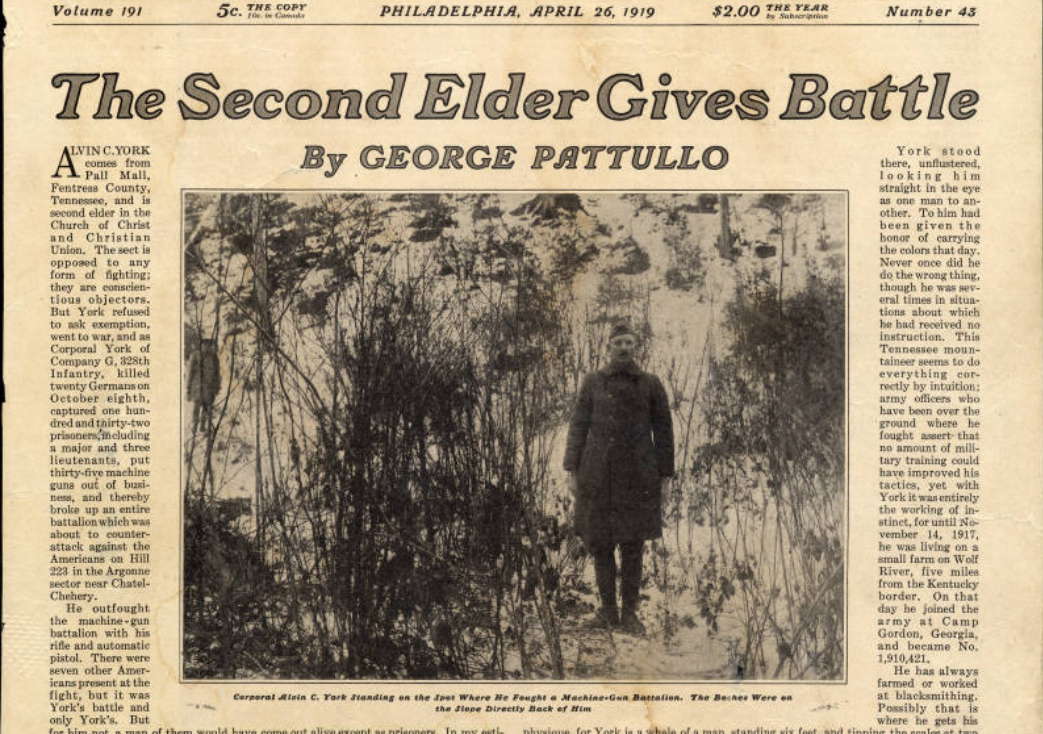

On a quiet walking path on the outskirts of an idyllic French village in the country’s north Argonne region stands a monument.

