In October 2015, Connie Walker received an email with the subject line “Alberta Williams.” Walker, then an investigative journalist at the CBC, had never heard of Williams, a Gitxsan woman who was murdered in 1989, at twenty-four, and whose killer had never been caught. The message contained a single line: the name of Williams’s alleged murderer.

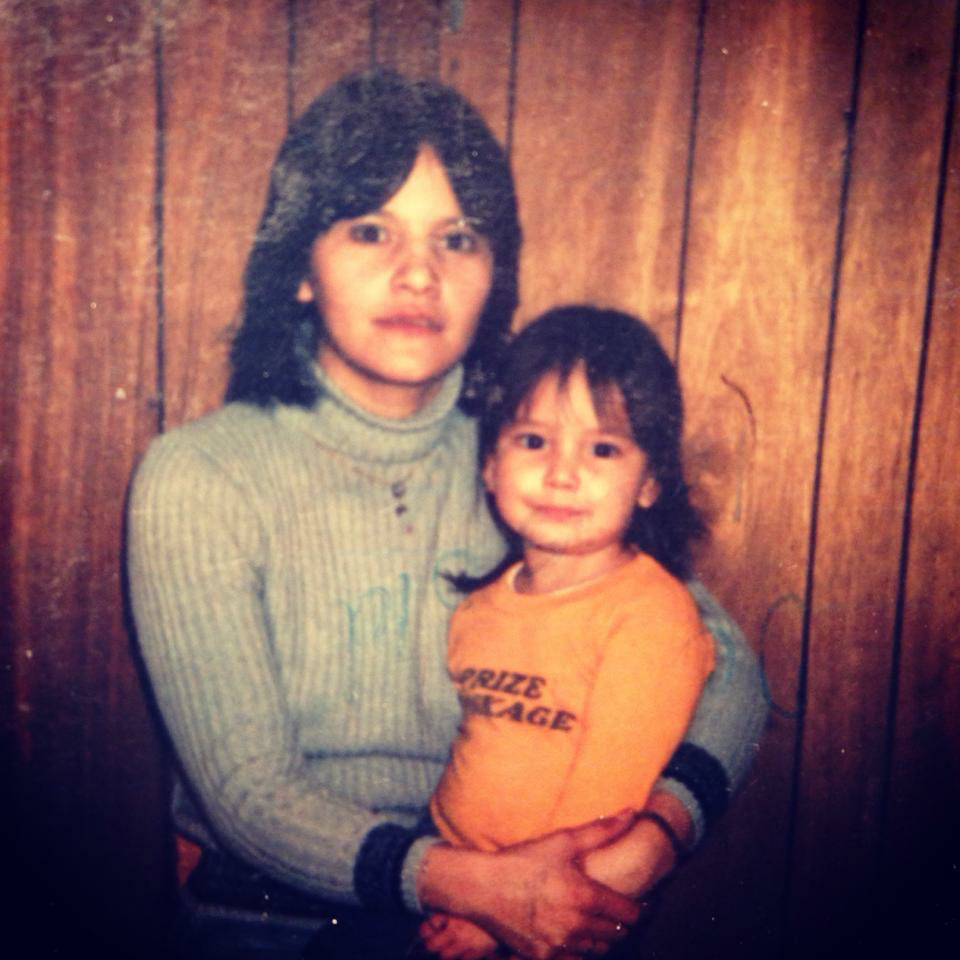

By then, Walker had been trying to tell stories about missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls for years. Walker recalls reading a news story in 1996, when she was sixteen, about the murder of a Saulteaux woman named Pamela George, who was sexually assaulted and then brutally beaten by two young white men. Walker was struck by how George, a mother of two children, had been characterized by the media only as a sex worker. She wondered why there were no Indigenous journalists covering the murder. So she became one, writing about George in her first story for her high school newsletter.

