The history of restaurants, food and, especially, fine dining, is deeply tied to the history of immigration to the U.S. and French cultural power in the early 20th century. Not surprisingly, the story that leads to Yelp and Anthony Bourdain is not without its share of racism that the modern food world and its tastemakers are still grappling with today.

In this episode of The Conversation Weekly, we speak to three experts who study food culture and fine dining about the perceptions and definitions of “good food.” We explore how food trends are deeply tied to immigration, how the history of Western culinary techniques limits the creativity and authenticity of modern restaurants and how social media compares with the Michelin Guide as a tool in the quest for good food.

The definition of ‘good food’

Between ever-increasing culinary skill and creativity, the boom in organic and seasonal ingredients, a growing interest in ethnic food and flavors, and a glut of food media – from the Michelin Guide and Zagat to Instagram and TikTok – there has arguably never been a better time to eat, drink and appreciate a truly good meal.

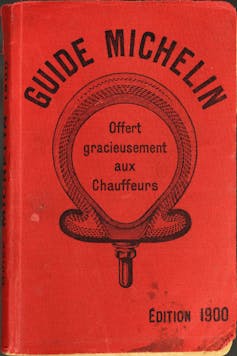

What defines “good food”? This is a subjective question in many ways, but a chef’s career can single-handedly be made or broken by a review in the esteemed pages of the Michelin Guide or The New York Times food section. Even in the world of social media, some restaurants consistently rise to the top of Yelp and Instagram, so there is some consensus idea of what “good food” is.

To understand where the ideas that define good food come from, it’s helpful to understand how the modern restaurant came to be. “At the turn of the 20th century, you have Georges Auguste Escoffier, who, with his friend Ritz, opened the Ritz-Carlton,” explains Gillian Gualtieri, a sociologist at Barnard College in New York City. “The Ritz becomes this training ground for European cooks and chefs, and you then send them out to these glamorous hotels all over Europe to cook for the European and American elites.”

To this day, the techniques and even the language developed by Escoffier are taught in culinary schools across the world.

As the world urbanized, more and more people began to eat at restaurants, and the concept of the food critic emerged. These critics wield power. When Gualtieri asked 120 New York chefs whose opinions mattered most, they most valued the opinions of their peers – and the Michelin Guide.

Immigration and ethnic food

The Michelin Guide and many of its peers in the legacy food media have historically been gatekeepers of fine dining, focusing on white, Eurocentric restaurants and in many ways controlling what kinds of cuisine are worth paying a premium for. But ethnic food – whether it is Mexican, Japanese or, in the past, Italian food – is a massive part of the U.S. food scene.

As Krishnendu Ray, a professor of food studies at New York University in the U.S., explains, the perceptions of immigrant food are closely tied to perceptions of the immigrants themselves.

“What you see is there’s a kind of a early popularity of immigrant foods, first inside the community, and then slowly it spreads outward. Other people start eating, journalists are eating and writing about it, but it does not acquire prestige,” Ray explains. “That changes over time, depending on which immigrant group is coming into the U.S. in the largest numbers and which cohort is slowly moving up in terms of upward mobility.”

After looking at prices of various types of cuisine over the decades and comparing it with immigration trends, Ray found a consistent pattern. Immigrant foods are first considered cheap and not prestigious when lots of immigrants move to the U.S. but slowly gain clout as the people themselves become more culturally established.

Social media influencers as food critics

In an era of social media, many people are now turning to Yelp, TikTok or Instagram to figure out where they want to get a meal. Zeena Feldman is a professor of digital culture at King’s College in London, in the U.K. She was interested in seeing whether Instagram viewed good food in the same Eurocentric ways as the Michelin Guide, or whether, as she explains it, “because anyone can have a voice on Instagram, underrepresented cuisines from different parts of the world and from less expensive price points might be getting more of the attention there.”

To answer this question, Feldman looked at the reviews of Instagram food influencers in London and New York and then compared them with the Michelin Guide.

“Culturally and economically, Instagram food criticism is a lot more inclusive than Michelin,” says Feldman. “So you have many more cuisines, and especially cuisines outside of the Global North, being represented.”

But Instagram wasn’t completely without flaws. “I started out thinking of Instagram food culture as being something created by amateurs, by just people as obsessed with food as I might be,” says Feldman. “What I found is actually these are professionals, either people making money from promoting content or people aspiring to make money from promoting content. And so what that means is that there’s a certain standardization to how food is being represented on Instagram.”

Most people have seen what Feldman has termed the “Instagram gaze.” These are the overhead shots of well-lit food that, Feldman notes, almost never feature any people.

Feldman thinks that, with so much food media out there, there is more opportunity to find good food, but the definition of that, as she puts it, is “food that you actually enjoy eating.”

This episode was produced and written by Dan Merino and Katie Flood. Mend Mariwany is the executive producer of The Conversation Weekly. Eloise Stevens does our sound design, and our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

You can find us on Twitter @TC_Audio, on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email. You can also subscribe to The Conversation’s free daily email here.

Listen to The Conversation Weekly via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed or find out how else to listen here.

Zeena Feldman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Gillian Gualtieri does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. Krishnendu Ray does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.