When Charles Cullen’s arrest first made the news, the former nurse was reported to have been sharing a meal of spring rolls and beer with a female friend – “a date”, The New York Times described her – when officers apprehended him. The woman was in fact no date, but rather Amy Loughren, a former coworker of Cullen who had been working with investigators – and ultimately helped authorities arrest and prosecute a serial killer nurse.

Cullen worked for 16 years at hospitals in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Following his arrest in December 2003, he confessed to killing 29 patients, often by administering drug overdoses, at several of the healthcare facilities that employed him. The case marked one of the most infamous instances of serial killings in New Jersey. It also prompted questions about the system that enabled Cullen to keep practicing, even as people repeatedly died in unexpected circumstances under his care.

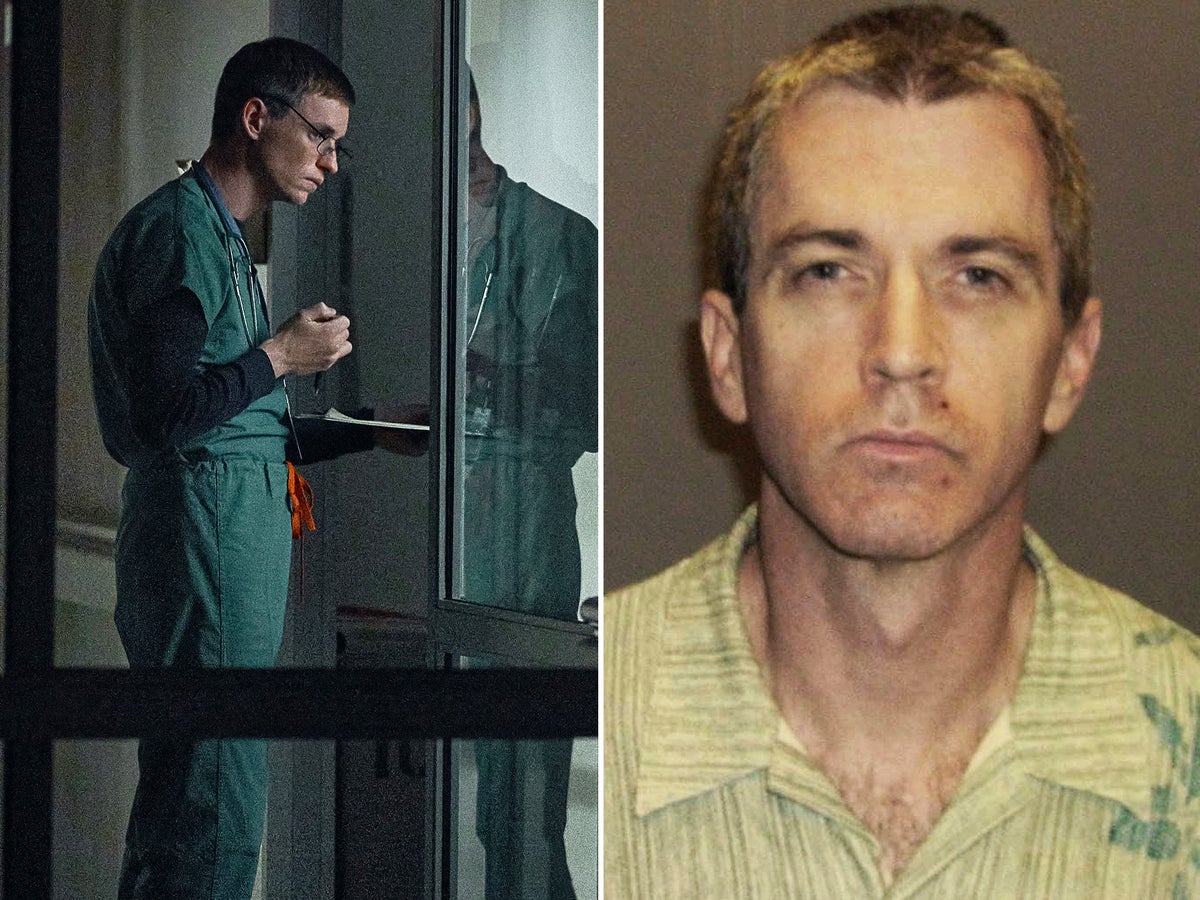

A dramatised version of Cullen’s crimes is the subject of the Netflix film The Good Nurse. Eddie Redmayne stars as Cullen and Jessica Chastain as Loughren. It’s the first English-language movie by Danish screenwriter Tobias Lindholm (whose previous credits include the 2020 Another Round starring Mads Mikkelsen, and the 2015 Oscar-nominated A War).

The film is adapted from the 2013 book The Good Nurse: A True Story of Medicine, Madness, and Murder by journalist Charles Graeber. (In an enthusiastic review of the book, Stephen King referenced the murderous nurse at the centre of his own novel Misery, writing: “You think Annie Wilkes was bad? Check out this chilling nonfiction account of Charlie Cullen.” Borrowing from Annie Wilkes’s characteristic parlance, King added of Cullen: “Now, there’s a real cockadoodie brat.”)

Born on 22 February 1960 in West Orange, New Jersey, Cullen had what he described to Graeber as a “miserable” childhood. His family was working-class and Irish Catholic; his father died not long after his birth and his mother died while Cullen was in high school. Cullen enlisted in the US Navy, where he occasionally exhibited troubling behaviour and was known to keep to himself. After a suicide attempt (one of several, according to The New York Times), Cullen was medically discharged in March of 1984.

Cullen enrolled in nursing school in Montclair, New Jersey, that same year. To fund his studies, he worked at a series of restaurant franchises; at Roy Rogers, he met Adrianne Baum, whom he married in 1987, the year of his graduation. As a nursing student, Cullen was voted class president – a “symbolic position”, Graeber writes in his book, but still a special one, which made Cullen his school’s “chosen son.”

