Tour de France mountain stages are brutal, no matter how fast you’re riding them. But, they're made even more challenging by the dreaded time cut, a limit Mark Cavendish narrowly beat on stage 14 of the 2024 Tour de France, crossing the line with 1 minute 47 seconds to spare.

The race's Queen stage - stage 19 on Friday 19th - looks set to be another battle against the clock for the sprinters.

But how does the time limit actually work?

The most decisive stages in the French Grand Tour are often even tougher for those struggling at the back of the race than they are for the climbers going full gas at the front.

Varied nature of the stages on the Tour de France route are what makes cycling great, with each day suiting either the sprinter, the climber, the puncheur, the time trialist, the breakaway specialist - but never all five at the same time.

Mountain stages are unsurprisingly best suited to the sinewy, lightweight climbers who are able to maximise their watts per kilogram to get over the steepest gradients.

These riders are often battling for stage wins on famous climbs like Alpe d’Huez and Mont Ventoux, or are desperately clinging onto their general classification times and trying to avoid any time losses as the road turns towards the sky.

But for the heavier riders, particularly the sprinters, every mountain stage is its own hazard, as they face threat of elimination from the Tour de France if they aren’t able to finish the stage within the time limit.

If you’ve ever seen riders at the bottom of the results with the letters OTL (outside time limit) next to their name, you may wonder how and why.

The time limit exists essentially to keep things fair across the Tour de France, so riders can’t finish hours behind the stage winner in order to recover more, giving them an advantage over rivals who may have ridden harder consistently.

Cycling Weekly has taken a dive into the rule book to explain the complicated time cut system at the Tour de France

How do Tour de France time limits work?

The UCI rule book actually has very little detail about how time cuts work.

Under regulation 2.6.032 covering stages races the rules state: “The finishing deadline shall be set in the specific regulations for each race in according with the characteristics of the stage.

“In exceptional cases only, unpredictable and of force majeure [unforeseeable circumstances], the commissaires panel may extend the finishing time limits after consultation with the organisers.

“In case riders actually out of the time limit are given a second chance by the president of the commissaires panel, all points awarded in the general classifications of the various secondary classifications shall be withdrawn.”

In short, it’s up to the race organisers to decide the time cut based on how difficult a stage is.

The race jury is allowed to let riders to continue even if they finish a stage outside the time limit, but only in exceptional circumstances.

This actually happened in the 2018 Tour on the short stage 11 to La Rosière, won by Geraint Thomas.

A number of the best sprinters were eliminated, including Mark Cavendish and Marcel Kittel, but Rick Zabel was allowed to continue the race, despite finishing three seconds outside the limit.

Zabel was allowed to continue because he had suffered a mechanical on the final climb, which prevented him from making the limit.

For any riders allowed to continue the stage race after being outside the time limit, they must forfeit any points they scored in the King of the Mountain or the points classification during the entire race - this prevents riders attacking hard early on the stage to score points and then deliberately dropping back to recover more than their rivals.

How the time cut is calculated?

The time limits for each stage are set by the organiser of the Tour de France, ASO, and must be set out in the ‘Road Book,’ which is the detailed guide to each stage released before the race starts.

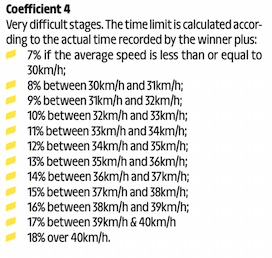

For each stage, the first thing the organisers need to do is decide the difficulty of each stage, by giving it a score from one to six, also known as the coefficients.

After deciding the difficulty of a stage, the time cut is then decided by how fast the stage winner actually rides the stage, using their average speed as the benchmark.

So for example, on a stage with a level one difficulty, if the stage winner rides at an average of 36km/h or less, the time cut is set at four per cent of the winner’s time.

But on the same stage, if the winning rider holds an average speed of 50km/h, the time cut increases 12 per cent.

The time cut then extends as the stages get more difficult, the riders are allowed to finish seven per cent slower than the stage winner if the speed is 30km/h or less, all the way up to 18 per cent if the speed is over 40km/h.

ASO also has its own rules for reinstating riders who are outside the time limit, as the race jury has power to allow a rider to continue even if they don’t make the time cut.

The rules state: “The commissaires’ jury may in exception cases allow one or several particularly unlucky riders to be reinstated in the race, after informing the race directors.”

But the jury must consider four factors when reinstating a rider - the average speed of the stage, the point at which the accident or incident occurred (if there was one), the effort made by the delayed riders, and any possible blockage of the roads.

There is one particularly memorable case of riders being reinstated after finishing outside the time limit in the 2011 Tour, when Mark Cavendish was among a group of 88 riders who finished outside the time limit, but were later reinstated by the race jury. Under today's rules, Cavendish would have been stripped of all of his green jersey points for finishing OTL, and most likely would not have won the jersey.

He was also docked 20 points in the green jersey competition, which he was still able to win. In the 2016 Vuelta a España, 93 riders also failed to make the time cut on stage 15 only to be allowed to continue.

It was a brutal 118km stage, raced at an average of 40km/h and lasting just two hours and 45 minutes.

But by the finish, the main peloton of 93 riders finished outside the limit of 31-24, with the group finishing in 52-54.

The jury decided to reinstate all of the riders, so the race didn’t have to continue with just 71 riders remaining.