At the CBC, where she began working as an associate producer in 2005, then as a reporter three years later, Walker fought to cover stories about Indigenous women who had gone missing or been killed, leaving behind anguished families and endless questions, their stories often ignored or quickly forgotten. Many of them, like Williams, died or disappeared along the Highway of Tears in northern British Columbia, but nowhere in Canada was safe. When the tip about Williams’s alleged killer appeared, Walker had recently helped compile a database for the CBC of more than 230 unsolved cases across the country, representing a fraction of the nearly 1,200 Indigenous women and girls the RCMP estimated had gone missing or been murdered between 1980 and 2012. Advocates believe the true figure is much higher, particularly since there is no comprehensive national database for missing persons. In Saskatchewan, where Walker grew up, Indigenous people make up 17 percent of the province’s population, but Indigenous women have accounted for approximately half of all female missing persons cases since 1948.

Convincing editors and producers that these stories mattered, however, wasn’t always easy. Early in her career at the network, while pitching a story about a missing Dakota woman named Amber Redman, Walker was cut off mid-pitch by a producer who asked if she was talking about another “poor Indian” story. Her pitch had questioned why Redman had received so little attention compared to the national headlines about Alicia Ross, a young blonde woman from Markham, Ontario, who had also recently disappeared. The dismissive response she received was its own answer. Ultimately, Walker didn’t get to tell that story; it would be almost three years before Redman’s body was found.

After she received the tip about Williams, Walker decided to try a different approach to reporting the story, one that would connect her death to the larger epidemic of violence against Indigenous women. When Missing & Murdered: Who Killed Alberta Williams?, a multi-episode narrative podcast Walker hosted and co-produced, aired in 2016, it was a breakout hit. In the show’s second season, Finding Cleo, Walker helped a family fractured by the Sixties Scoop learn what had really happened to their sister, who died a few years after being apprehended by child welfare and adopted by a white couple. In December 2019, when audiences were expecting news of a third season, Walker announced that she had left the national broadcaster and joined Gimlet Media, a growing American podcast company. Two years later, Gimlet released the first season of Stolen, which appeared like a natural continuation of Missing & Murdered, following Walker as she investigated the 2018 disappearance of a young woman named Jermain Charlo in Missoula, Montana.

In Stolen’s second season, Walker shifted focus to her own family as she searched for the priest who had abused her late father when he was a boy at St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Duck Lake, Saskatchewan. The show has attracted millions of listeners, and last year, the second season won a Pulitzer Prize and a Peabody Award. Walker had booked a speaking engagement in Seattle on the day the Pulitzers were announced, and she was excitedly sharing the news with her producer. “The cab driver was like, ‘Sounds like you got some good news.’ And I said, yeah, we just found out we won a Pulitzer Prize. He was like, ‘What is that?’” she recalls. “That was good, it brought me down to earth.”

True crime podcasts typically aim to solve a mystery by finding an ending, by uncovering new evidence or pointing a finger at the likely killer, like a campfire story meant to thrill and frighten. Indigenous stories, too, are often reduced to their tragic endings: a brutal death, a haunting absence. But Walker goes in the other direction, by showing who a person was before they became a statistic, emphasizing the complexity and humanity of her subjects while avoiding the genre’s tendency to sensationalize the most lurid details of their deaths. And she reaches back even farther, to show how their life and death were shaped by the complex legacy of colonialism that ripples across generations. In doing so, she accomplishes something even more profound: by using journalistic tropes to reveal how little North Americans understand about the lives—and deaths—of Indigenous people, she is transforming how we understand both the present and the past.

Having won the two biggest awards in North American journalism and cultivated a massive audience, Walker appeared to have unstoppable career momentum as she prepared for the release of Stolen’s third season. But her story took an unexpected twist: in December 2023, Spotify, which had bought Gimlet in 2019, confirmed that the show had been axed (season three will still air). Walker, whose success represented a beacon of hope for despairing journalists, was now a symbol of the profession’s alarming, inescapable collapse. And it illuminated another mystery too, this one about the industry itself: If executives don’t see the value in a show as popular and critically acclaimed as Stolen or Missing & Murdered, what will it take to convince them that these stories are worth telling?