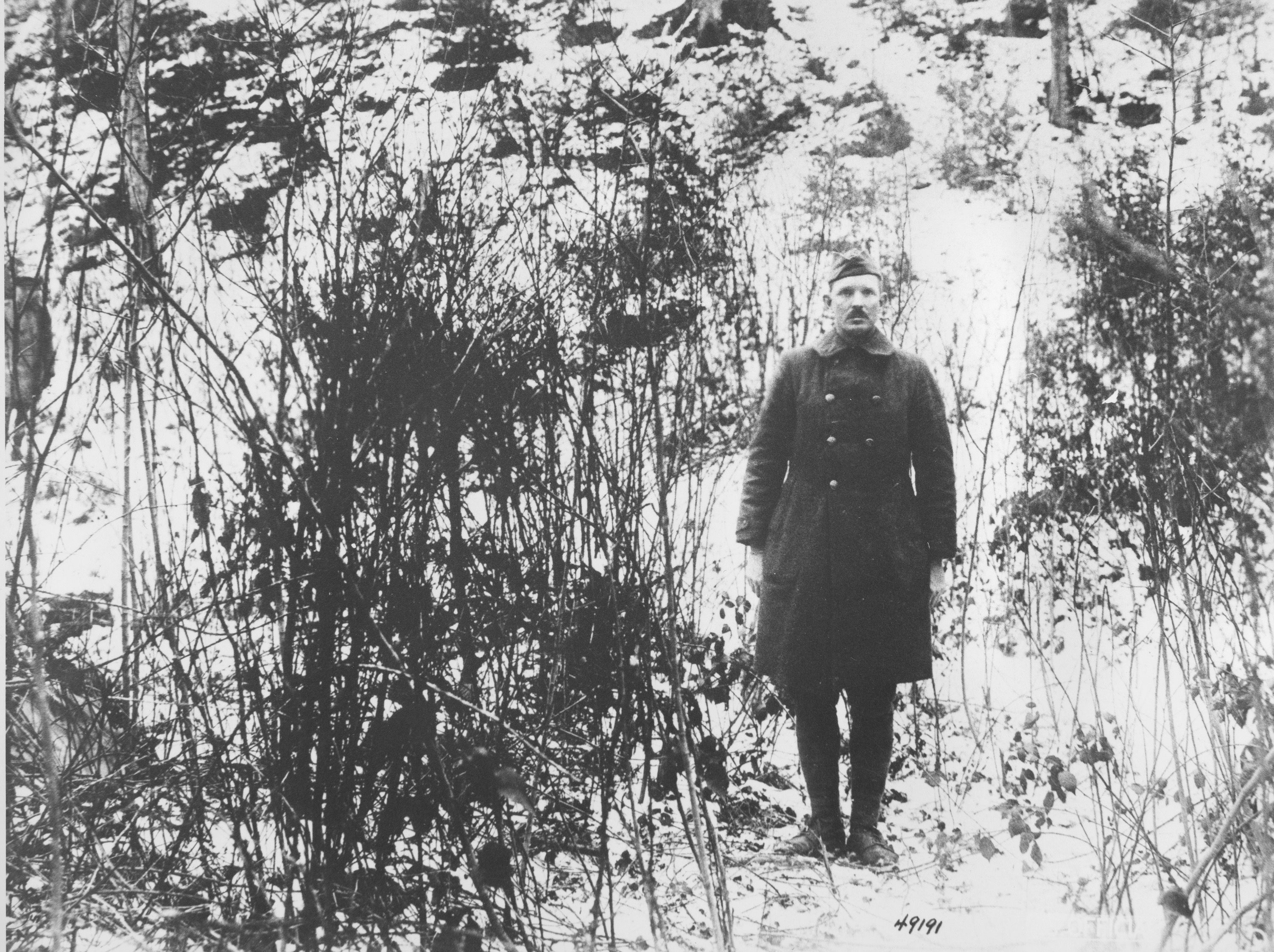

The accompanying plaque notes that it’s the precise location where Sgt Alvin York single-handedly picked off 20 to 25 German soldiers on 8 October 1918. The Tennessee-native would go on to capture 132 more as prisoners in an act of bravery that later earned him the rarely bestowed Medal of Honor. All while only armed with a rifle and pistol.

Translated into English, French and German, the sign lends a sense of authority to the notion that the site where one of the “greatest achievements” carried out by an Allied soldier during the Great War is a settled fact, and not one up for debate.

That is, of course, how the sponsor of the tourist attraction and its accompanying signage described it when his crowning achievement was unveiled to the public in 2008.

“The debate is over,” proclaimed Doug Mastriano, then only a little-known Lieutenant Colonel in the US Army.

That conjecture, which would go on to form the foundation for the now-Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate’s PhD dissertation, has faced an onslaught of challenges from Mr Mastriano’s many critics in the years since.

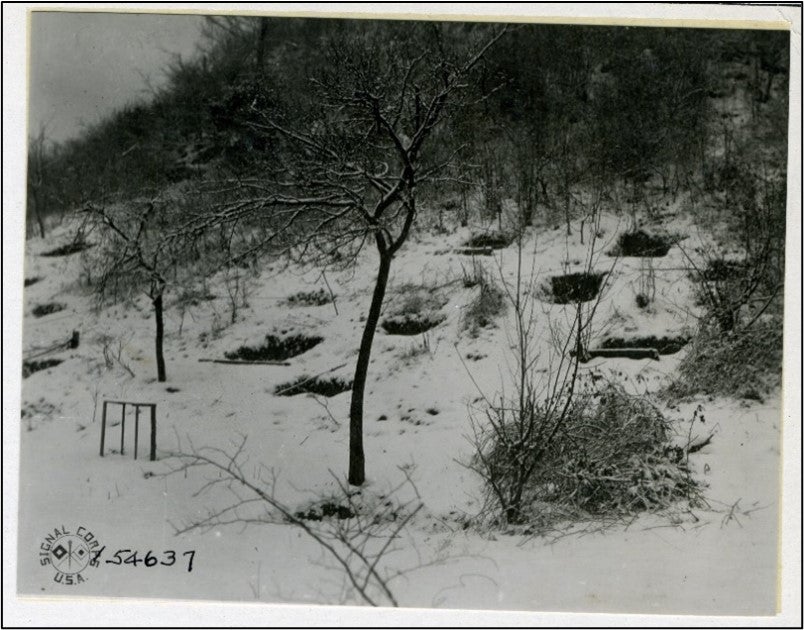

Academics in the fields of history and archaeology maintain that the Republican’s research methodologies were flawed from the start. Mr Mastriano’s proposed site of the York’s battle sequence is not only wrong, but 600 metres north of where it actually played out.

