At the end of the 19th century, long before starting to speak, Pablo Ruiz Picasso (1881-1973) was already drawing – and he grew up “capturing” everything he saw with a pencil.

Through several of the drawings and sketches in pencil made by the young man from Malaga during his formative years in A Coruña (1891-1895), in the North of Spain, we can see clear foreshadowing of what became a revolution that spanned the arts, the limits of perception, communication and expression. The young Picasso’s work was an early form of cubism, an artistic and stylistic movement that officially began in 1907 with the famous painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon – in reference to an old and well-known street in Barcelona with brothels), painted by Picasso.

The fourth dimension (and beyond)

Picasso made cubism official in 1907, but it was something that he had already been able to imagine and begin to represent in some drawings from his time and apprenticeship in A Coruña: the ability to create a new style, a new artistic way of seeing and representing reality.

This made it possible to go beyond the creative limit set by the painters of the Italian Renaissance. They had managed to represent the perfectly consolidated third dimension in a scientific way in Italian Quattrocento paintings – with the first dimension being height, the second width, and the third depth (thanks to the geometric rules of perspective).

Picasso went further and achieved the representation of another three dimensions. He depicted a fourth dimenson – the ability to represent the back – or what is not perceived but what we know is there, for example, the face and the nape of a single character in the same plane.

The fifth dimension (or “depth” dimension) is, for example, the representation of a bare chest with a heart, normally invisible under the epidermis, or the lung. This, in the Renaissance, would have been unthinkable – what was not seen was not represented.

The sixth dimension is the imagined or “dreamlike” dimension. This is what is not there or cannot be seen but what we know exists in the imagination or we have seen in a dream (thus, Picasso was also several years ahead of surrealism).

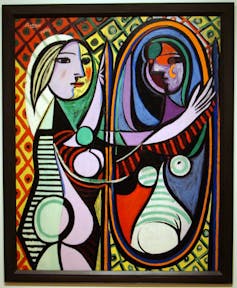

Cubism before a mirror

A good example of these dimensions is the painting Girl before a Mirror, from 1932, which is in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In this portrait of his muse and lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter, we can see the fourth dimension thanks to the face in profile view and the same face in frontal-view. The horizontal black stripes on the left are Marie-Thérèse’s ribs and, therefore, they make reference to the fifth dimension, also present in the representation of a foreshadowed pregnancy in a circumference.

The imagined (or dreamt) vision of Picasso – the sixth dimension – is portrayed in the way in which the mirror reflects an image back at the model of an ugly and decrepit woman who gazes at death. Picasso thus creates an exciting cubist piece with brilliant polychromy.

All this exists and, according to Picasso, can be represented on a single canvas, board or two-dimensional paper.

From the beginning

Picasso was always talented and even unique. He never drew pictures like a child does – “not even when he was very young,” according to his own account. His viewpoint was always adult in nature.

That is why it is so important to revisit Picasso’s drawings from his time in A Coruña (1891-1895). At first glance, they seem just children’s drawings like any others… but they are a lot more than that.

It is necessary to examine them very carefully to truly notice how the birth of a genius came about and how the revolution that was cubism was born. How, from this point on, reality would be represented not always in a hyper-realistic way, as had more or less happened until then, but segmented into geometric, cubic, abstract planes. An incredible turn.

Indicative details

For example, in Double Profile Study of a Bearded Man, the geometric framing of the face is an analytical dissection that surpasses conventional academic work. At first glance, this is an ordinary exercise in the geometric composition of a male face, but the forcefulness of the lines used to mark proportions and the resolute manner of the dark spots (eyebrow, nose, and mouth) foreshadow elements that Picasso will explore further in later cubism.

In Personaje con pipa (Person with a Pipe), the young Picasso incorporates the subtle white chalk technique to artistically accentuate the clothing of the character, as the crossing stripes on the lapel show. Pablo Ruiz was beginning to guide and lead his conceptual way of working towards the adult Picasso.

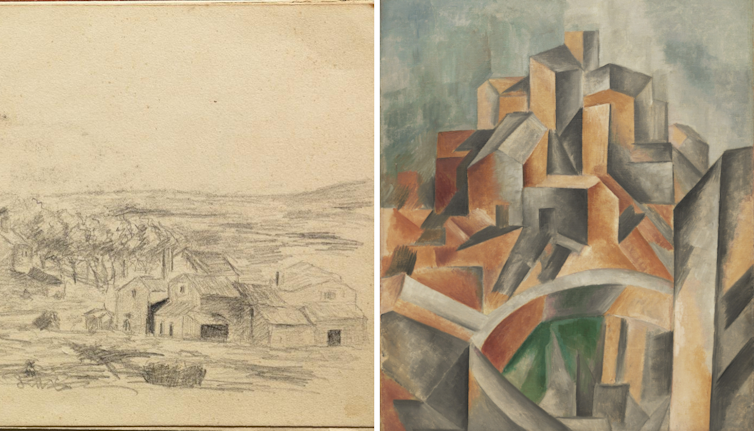

The geometric compositional structure in Caserío gallego (Galician Homestead), elaborated with simple abstraction of space, is related with the rationalist exploration of forms that Picasso would undertake in the 20th century.

In Houses on the Hill of Horta de Ebro, it becomes evident that the geometric and shadow play of this piece had already been foreshadowed in the previous homestead piece.

Obviously, it cannot be said that there are glimpses of forms that point towards the Cubist revolution in all the drawings from A Coruña.

But, if the previous pieces and some others are observed, we will see that something of what was to come was beginning to take shape in the Galician city.

Ximo Company i Climent does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.