Walker spent most of her childhood in File Hills, a tribal community of four First Nations about an hour’s drive northeast of Regina. Her parents split up when she was young; her father was volatile and physically abusive to her mother while they were together. After her parents separated, she moved with her mom to Okanese First Nation, where Walker’s close-knit family included her siblings, her maternal grandparents, and many cousins, aunties, and uncles. “Nicknames are big in my family,” says Walker, whose family calls her Totter; like with many nicknames, its origins are uncertain, but she’s pretty sure it was coined by a cousin who couldn’t pronounce “Connie” when he was little. “I have relatives where it wasn’t until I got older that I realized, wait, that’s not their name.”

Walker was especially close with her grandfather, and as a teenager, she often spent her Saturdays chauffeuring him on long drives to garage sales. While at the Saskatchewan Indian Federated College (now First Nations University of Canada), she took a class that required recording an oral history. “So I set up my video camera and interviewed my grandpa that weekend,” she says. “That was the first time I learned that he went to Lebret (Qu’Appelle) Residential School when he was six years old.” All four of her grandparents attended residential school, as did her father, but none of them had ever spoken to her about their experiences before. Walker, who thought she knew her grandfather so well, was stunned. “We’d spent hours together, talking about farming, talking about sports . . . and here was this giant thing.” As in the podcasts she would later create, it was a revelation from the past that transformed a once familiar story, a mystery pointing to a larger, more complicated tale.

