One species of iconic moa was almost wiped out during the last ice age, according to recently published research. But a small population survived in a modest patch of forest at the bottom of New Zealand’s South Island, and rapidly spread back up its east coast once the climate began to warm.

What we’re learning about this remarkable survival story has implications for the way we can help living species adapt to climate change, and how we conserve and restore what may be important future habitats.

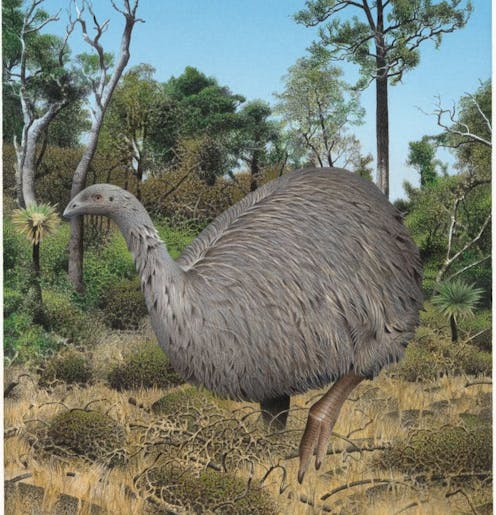

Growing to around 80kg and up to 1.8 metres tall, the eastern moa was one of the smaller of the nine extinct moa species. It got its name because its fossil bones have been found in sand dunes, swamps, caves and middens all along the eastern parts of the South Island – Southland, Otago, Canterbury and Marlborough.

Eastern moa became extinct from over-hunting and habitat destruction by humans, and possibly predation by kurī (dogs) and kiore (rats). But were eastern moa populations thriving when people arrived, or were they already in trouble due to ancient climate change?

Refuge in the south

Between 29,000 and 19,000 years ago, New Zealand was in the grip of an ice age. Glaciers were much larger and more widespread than they are today, and the distribution of grasslands and forests changed as the climate became colder and drier.

Current climate change threatens the survival of many different species, and the same was true of climate change thousands of years ago. The fossil record hints that the ice age was bad news for eastern moa, as few eastern moa bones from this period have been discovered.

But a lack of fossils doesn’t necessarily mean a species was doing it tough. Perhaps they just avoided the caves and swamps where we might eventually discover their bones.

Read more: How a change in climate wiped out the 'Siberian unicorn'

To find out more, we sequenced DNA from dozens of eastern moa bones to see how their genetic diversity and population size changed over the past 30,000 years.

Large and healthy animal populations tend to have high genetic diversity, while low genetic diversity can be a sign that a population is in decline. We found eastern moa had very low genetic diversity immediately after the last ice age.

So eastern moa didn’t cope well with the ice age climate – but how did they manage to escape extinction? Our study provides a clue: their genetic diversity was highest in the very south of the South Island.

Preserving future habitats

During the ice age, grassland replaced wet podocarp forests in many areas. Those forests were the favourite habitat of eastern moa, possibly explaining why they struggled to survive.

Luckily for eastern moa, however, small pockets of forest survived in southern New Zealand during this time. While eastern moa disappeared from most of the country, our study suggests they clung on in remnant forest at the very south of the South Island.

Scientists have a special name for pockets of habitat where species can shelter and endure climate change – “refugia”.

Read more: How the warming world could turn many plants and animals into climate refugees

Once the climate began to return to pre-ice age conditions, eastern moa were able to return to parts of the country they had formerly occupied. They bounced back so well that they were the most common moa in some parts of New Zealand at the time of Polynesian arrival.

Ancient DNA from fossils across the world has shown that refugia play an important role in allowing species to adapt to climate change. The story of eastern moa shows this is equally true in New Zealand.

Importantly, though, the eastern moa was affected differently to other moa, showing not all species are affected by climate change in the same way. Our study emphasises the need to conserve and restore a diverse range of habitats for the future, given the places where species are found today may be unsuitable for them in the very near future.

By ensuring that species can continue to find appropriate refugia, we may reduce the number that become extinct as a result of our global impacts on the climate.

Nic Rawlence receives funding from the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund.

Kieren Mitchell receives funding from the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund.

Alexander Verry does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.