What was once a vaunted and ambitious project now looks closer to a mill stone around the neck of prime minister, Rishi Sunak, and his government.

Is HS2 in trouble?

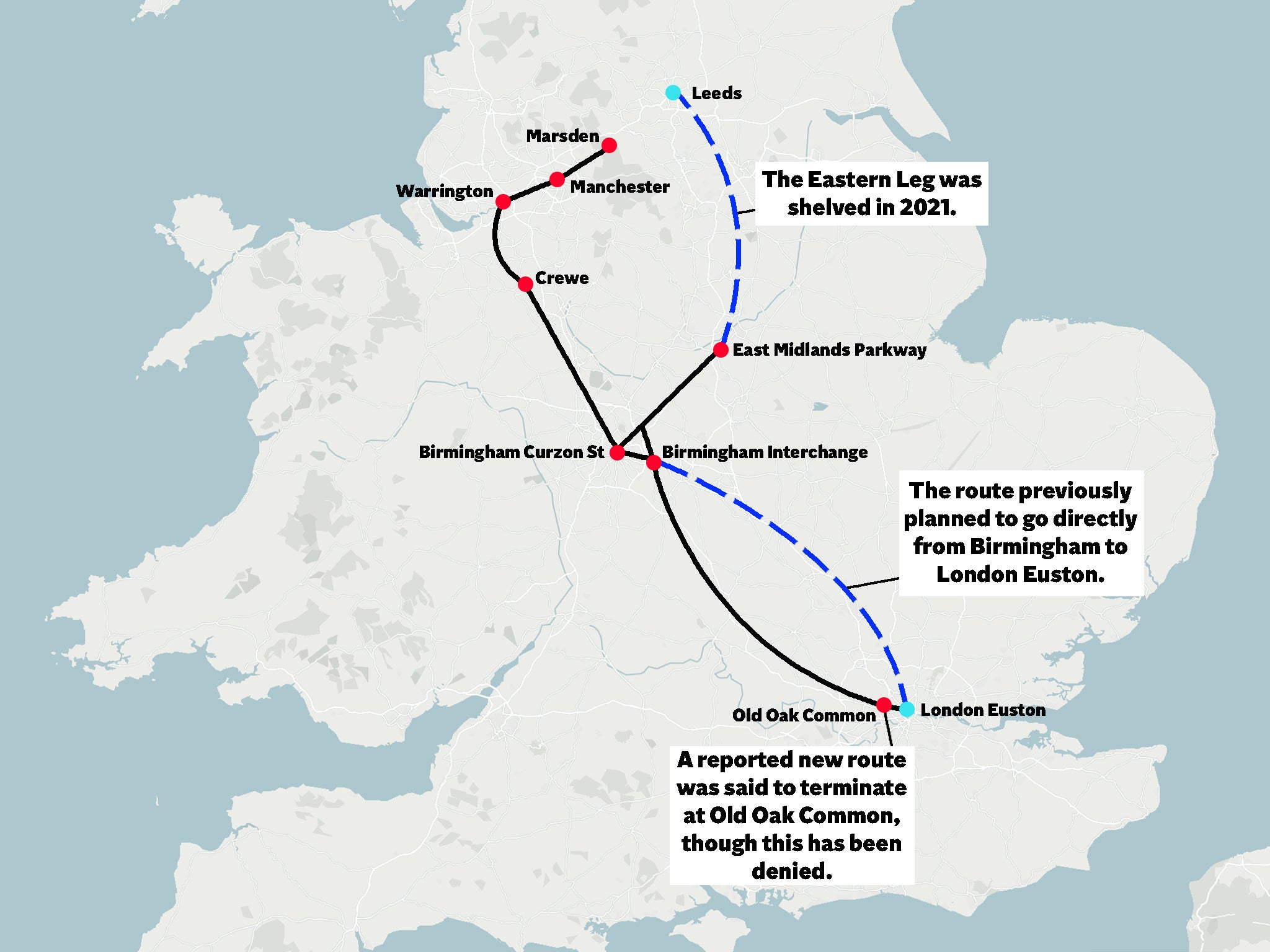

Yes. Again. Reports suggested a radical downgrade in its pace and/or ambition on the grounds of rapidly escalating costs - labour and materials after Brexit, post-pandemic disruptions and the Ukraine war ramping up the price of energy. Various options have apparently been discussed in government. These include any permutation of: ending the line in the west London suburbs instead of Euston mainline station; not extending the line north of Birmingham to Manchester; or pressing on with all or sort of the project but at a slower pace, taking completion from 2033 to nearer to 2040.

What have the government said?

The chancellor, Jeremy Hunt was first to voice a denial of the story, which appeared in The Sun. He said that he couldn’t see “any conceivable circumstances” in which HS2 would not run to its planned central London terminus at Euston, and added that he’d put the funding in the Autumn Statement last year. However it is not clearer whether that funding is in some sense inflation-proofed, and Hunt failed to say when the link to Euston would be completed.

Later on, Sunak gave a similar interview, but again didn’t volunteer any view on timings. The prime minister also started talking about how HS2 shouldn’t get in the way of local rail upgrades, “in the here and now” suggesting that such a re-ordering of timings and priorities is exactly what’s being discussed in government circles. Sunak may be looking for a more rapid political payback from transport projects this close to the election

What would happen if the route was snipped?

The project would go into a kind of downward spiral, and lose its point. Ending the line at Old Oak Common in west London would mean fewer platforms and thus fewer trains and fewer passengers and lower revenues – as well as being a less attractive prospect for passengers. Removing a strong passenger flow from Manchester, Lancashire and North Wales, via Crewe, would also harm financial viability.

But hasn’t HS2 been troubled for some time?

It has been almost from the moment it was invented in the dying days of the last Labour government, and then taken up enthusiastically by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, and championed by then chancellor George Osborne as part of a mission to revitalise the North and Midlands, together with an enhanced East-West link across the Pennines. Boosting both the “Northern Powerhouse” and “Midlands Engine”. The HS2 legislation was passed in 2013.