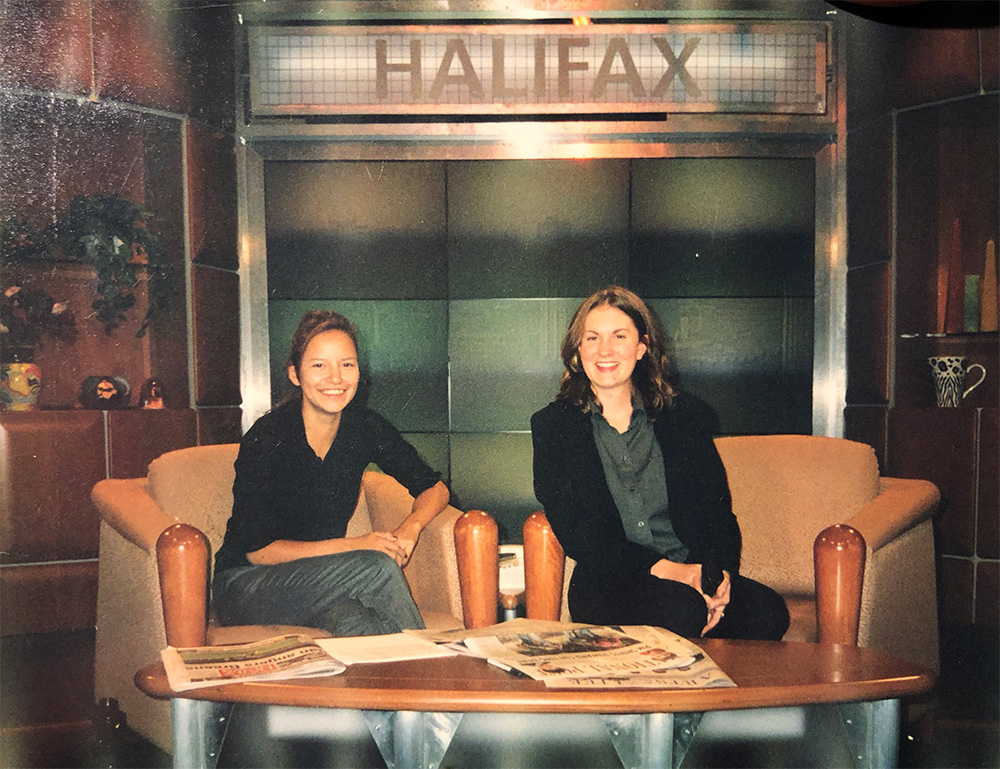

Walker never finished her degree. In her third year at SIFC, she received a scholarship to intern with CBC Halifax as a chase producer, booking guests for news segments. Once, after booking a Mi’kmaq chief to discuss a fisheries dispute for a Monday segment, her producer warned her that Indians were liable to get drunk all weekend and forget to show up. “I just remember the feeling of embarrassment and anger,” she said in a 2023 interview for the Warrior Life Podcast, recalling how she scanned the room to see if anyone else had overheard, thinking, It’ll be my word against hers. While taking a smoke break in the parking lot one day, she met a producer for Street Cents, a CBC culture show for youth. They were looking for a new host. The producer asked her if she would like to audition. Walker did, and she got the job, leapfrogging from uncertain intern to TV host. She spent four years with Street Cents before moving into news, based out of Toronto. In 2012, she co-produced 8th Fire, a wide-ranging four-part documentary about reconciliation, hosted by Wab Kinew, then a reporter. The series featured interviews with a diverse array of Indigenous people who challenged stereotypes and common misconceptions; viewers learned that the majority of Indigenous people do, in fact, pay taxes—and that residential schools were not distant history but had operated in Canada until 1996. The next year, Walker helped create CBC Aboriginal (now called CBC Indigenous) and stepped into a new role as one of only two full-time journalists at the online platform.

Anishinaabe journalist Duncan McCue joined the CBC a couple years before Walker, but the two didn’t cross paths for more than a decade. “The thing about CBC, when Connie and I both joined, is that the Indigenous staff didn’t really know each other that well,” he says. There was only a handful of them, spread out across newsrooms, with little opportunity to collaborate or discover how similar their experiences and concerns as Indigenous reporters were. But after CBC Aboriginal launched, Walker began contributing stories, along with other Indigenous reporters, including Jillian Taylor, whose sustained, sensitive reporting on the death of fifteen-year-old Tina Fontaine helped the public see her as not just another victim but a child who was deeply loved and missed. But that reporting didn’t come easy. “The people who held the purse strings were not always keen to spend the precious resources of our newsrooms on sending people out into isolated communities,” says McCue.

CBC Indigenous quickly built an audience, demonstrating through growing readership that these issues mattered not just to Indigenous communities but to non-Indigenous readers as well—something the team could prove thanks to the recent innovation of digital analytics. “I think that the initial year of CBC Indigenous was a real eye-opener for the digital team, and for CBC News in general,” says McCue. “Because they recognized—and we had the analytics to support it—that there was an appetite for stories that went outside the conventional kind of judgment as to what was newsworthy.” Within a year, Walker says, CBC Indigenous was outcompeting some provinces or regions of CBC coverage in page views and social media engagement, which surprised everyone. “When you’re trying to climb the ladder in the newsroom, there’s a fear that you’ll be pigeonholed if you decide to focus on Indigenous stories,” says McCue. “But Connie said: this is bigger than me and my career, this is something we need as a network . . . whereas before, the CBC had never really looked at it that way.”

The success of CBC Indigenous made an irrefutable case for the value of Indigenous stories. Still, Walker struggled with the expectations of news reporting and the limitations of the news story, which focused on the immediate and left little space for reflection or context. In 2015, while reporting on the murder of a fifteen-year-old Cree girl named Leah Anderson, she was frustrated by how the story had to be stripped of nuance and complexity to fit a thirteen-minute TV news segment. “They were in the child welfare system, she and her siblings. There was a really dire housing situation,” she recalls. “There was just so much going on and I felt like we were having to put blinders on and focus on one single thing.” Audiences were finally seeing more stories about missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, but they weren’t seeing how those stories were all connected.

A few months later, when she received the email about Alberta Williams’s alleged killer, the story was initially envisioned as a two-minute news segment. Instead, Walker began to think about a different way of telling it, and stories like it—a way that wouldn’t just focus on a final sensational chapter.