Further, his critics argue that other work he’s put out on the same topic, specifically his doctorate-earning thesis from the University of New Brunswick and book published with the University of Kentucky Press, has granted him both unearned authority to his problematic conclusions and even altered the record of history.

“Anyone who ever uses Mastriano as a source, their work is tainted, because he’s literally changed history away from the documents and the facts to fit his own theory,” said James Gregory, a doctoral candidate at the University of Oklahoma, in an interview with The Independent earlier this month.

And it’s not just Mr Mastriano’s work as a historian that’s been called out for allegedly moulding narratives to fit his own personal – and political – persuasions. His pursuit of righting the academic history of Sgt York seemed to presage his own race for the Pennsylvania governor’s mansion.

In the months before and after announcing his candidacy for governor, the GOP hopeful has acted as a megaphone for spreading Donald Trump’s Big Lie, taken to social media to amplify QAnon conspiracy theories and dispersed misinformation about Covid-19 all while sitting as an elected official in Pennsylvania.

Should he win in the November midterms, the election-denying candidate has indicated he also plans to upset the very democratic process that made him a state senator.

“I get to appoint the secretary of the state, who’s delegated to…making corrections to elections, the voting logs and everything,” he said in the springtime. “I could decertify every machine in the state with a stroke of a pen.”

In the political domain, Mr Mastriano has faced few repercussions for his tendency to bend the truth. In the academic world, owing greatly to the unrelenting scholarship of 27-year-old historian Mr Gregory, Mr Mastriano may get his due.

After filing a secondary report that documents more than 200 instances of academic fraud, Mr Gregory’s due diligence has prompted UNB to reckon with one of their more notorious graduates in recent years. It announced earlier this month that a two-member panel of independent academics will carry out an investigation into Mr Mastriano’s work.

Though it could be the most consequential instance of his skullduggery being flagged to the school, it’s hardly the first time that Mr Mastriano has been put on notice by the academic community.

A history of issues

Mr Mastriano’s work digging in the French countryside and inking papers on Sgt York had been the preoccupation of York-aficionados in the field for years before Mr Gregory fired off an initial report in early 2021.

One of Mr Mastriano’s rivals in the York debate, Dr Thomas Nolan, began pushing back on the site’s legitimacy as early as 2007. Then, the NATO officer declared that he’d uncovered the original site of the famed battle.

Dr Nolan, geographer and head of the Laboratory for Spatial Technology at the University of Middle Tennessee, led a competing group of academics and specialists, who called themselves the “Sergeant York Project”. While relying on his specialty of applying Geographical Information Systems (GIS) to military history, Dr Nolan and his fellow SYP’s deduced that his site, lying about half a mile away from Mr Mastriano’s, was more likely the one for where the battle took place.

“It’s absurd to say that you’re a hundred percent sure of yourself. A scientist may never claim to know the absolute truth,” said Dr Nolan in a 2009 article criticising Mr Mastriano’s confidence. “Our team was the only one with a permit for archaeological research. In fact, you could say that Mastriano’s expedition was illegal,” added the geographer.

Others in the field continued to share their misgivings about his work. Archaeologist James Legg, who contributed to Dr Nolan’s dig in 2009, described Mr Mastriano’s dig as “convincing material for the uninitiated” but that it ultimately resulted in an “unsystematic” and “unauthorized relic hunt”.

Concerns were reupped in 2012 in a pair of papers published in the Winter 2012 edition ofTennessee Historical Quarterly. Dr Nolan and military historian Brad Posey, who also worked on the 2009 dig, enumerate the many ways in which Mr Mastriano’s archaeological work was not only incorrect, but how he actually “caused irreparable damage to the site.”

The pair of academics would even go on to flag their issues about Mr Mastriano’s research to UNB in 2013, claiming his research was flawed and contained cases of academic misconduct.

Those early warnings went ignored. A year later, the veteran’s book on the topic, which was, per UNB, his “dissertation largely unchanged”, would be published with the University of Kentucky Press.

