On a cold, wet November morning, Joe Luzzi stepped out of his house thinking he knew exactly where he was going: to the university, where he was a professor of Italian studies and had students to teach. What he now knows, seven and a half years on, is that he was in fact striding into what the medieval poet Dante described in The Divine Comedy as the dark wood, the bleakest experience of his life – and that he would be lost there for a long time.

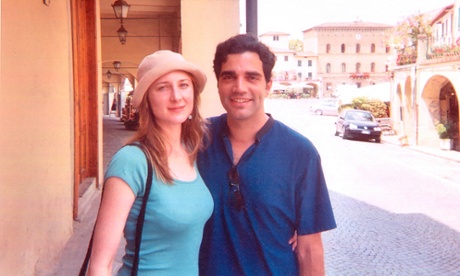

As Joe left home that day, he kissed his wife, Katherine, goodbye, confidently expecting to have supper with her later, when they would doubtless chat excitedly about the imminent arrival of their first child. But that never happened because, a few hours later, Katherine was killed in a car accident. The doctors who tried to save her failed: but they did manage to rescue, by emergency caesarean section, the couple’s daughter, Isabel. “I left the house at 8.30am,” says Joe. “By noon I was a widower and a father.”

Joe, 47, is the son of Italians who emigrated to the US: he was their first American baby and he spent his early life determined to break out of what he calls the Calabrian village in which he was raised, an outpost of his parents’ original homeland recreated in upstate New York. He had been successful, worked hard, moved away: but now, in the middle of the wood in which he found himself, he realised he had to fall back on his family, especially on his elderly, widowed mother, Yolanda, to help him raise Isabel.

“My mother had spent her life caring for people,” he says, “and straight away it was clear she was ready for this, ready to care for her motherless granddaughter.”

But over the next few months and years, while Yolanda was nurturing the baby, someone else was nurturing the grieving father – a writer who lived 700 years ago: Dante Alighieri, author of The Divine Comedy.

Dante had been central to Joe’s academic career but until Katherine’s death he had only experienced him as a scholar and an admirer. “Now, for the first time, I identified with him in a visceral way,” he says. “After Katherine died, I turned to books about death and loss but nothing I read really spoke to me: until I realised that Dante had experienced exactly what I was going through. His muse, Beatrice, dies, and she becomes his guide in The Divine Comedy. He lost his great love and I lost my great love. Where Dante truly spoke to me was where he writes about exile: in the middle of life’s journey, he says, I found myself in a dark wood.

“He was a guy who had everything: he was a leading poet, a politician, he was living in one of the most exciting cities in the world and then suddenly he was kicked out and defamed. For the last 20 years of his life, he wandered around Italy, banished from his beloved Florence. That’s exactly what the loss of my wife felt like: I felt I was being banished from the life I was expecting to have, cut off from it just at its most wonderful moment.”

The university offered compassionate leave, but Joe realised that his salvation lay in work. So he carried on reading, writing about and teaching Dante, while his elderly mother, aided by his four sisters, cared for Isabel. It was far from ideal, he says now, because he couldn’t connect with his child as he wished he could have done. But she was fine: his 76-year-old mother may have been drawing on an experience of parenting that had its roots in Calabria in the early 1950s, where she bore Angelo, the first of her six children, when she was only 17; but she knew that babies need love and devotion, and in Katherine’s absence stepped in to provide it.

But that was for Isabel: for Joe, the story was different. He was now a grieving man living in his teenage bedroom in his childhood home; and when his baby woke in the night it was her grandmother who would attend to her. Yolanda wasn’t shutting him out: she was simply putting Isabel first, meeting her grandchild’s deepest needs. But as the weeks turned to months and years, it was clear that her ways were very different to Joe’s and Katherine’s.

Instead of organic food and additive-free snacks and limited screen-time, Isabel was being raised on fast food, jelly, trips to the shopping mall, and an overdose of Dora the Explorer.

One of the hardest things, says Joe, is for him to admit that he made mistakes as a father. Now, though, he can see that he buried himself in his work when he really didn’t have to toil away quite so hard, and when he could have been more present for Isabel. And it was that realisation that he would have to become his child’s father – properly her father – that was to lead him out of the wood. That and the discovery, again led by Dante, that in order to move on with his life he had to accept what he found impossible initially to accept, which was that Katherine was dead, and that life never would and never could be the way it was going to be, either for him or for their child.

“I realised I had to let the person I was, or at least a part of him, die along with Katherine, and then I had to build a new life,” he says. “What happened to Dante, you see, was that in the midst of his greatest defeat, he created something beautiful, something he would never have been able to create if he’d stayed in Florence: he wrote The Divine Comedy.”

Eventually, Joe began dating again and an extraordinary thing happened – the woman with whom he got into a relationship had a life that almost mirrored his own. Her spouse was also dead and she, too, had an infant daughter (she used their frozen embryo to have his baby after his death from cancer). “It was eerily similar, and I thought it would work perfectly,” he says. It didn’t.

Joe was always clear that any relationship he might have must work not just for him, but for Isabel. So when an English musician named Helena arrived in his life, he knew that the most important test would come when Isabel, then three, met her for the first time. That introduction was, he says, the most momentous of his life. Luckily, it went well, and even though the following months brought some turbulent times as Isabel struggled to adapt to a life without her beloved Italian Nonna, and with Helena as her new mother, it was clear they were leaving the dark wood behind and heading into the clearing.

Today, Joe and Helena are married and as well as Isabel, seven, they have a four-month-old son, James.

Dante, writes Joe in his memoir, “taught me that you can love somebody without a body in a certain way, but that you must reserve your truest love for somebody whose breath you can hear and feel – your child’s, your wife’s – and that you may visit the Underworld but you cannot live there.”

Joe’s life now is very much as he once expected: he has a wife, a lively and fun-filled family home in Tivoli on the Hudson river, and he is fully involved in his children’s lives. But he is grateful for every day and every hour that they have together, for once you have experienced how fragile life can be, you never forget that it can all disappear in an instant.

Like Dante, Joe has created from his dark wood a work he probably never would have otherwise. Over the last few years he had been working on two books, one that sought to introduce a general readership to his beloved Dante, the other a memoir in which he sought to pay tribute to Katherine. At some point, it dawned on him that these two books were one and the same and he wove their narratives together. “Someone once said to me, you should only write a necessary book. And this feels like a necessary book because I want to share with other people who might be going through a similar grief that, however dark the wood is, they will come through.”

In a Dark Wood: What Dante Taught Me About Grief, Healing and the Mysteries of Love by Joseph Luzzi is published by William Collins, £16.99. To order a copy for £13.59, go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.