At first glance, Williams’s story sounded like one audiences had heard before, one they thought they knew: another Indigenous woman whose life was ended brutally along the Highway of Tears. But once Walker started investigating, she realized there was a chance to portray one woman beyond the circumstances of her death and explain how and why the murders of Indigenous women so often go unsolved, their families fighting for answers to so many unanswered questions. But to tell that deeper story, she would need more than a brief news segment.

Like almost everyone else, Walker can trace her obsession with investigative, narrative-driven podcasts to Serial, the 2014 investigation into the 1999 murder of Baltimore high school student Hae Min Lee and the conviction of her former boyfriend Adnan Syed. Walker can still recall exactly how she and her husband devoured the blockbuster series. “We sat in our living room, on opposite sides—I was on a loveseat, and he was on the couch—and we listened together in silence.” It was a revelation—a strikingly different way to tell stories, one that brought readers into the heart and process of an investigation and drew them along as the reporters chased leads and weighed evidence.

Walker had never done a podcast before, but she and her producer Marnie Luke successfully pitched the CBC on turning Williams’s murder investigation into a true crime podcast that would go beyond the murder to reveal the intergenerational traumas and inequities that make Indigenous people so vulnerable to violence. Walker says the fourth episode of the season, which shifted focus to residential schools, was a revelation for many listeners. “I remember hearing from health care workers and people who were working with Indigenous communities every day, feeling like they didn’t know or understand [the impact of residential schools] before listening to the podcast,” she recalls. Deviating from the central mystery of Williams’s murder had not turned audiences off; instead, they were receptive, eager for a bigger picture. It was a “eureka moment” for Walker.

Even though Missing & Murdered reached millions of listeners and was nominated for a Webby Award, while working on its second season, a manager told her, “There won’t be another podcast in your future. This is it. This is the end.” Walker hoped management would change their minds if Finding Cleo proved to be an even bigger success than the first. It was, but the CBC didn’t budge. “Every other media organization is struggling to do many, many things with fewer and fewer resources, and they have to make really difficult decisions,” she says. What makes investigative podcasts so engaging—their depth, their length, the time it takes to report them—also makes them costly to produce, and Walker says she was told her podcasts were too expensive and time consuming.

According to McCue, who calls Finding Cleo and Who Killed Alberta Williams? “two of the most successful podcasts that CBC has ever had,” the financial question is only part of the answer as to why the CBC lost interest in Walker’s projects. “I think the loss of Connie speaks as much to the inequities that female journalists face in this business as anything else.”

Instead of another podcast, Walker was offered a contract as a reporter with The Fifth Estate, the CBC’s flagship investigative documentary TV program. After reviewing the contract, she says, she asked if the salary was comparable to that of the other hosts and learned that she would be paid less. She couldn’t do it. So she left Canadian media altogether. “As excited as I was to join Gimlet and to be able to focus exclusively on podcasting, I think, honestly, I was really sad for a long time,” she says. “I feel like my work is an extension of who I am, and I always felt like I was doing it for a bigger purpose than my job or my career—it was to try to help my family and my community and other Indigenous people in Canada.”

In the early summer of 2021, shortly after the finale of Stolen’s first season, The Search for Jermain, was released, news broke that ground-penetrating radar had discovered suspected unmarked graves on the grounds of a residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia. The horrifying news shook something loose in Indigenous communities across Canada. Survivors began sharing their stories of residential school. “I remember seeing family members who had never ever even said the words aloud, at least in my presence,” says Walker. “Now we’re making Facebook posts about it.”

One post was written by her brother Hal, and it was about their father, Howard Cameron, who died in 2013. Hal had written that when Cameron was a young RCMP officer, he had pulled over a suspected drunk driver one night and found himself looking into the eyes of the priest who had abused him at St. Michael’s Indian Residential School. According to Walker’s brother, their father pulled the man from his car and beat him on the side of the road, then drove away.

