Review: Gillian Wearing Editing Life, and Cindy Sherman Untitled Film Still #58, PHOTO 2022.

As we struggle to recover from the pandemic, “Being Human” – the theme of this year’s PHOTO 2022 international biennale in Melbourne – could not be more apt.

It is a recognition that interacting with other humans is the most cherished part of being alive, and one which we enthusiastically embrace.

This biennale has a wealth of outdoor experiences as well as indoor ones. Walks around Melbourne create surprise encounters in the city (or curated walks and cycle tours are available).

There are five stands: society, nature, history, mortality and self. The latter two are keenly addressed in works by Gillian Wearing at ACMI and Cindy Sherman outside the NGV Australia.

Through their close proximity, the PHOTO 2022 curators have effectively encouraged a conversation between artists.

Both adopt impressive scale. Sherman’s work is larger than most billboards at 20 metres high. Wearing’s giant floor-to-ceiling self-portraits wrap around the gallery.

Both artists use their own bodies and faces to communicate ideas beyond the self; they connect to human experience of the world, mortality and gender.

The masks of Gillian Wearing

British conceptual artist Gillian Wearing is on display at ACMI in a survey of four works.

In Rock ‘n’ Roll 70 Wallpaper, she asked collaborators to visualise how she might look when she is 70, creating 15 different imaginary photographic portraits.

Using age rendering tools created by artificial intelligence, her possible future selves are depicted.

The images’ size, as a collage of portraits extending floor to ceiling, create a dramatic experience while also illuminating the psychological dimension of the portraits.

On walking into the gallery, you are surrounded by the many kinds of expressions and gazes of a variously aged Wearing: vulnerable, defensive, benign.

The work asks us to question how we feel about and react to ageing. How we might respond to not knowing whether an image is a truthful depiction. And, emotionally, how we contemplate the unknown factor of what time will impose upon the human form.

A second work is a deep fake video made with collaborators Wieden+Kennedy, a global advertising agency best known for working with Nike.

In the video, a digital mask of Wearing’s face is disconcertingly mapped onto the faces of others, making them eerily familiar and yet unknown. The participants were strangers responding to an advertisement to be in the film. On watching this, I am struck by the question: what is the true self? Are you obedient to social norms, a fraud, an authentic or frustrated character?

A person is more than a name, or an image. We embody and reflect experiences. Can we be who we say we are, or the persona we offer to the world?

The work creates the impression we are all one, an idea undercut by knowing that these are all constructed portraits.

There are two self-portraits, one of Wearing at age 17, and another titled Self-Portrait of Me Now in A Mask. Together, they expand Wearing’s reflection on ageing. The latter explicitly picks up on Wearing’s extensive interest in masking, self-production and personas.

As the video work in the exhibition offers:

We all wear masks. We’re all actors. When you leave your front door in the morning, you’re putting on a performance for the world.

Cindy Sherman and women photographers

Sherman’s work conveys a similar sentiment.

All representation – even of real things – is selected and presented by someone. When we are photographed, we offer an idea of ourselves to the photographer, we perform ourselves. The photographer selects the frame, the tone, the style and which image is presented.

From this point of view, an image is never neutral.

The American artist Cindy Sherman has portrayed herself in her photographs as film stars, unhappy housewives, socialites and other iconic female roles — conveying commentary on gender and celebrity.

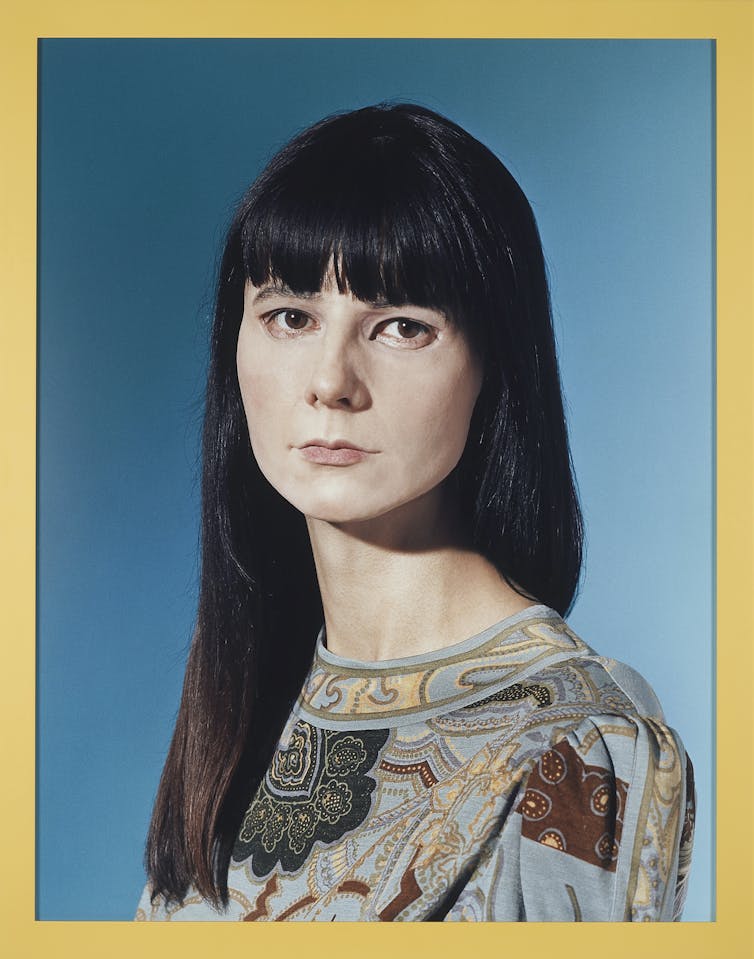

The image outside the NGV Australia on Flinders Street, Untitled Film Still #58, is one from a series of 69 self-portraits Sherman produced from 1977-80. All in black and white, they recall scenes from movies. In most of those images, a single female figure appears as if caught spontaneously.

The monumental presence in Flinders Street is spectacular. The woman looks at something beyond the frame – as many in this series do – and the averted gaze invites the viewer to contemplate both the woman and what is just out of frame.

Read more: Here's looking at: Cindy Sherman 'Head Shots'

Perhaps she is aware of being looked at or objectified, concerned with being on the street and wary of the urban environment.

Wearing edits life while Sherman imitates it, but in all of these works, the images are not about the photographers themselves as people. They draw on their experience, but are about issues such as what women face in their lives, bodies and culture, and about how visual representations construct meaning.

Gillian Wearing: Editing Life and Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still #58 are on display until 22 May.

Lisa French does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.