At first it was a very ambitious project. The coalition ministers were like overgrown school kids with a giant Hornsby set. The “Y” shape concept comprised two branches out of Birmingham. The north west route was to go via Manchester and then join up with the West Coast Main Line for Glasgow and far into Scotland. The north east branch would connect with the Midlands Mainline and East. Islands, and then on to Leeds, Bradford and then link to the East Coast mainline and Newcastle. There was even a scheme further to cross London and add links to Heathrow and with HS1, and thus Paris, Brussels and Amsterdam

Now, after successive reviews and cuts, only Manchester and the East Midlands spurs survive. Probably.

What was the original point of HS2?

It was often derided as merely cutting a few minutes off a journey to London; but the real benefit was to be in increasing capacity on overcrowded routes. Connecting and boosting isolated economies, and creating new busier and enhanced commuter lines outside the south east.

What about the political benefits?

The original project would have potentially proved a substantial boost for the Conservatives. It would have proved their commitment to “levelling up” the regions, and make people in and around great cities such as Leeds, Bradford and Newcastle think more warmly of voting Tory. It would have helped them hold “red wall” seats, even if it was years away. Now it has caused some considerable disappointment in Yorkshire and beyond.

Is there now a political price?

Yes. In suburban and rural seats across the Home Counties and the West Midlands was there was and is much local opposition, adding to general concerns about the green belt and overdevelopment. Environmentalists also object to the loss of habitats and ancient woodlands. The loss of the safe Tory seat of Chesham and Amersham to the Liberal Democrats in a by-election last year was one example of an electoral backlash in the “blue wall”.

Some Tory backbenchers would rather the total cost of £150bn plus be devoted to tax cuts or other public spending. Others favour the creation of a piece of strategic national infrastructure that will last decades if not centuries, like the Victorian railways and Roman roads. Short term political time horizons clash badly with long term economic ones.