That summer, she returned to Saskatchewan for a visit. She recorded interviews with other family members who had attended St. Michael’s and tried to figure out if their recollections added up to something bigger. “I just felt like that was the way to deal with the grief that I felt when I learned about his experience of abuse,” she says. “I was unsettled by it for so long, and I just felt like I knew I wanted to do it personally. But whether it was going to be a story or not, I couldn’t see.” Then one of her producers, Anya Schultz, asked a question that brought the project into focus: “Why don’t we try to find the priest?”

“Lots of people are not going to want to listen to an eight-episode podcast on residential schools,” says Walker. “But if it’s framed with this compelling question, then you’ll attract more people who don’t even think they care about the Indigenous issues.” The response to the residential school episode of Who Killed Alberta Williams? had proved that a single story, a single question, could provide an entry point for audiences to learn about that larger context, one that could change the way they understood the historic and contemporary forces that shape Indigenous life.

The structure of the investigation also served an important purpose for Walker. She had seen how her father changed toward the end of his life; he gave up drinking and tried to make amends. But he died before she ever really had a chance to get to know him, and in the interviews she conducted with her family members for Surviving St. Michael’s, she finally began to understand him. “At a certain point, I realized I need the investigation too,” she recalls. “This search for accountability—it’s a way to channel my grief into anger. It’s the thing that propels me forward.”

St. Michael’s was just one of more than 130 residential schools that operated across Canada during the twentieth century. It was opened in 1894 and was one of the last to close in 1996—though for its final fourteen years, it was run by the Saskatoon District Chiefs. When Walker began expanding the investigation beyond her family, she called Betty Ann Adam, a Dene journalist of almost thirty years at the Saskatoon StarPhoenix, and asked her to join the production team and conduct interviews with survivors. Adam later phoned those survivors when the season started winning major awards. One expressed her amazement that people were finally learning what had happened to them as children. “To be able to tell the survivors that people are hearing their stories, that they’re moved by the stories and that they care . . . it gives the survivors some sense of the dignity that comes with being heard and believed,” says Adam. “It wasn’t just about the product, the audio product that was created. It was really about this historical reckoning and everyone stopping momentarily to look at this and go—this really happened.”

“We’re all talking about reconciliation and what it means to reconcile,” Walker says, “but we don’t even understand the truth yet.”

For Walker, working with Adam as well as Métis producer Chantelle Bellrichard on Stolen was the first time she was part of an experienced Indigenous team. That experience is still rare for Indigenous journalists. McCue, citing a 2022 diversity survey from the Canadian Association of Journalists, points out that about eight in ten newsrooms still have no Indigenous or Black staff at all. “That needs to change,” says McCue, who joined Carleton University as a professor of Indigenous journalism last year after twenty-five years at the CBC. “But what concerns me more is the efforts that we make—that the CBC makes—to ensure that Indigenous staff feel like they have a culturally safe workplace. And that needs to be more than lip service.”

When Stolen began investigating the history of St. Michael’s, there was more attention being paid to residential schools than ever before, but there was also more denial of their impact. More unmarked graves had been detected at former school sites across Canada, but some people had denounced them as a “hoax.” Even former prime minister Jean Chrétien claimed he had never heard reports of abuse when he was minister of Indian affairs, before comparing his own boarding school experience to that of residential school survivors.

One reason Canadians are still largely ignorant of the horrors of residential schools, as Walker’s investigation uncovers, is that the majority of survivor testimonies are locked away. More than 38,000 claims were reviewed by the Independent Assessment Process, established as part of the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement in 2006, which required survivors to recount the horrific details of their abuse in order to be eligible for compensation from the Government of Canada. Although survivors were describing crimes, the process was not a criminal one, and no abusers were charged as a result. The resulting testimonies were sealed, protecting the privacy of victims—but also their abusers.