Mr Mastriano, for the time being, would be safe from scrutiny -- until the work of a young historian, interested in the same fabled military figure, would begin to pull at the threads of his not-so-well spun yarn.

‘35 instances of academic fraud’

The relationship between Mr Gregory and Mr Mastriano hadn’t always been an icy one. Mr Gregory admits that he was actually in direct contact with Mr Mastriano, mostly via Facebook DMs, when he was researching his own book on the famed sergeant (which itself attempts to decipher the messy past around Sgt York’s 328th Infantry Regiment, aptly titled Unraveling the Myth of Sgt. Alvin York).

“We had a cordial relationship or at least he would answer my questions in detail. That is until he found out that my work countered his,” said Mr Gregory. “And then he stopped talking to me.”

In early 2021, he began compiling a report on Mr Mastriano’s work. Though, he was unable to put it under the full magnifying glass as the 500-page thesis in question was under embargo till 2030.

Having only the book to work off of, Mr Gregory managed to unearth 35 instances of academic fraud. These findings were then sent to the University of Kentucky Press and then later, Dr David MaGee, the then-acting vice-president of research at UNB.

The first institution responded by informing the graduate student that his inquiries would be taken seriously.

In a recent email, the director of the press confirmed that they’d sent Mr Gregory’s initial queries to Mr Mastriano regarding citations in his book Alvin York.

“Some of these queries include simple confirmation of typos while others require the author to provide additional sources to confirm specific information in the book,” wrote Ashley Runyon, adding that they carried out their own comprehensive review of the author’s responses and original primary sources to verify its accuracy.

“This information will be used for future printings of the book to correct any errors. Our review has been independent from the author. Any potential changes were shared with the author, but the final decision will remain with the Press.”

While UNB released a report to him in April of that year which dismissed the allegations as nothing more than unintentional technological errors.

“I have reviewed the results of the inquiry and have determined that this allegation does not require a formal investigation,” said Dr MaGee in an email dated 3 April 2021, which Mr Gregory shared with The Independent. The “irregularities” in quotations, he added, were the result of a transcription error. “There is no misrepresentation or intent to deceive, but an honest error, which we will have corrected through a corrigendum to the copy of the PhD thesis.”

Mr Gregory concedes that some of the original 35 errors raised could be described as being transcription error, but 20 instances, he maintains, are still “fraudulent”.

“That means that left 20 of my original 35 that were blatant cases of fabrication,” said Mr Gregory, who says that when he pushed back on Dr MaGee about this, the line went cold as the school maintained that the rest were “up for academic debate”.

“This is not James Gregory vs. Mastriano. This is Douglas Mastriano vs. his own sources. This man is lying about these documents and passing them on,” said Mr Gregory.

Without access to the original dissertation or the school addressing his earlier concerns, Mr Gregory was left to wait in the wings.

‘213 is beyond a reasonable doubt’

While that initial report was the subject of many headline-grabbing reports, it wasn’t until this past fall that the university announced they’d be tasking two independent academics with reviewing Mr Mastriano’s thesis.

That is largely because Mr Gregory had the opportunity to sink his teeth into the Mastriano dissertation ahead of its 2030 embargo and submitted a secondary report outlining more than six times the original figure of academic fraud he accounted for.

“213,” he says, with a humble concession that this was just based on his first run through the text. There could, and likely are, much more, he adds.

“Thirty-five examples were a questionable amount, but now 213 is beyond a reasonable doubt,” wrote Mr Gregory in that follow-up report emailed to Dr MaGee and other faculty members from the institution’s history department on 6 October. “Mastriano’s work is fraudulent.”

Included in that damning secondary report are stunning examples of Mr Mastriano’s flippancy with sourcing, outright instances of forging evidence to fit his own chronicle of history, academic dishonesty and multiple examples of fabrication.

Mr Mastriano cites a source that remarks 12 soldiers, when Mr Gregory notes it was actually five. Mr Gregory writes in the report that Mr Mastriano misquotes and fabricates sources, allegedly in multiple instances, to fit his own narrative.

One of York’s comrades, Private Percy Beardsley, “freely discussed York but did not describe his own central role in the battle,” wrote Mr Mastriano, a claim that supported his narrative that York “single-handedly” killed more than two dozen Germans.

“Fabrication,” writes Mr Gregory in the next sentence. “Neither of the cited pages even mention Beardsley or his statements.”

A litany of bolded “fabrications” litter the report, which Mr Gregory went through the pains of fact-checking nearly all footnotes cited by the state senator. Of the dozens of examples listed, perhaps the most egregious of them all is one where Mr Gregory pinpoints how Mr Mastriano doctored a photograph and caption from a different document to artificially support his argument that he found the York site.

