongkongers, Cheng grew up listening to Tam’s music. Her family was lucky enough to own a television set, and from the age of six she would watch action- and romance-packed series such as The Legend of the Flying Condors. Living in a neighbourhood directly beneath Lion Rock, which looms over Hong Kong’s Kowloon district, Cheng felt particularly moved by Tam’s dramatic balladry.

“These songs represented Hong Kong at that time,” she says, flicking through the record’s booklet. “He writes about sticking together even when you can’t see what the future holds. So why did his songs make such an impression on me when I was a child? Because the lyrics and the melodies were so good. They told a story.”

When he walked onto the stage, everybody went crazy. You couldn’t take your eyes off him – Willy Han, bass player in Roman and the Four Steps, on Tam performing

As Cheng reloads the album for another play, a young customer browsing music with his girlfriend looks up, smiling widely at the opening bars.

“I grew up listening to this music,” says 30-year-old Simon Chung Chi-hung. “These songs are much older than me, but my family would listen to these kinds of songs every day when I was growing up.”

Chung had watched videos of protesters younger than himself singing Tam’s song at the laser dance party and felt inspired by their optimism.

“After all the stress and tension, that night was like an oasis. When I saw these people singing and dancing happily, it made me think how much they deserve a bright future.”

Brian Leung Siu-fai, 55, was there on that laser-lit August night at the Space Museum.

“That rally was different,” says the long-standing RTHK Radio 2 DJ. “People had gathered to shine lasers, then someone started playing In the Lasers and everybody started singing along. I was surprised that these kids knew this ’80s song.

“It was like comic relief. After the last few months, we desperately needed that particular night, so thanks to Roman for that.”

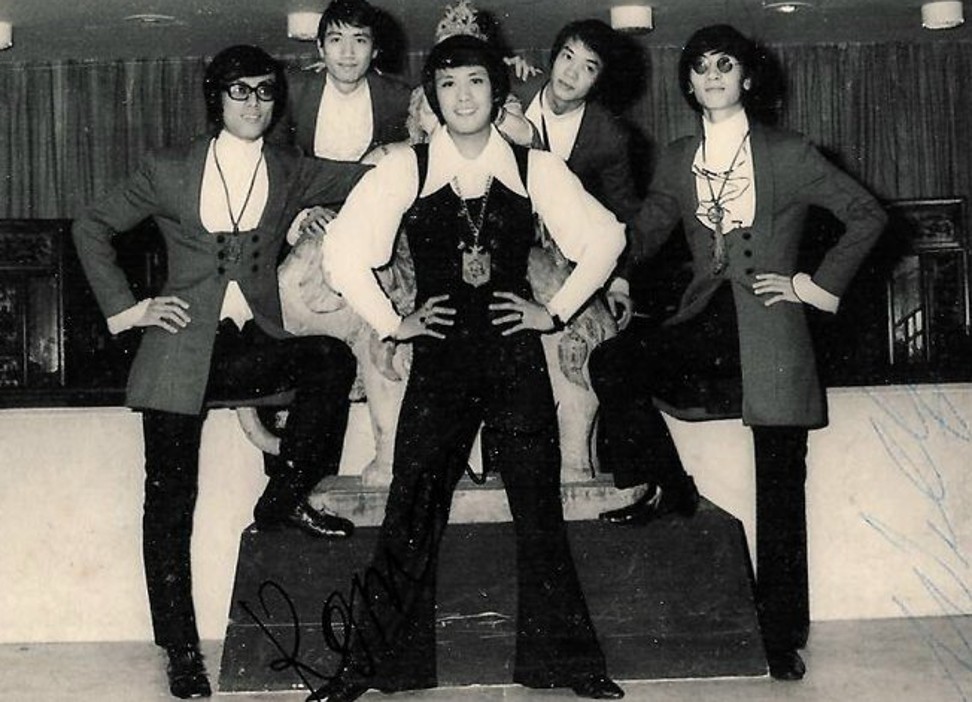

During his time in the public eye, Tam’s chameleonic sound and image – one minute a soulful, suave crooner, the next a dancing diva-esque acrobat – played with notions of gender and masculinity.

But for all his onstage exuberance, Tam was a very private star, and little is known about his personal life: he died having never married.

In the ’70s and ’80s, when discussions around sexuality were kept firmly out of public discourse (homosexuality was not legalised in Hong Kong until 1991), his camp and androgynous performance style was groundbreaking for young Hongkongers, like Leung, who were coming to terms with their sexuality in a highly conservative society.

“Tam transcended being straight or gay, male or female,” Leung says. “When I saw him perform onstage, he was like an alien. He could be everything for everyone.”