Because they couldn’t access those records, the Stolen team reviewed lawsuits filed by the survivors of St. Michael’s before the IAP process was established. They found more than 200 allegations of sexual abuse against forty-five staff members of St. Michael’s, spanning around eighty years. What followed was a partial reconstruction of a single institution, its brutal and bloody history laid bare. And even as Walker looks ahead to the next season of Stolen, part of her is still thinking about all the stories in those lawsuits, each one important to a family just like hers, each devastating in its own way.

Despite how far Walker had come, despite the millions of listeners and the awards, the comments lingered. “How many more of these stories can you do? They’re kind of the same story,” she recalls someone asking her. It’s the way the stories have often been told that creates this impression, because so many end the same way: an abused child becomes a traumatized adult; a woman disappears without a trace; a murder case grows cold from neglect. Another poor Indian. But by tracing those stories back to their beginnings, Walker reveals that they’re never simple and never the same. “Every family has a story,” she says. “Every single family, every single woman, girl, man, or boy is an opportunity to understand a bigger story about Indigenous people, about Canadian history, about colonization.”

Beginning in 2013 with Orange Shirt Day and then in 2021 with the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, each year on September 30, Canada recognizes the legacy of residential schools, a legacy that is still largely buried by the same federal government that now honours residential school survivors. The public may never fully know what survivors endured at those schools—unless, of course, those stories are told. In recent years, Walker says, Canadians have vaulted toward reconciliation while skipping a crucial step. “We’re all talking about reconciliation and what it means to reconcile,” she says, “but we don’t even understand the truth yet.”

The third season of Stolen, being released early this year, unfolds in the Navajo Nation, a place Walker didn’t know much about, and she admits it’s a challenge to report in communities where she’s an outsider. “Just because I’m Indigenous and Cree from Canada, that doesn’t necessarily give me any connection to the Navajo people,” she says. At more than 27,000 square miles, the Navajo Nation is the largest reservation in the United States; Canada’s largest reserve, belonging to the Blood Tribe First Nation, is just under 546 square miles. Navajo is also the largest nation by enrolment, with nearly 400,000 members. For the podcast, Walker and her team embedded with the Navajo police force to understand the investigations into the disappearance of two women, which allowed them to tell a bigger story about the crisis of policing in Indigenous communities. She likens her approach to that of The Wire, the 2000s TV show set in Baltimore, and how each season focused on a different system in the city, like education or policing. It’s a model she was inspired by for her podcast work, structuring each season around a larger issue that affects Indigenous communities.

Her perspective on telling stories has evolved since she started out as a journalist as her understanding of trauma has evolved—including her own. Walker recalls how conflicted she felt earlier in her career asking family members of people who had disappeared or died to relive their worst memories. The prevailing thinking back then was that any harm caused by an interview was justified by the greater good of raising awareness about an unsolved murder, but reporters weren’t trained to mitigate the emotional impact on subjects. Things have changed since then, and Walker’s personal experience as both storyteller and subject has deepened her understanding of how to interrogate a painful history. “Doing Surviving St. Michael’s felt like an exercise in trauma-informed journalism as a form of healing,” she says. “If you are given agency, and you are respected in the telling of your story, that can be an empowering part of your healing process.” In the final episode of Surviving St. Michael’s, Walker shares that one of her uncles, who was also sexually abused at residential school, went on to perpetuate the cycle of abuse in his own family. And finally, Walker opens up about her own experience of sexual abuse. It’s a stunning moment, a feat of bravery but also of storytelling, one that profoundly alters the listener’s understanding of the story they thought they were hearing. Truth, it shows, can be a path to healing. Each of Walker’s podcasts has shown how a single tragedy—a missing mother, a lost sister—connects back to the violence of colonization, which touched and continues to touch every Indigenous family. And each one defies expectations, proving that a tragic and familiar ending is never the whole story.