“That description is from another photograph,” the PhD candidate told The Independent while going through the report. “So he’s making it up. He’s just collaged two different things to make something look like he’s arguing his case.”

Dr MaGee confirmed in an emailed statement to The Independent that the university had received Mr Gregory’s second report and would be following the school’s policy when it came to dealing with allegations of research misconduct.

He added that, due to the Right to Information and Protection of Privacy Act, the school is not permitted to “discuss the personal information of our students, including educational information, whether the student is a public personality or not, without the student’s consent,” which would include Mr Mastriano.

The Independent has approached Mr Mastriano for comment but he didn’t respond before publication.

The fallout

On 6 October, after months of media coverage on Mr Mastriano, UNB put out a statement.

“UNB has a clear policy for dealing with any allegations of research misconduct,” it said. “UNB will review its internal processes to ensure our systems and policies around the awarding of PhDs remain of the highest standard,” it added, noting that the review would be carried out by two independent academics.

No timeline or whether those results would be made public was announced. The Independent contacted the institution to inquire about those specifics but did not hear back.

For some inside the university, addressing the problems within Mr Mastriano’s work is arriving many years too late. Dr Jeffrey Brown, a history professor at UNB, sat on Mr Mastriano’s examining board for his dissertation back in the early 2010s. Even then, he told The Independent, he was taking issue with the then-PhD candidate’s squaring of the truth.

“There are all sorts of problems with it. It troubled me then and it continued to trouble me for years,” he said in an interview earlier this month, just days after the second Gregory report had dropped in the inboxes of UNB staff.

Dr Brown, similar to Mr Gregory, raised those concerns with other members on Mr Mastriano’s dissertation board. He spoke with the dean of graduate studies, flagged the issue to the associate dean and even contacted Mr Mastriano’s supervisor, Dr Marc Milner.

“I did everything I could to try to flag problems with it, which were multiple and glaring, and was pretty much ignored, and then eventually kind of pushed aside,” he said.

Dr Milner did not respond to The Independent’s request for comment.

After final drafts of the thesis were presented for defence, Dr Brown realised that the issue of Mr Mastriano’s research – which initially hadn’t even mentioned the multiple academics who had taken issue with his archaeological work or discussed the competing York site – wasn’t going to be settled to his standard.

“It’s totally irresponsible scholarship. And it’s not credible as a PhD thesis,” he said.

In an email to Dr Milner from 2013, which the history professor shared with The Independent, he expresses his concerns and asks that he be removed from Mr Mastriano’s board.

That was amenable, Dr Milner informed him, as he wasn’t needed to sign off on Mr Mastriano’s final defence.

“Thank you for your help and see you later,” said Dr Brown, relaying what was said to him back in 2013. “So, that’s how the thing got passed.”

That spring, the now Republican nominee in Pennsylvania’s governor race received his doctorate from UNB without issue.

Now, with Mr Gregory’s report drawing attention, the school has announced their first public – and independent – inquiry into the issues first raised by the PhD candidate in 2021 and his predecessors, including Dr Brown, many years before.

“Certainly no one here was qualified to assess the archaeological part of [the thesis],” said Dr Brown, acknowledging that it made up about 40 per cent of the finished product. “Depending on the results of that investigation, the university ought to be prepared to rescind Mastriano’s degree.”

Dr Brown noted that, while he hadn’t read Mr Gregory’s report in full, Mr Gregory’s in-depth examination of sources should’ve been done years before by his own supervisor.

“But if he’s right, this guy got his PhD fraudulently,” he said. “And he shouldn’t have it.”

For their part, the university hasn’t indicated when, or what, will be released from the probe. And as Mr Mastriano’s political star has risen, so too has the spectre that’s been placed on UNB as pollsters and reporters clamour for the latest update on a man who could be the next governor of a major swing state in the 2024 election.

And while his aspirations to rewrite the rules of modern-day elections have yet to come to fruition, it’s now incalculable to measure the damage he may have done to the historical record of one of the First World War’s most fabled veterans.

“Basically, he comes up with the answer, and then tries to make everything fit to that final answer,” says Mr Gregory, alleging that Mr Mastriano has “polluted” the record of Sgt York with his “falsified research”.

“He wants everything to fit and if anything falls outside of that, he’ll call them ‘detractors’ or says, ‘it’s false information, don’t worry about it’.”