Leung is also chief operating officer of BigLove Alliance, an LGBT rights group co-founded in 2013 by a number of people including musicians Anthony Wong Yiu-ming and Denise Ho Wan-sze, who both came out as gay in 2012.

“Roman taught me you can be anything,” Leung says. “As a gay kid myself, he helped me to redefine what masculinity was about because he had such a powerful and masculine voice when he sang martial arts drama themes. But, at the same time, on stage he was so flamboyant; he was like Hong Kong’s Liberace.

“We’ve only just started talking about toxic masculinity in recent years. In the ’70s, Tam was already saying, ‘F**k toxic masculinity; just listen to my voice’ … He was masculine and unapologetically feminine at the same time. It didn’t matter because he was so good.”

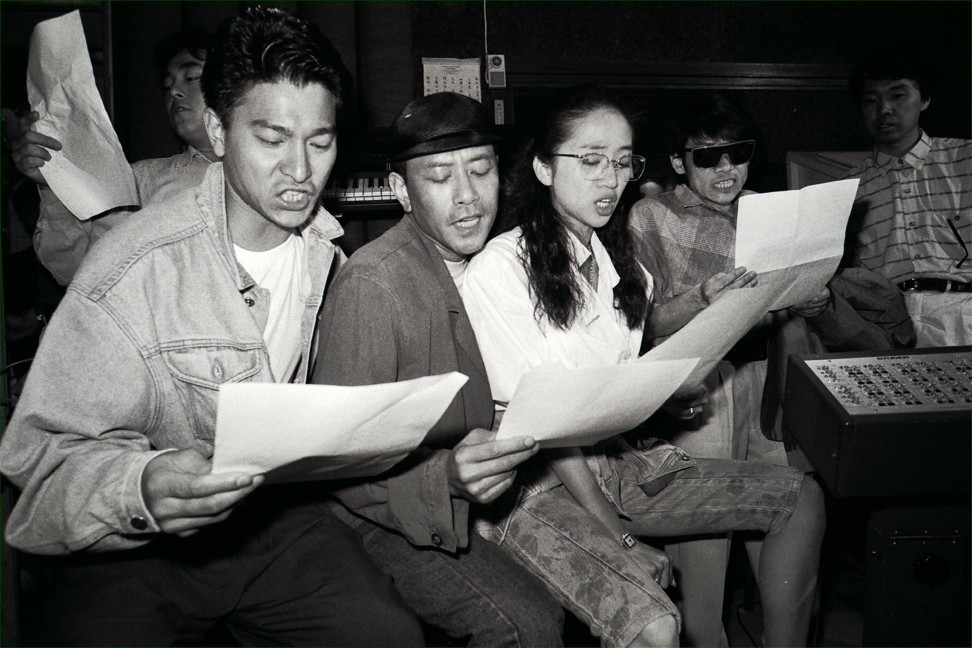

During the “four heavenly kings” era of Canto-pop in the 90s, when Jacky Cheung, Leon Lai, Aaron Kwok and Andy Lau dominated the airwaves, Tam’s attention turned to coaching the next generation of performers. Despite staging a “farewell” concert in 1996, he remained in the public eye and would occasionally play shows or collaborate with other artists.

Leung met Tam through his radio work but grew to regard him as a friend, and remembers his unstoppable energy right up until his final months, when he would spot the ageing star at the raves popular in Hong Kong in the early 2000s.

When Tam died, “it was like the whole city stopped”, Leung says. “Roman is not just a singer. He’s part of our Hong Kong history. He’s the soundtrack of Hong Kong. So losing that is like losing a certain identity of Hong Kong. It was like losing someone from your family.”

Willy Han Zung-nee, who played bass in Roman and the Four Steps, gets choked up recalling the last time he saw his former bandmate and friend, not long before Tam’s death. Han, now 70, moved to Chicago not long after the band split, but stayed in touch with the other members.

“In 2002, I got a call from George Fung [the Four Steps’ guitarist] saying, ‘Hey, you better come and see Roman because he’s got liver cancer.’ So I went and we had a good time.”

Han remembers the band members’ gathering and Fung’s wife, Alice, a seamstress who had created Tam’s early costumes, weeping over Tam’s illness.

“Roman asked her, ‘Why are you crying? I’m the one that’s dying!’ In the end, he was such a good person,” Han says.

But when Han reminisces, his mind goes not to Tam’s dying days but to the concert he watched at Chicago’s prestigious McCormick Place – sometime in the 1990s, though he can’t remember the exact year.

He took his wife and baby daughter, and they were given front row seats. It was the first time he had watched his friend perform since the ’70s and he will never forget the spectacle.

“It was packed,” Han says. “What I saw was a very polished musician; he was world class. Not just his music but his presence. When he walked onto the stage, everybody went crazy. You couldn’t take your eyes off him.”