That’s part of the reason she was drawn to podcasts a decade ago: drawing back the curtain of an investigation, revealing not just the triumphant discoveries but the hesitations, the existential questions, the terrifying uncertainties. When Walker began her career, there were few Indigenous stories being reported and fewer Indigenous journalists to cover them. There’s still a long way to go to tell them all and tell them right. “I do feel this urgency. For so long in my career, I was like, ‘I’d like to do that, but it’s not really possible. There’s no interest, or that’s not my job, or whatever,’” she says. She’s a long way from the intern who was told that Indigenous sources were unreliable drunks, and the young reporter whose pitch was once dismissed as another “poor Indian” tale, but she’ll never forget them. “Now that I’m able to, I just have to keep going for as long as I can. Keep trying to tell as many stories as I can. Because as we’ve seen, there are no guarantees.”

Shortly before Walker joined Gimlet Media in 2019, the company was acquired by Spotify. In June last year, a few weeks after the Surviving St. Michael’s team won the Pulitzer and Peabody awards, Gimlet was dissolved into a new unit called Spotify Studios. At one point, Gimlet represented the pinnacle of the podcast boom, and its dissolution is viewed by some as the end of a golden era. Between 2020 and 2022, one analysis found that the number of new podcasts every year had declined by 80 percent while many existing ones were cancelled. In April 2018, Gimlet launched a podcast called The Habitat, about a simulated mission to Mars, which co-founder Alex Blumberg later described as both the network’s “biggest launch ever” and a financial flop.

As Walker learned with Missing & Murdered, even successful shows are subject to the secretive economic calculus that guides the decisions of media outlets, and a huge audience does not necessarily correlate with a company’s perception of profitability. It’s hard to quantify the value of a podcast that reaches millions of listeners and changes the way they understand the legacy of residential schools; it’s easier to tally the savings of not doing it. In early December, Spotify announced it was eliminating 1,500 jobs, or 17 percent of its workforce. (An additional 800 employees were let go in two previous rounds of layoffs last year.) The same day, the CBC announced it was eliminating 800 jobs, or 10 percent of its workforce, in response to a projected $125 million shortfall. Hours later, it was confirmed that two of Spotify’s acclaimed podcasts had been cancelled, Heavyweight and Stolen.

Even in a year of relentless media layoffs, it was still shocking that Walker was facing the same fate as thousands of other journalists: scrambling for a foothold in a crumbling industry. But Stolen’s improbable cancellation laid bare the contradictions of an industry whose decisions are guided not by audiences or accolades but by a small coterie of executives and investors who have very different definitions of value. Spotify, which saw its stock value rise 7 percent immediately after the layoff announcement, reported that third-quarter revenues had grown by 11 percent. In a memo announcing the layoffs, Spotify CEO Daniel Ek wrote, “By most metrics, we were more productive but less efficient. We need to be both.” According to Bloomberg, the platform was focusing its efforts on “licensed shows that run year-round,” like The Joe Rogan Experience. That strategy leaves no room for investigative journalism, which can never be churned out at the pace of a talk show and which by definition requires depth and consideration.

For her part, Walker is prepared to adapt. Her career has been a series of successes that confounded long-held industry beliefs about the lack of interest in Indigenous stories, with her pushing past those beliefs in order to connect directly with audiences. In late October, she was sanguine and open to possibility. “I don’t have a plan,” she says. “I think that my plan is: I want to keep doing this work in one shape or another.” She loves the podcast format but says she’d also like to write a book someday and work in film and television.

Stolen may be coming to an end on Spotify, but as Walker’s podcasts have demonstrated time and again, a story is always so much more than its ending. Look back and you’ll find it’s just one piece of a bigger picture. Stolen has impacted millions of listeners and showed them how much they have left to learn about the lives and histories of Indigenous people. “There’s so many different expressions that our stories can take, and as long as I’m getting to do this work in some way, I feel like that’s the most important thing,” she says. “We’re not going back to when people believed that our stories weren’t important.”

Correction, February 1, 2024: An earlier version of this article stated that File Hill is a tribal community of eleven First Nations. In fact, it is made up of four. The Walrus regrets the error.