Over the course of his career, Cullen changed jobs frequently, shuffling through nine positions in a period of 11 years, The New York Times reported in 2004. His first full-time job as a nurse was at St Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, New Jersey, where, according to one former coworker, he was known to be staunchly private. “You’d ask, ‘Are you married?’ or anything like that, and you’d get one-word answers,’” Jeanne T Hackett told The New York Times for its 2004 piece about Cullen. “’I remember the day I laid eyes on his car, and I said, ‘Oh my God, now I know something about Charlie Cullen: I know what his car looks like.’”

Later on, Cullen’s places of employment included Warren Hospital in Phillipsburg, New Jersey; Morristown Memorial in Morristown, New Jersey; and Liberty Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Allentown, Pennsylvania. “He worked in the cardiac and intensive care units, where death is often expected, surrounded by the most gravely ill patients, many of them unconscious,” The New York Times wrote. “... Several medical serial killers have found working nights, with the sickest of patients, to their liking.”

Cullen’s first murder victim is believed to have been John W Yengo Sr, a judge in Jersey City who died in 1988 aged 72. An obituary published at the time of his death states that he died of “Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a rare allergic reaction.” But after Cullen’s arrest, it turned out – as reported by The Associated Press in 2004 – that while Yengo had been admitted to St Barnabas Hospital due to an allergic reaction, Cullen killed him by injecting him with a drug that stopped his heart.

‘”I was always suspicious because it happened so quickly,” Yengo’s daughter told the news agency at the time. “’Without knowing anything different, I assumed it was God’’s will. Clearly it wasn’t.”

In 1993, Helen Dean, 91, a patient at Warren Hospital, was recovering from breast cancer surgery when Cullen entered her room, asked her son Larry to leave, and gave her an injection. The next day, she became “violently ill”, Graeber writes in his book, and died of heart failure.

A post-mortem examination conducted in 1993 did not test for digoxin, a substance that later turned out to be frequently used by Cullen in his killings. Helen Dean’s death was deemed to have been the result of natural causes, but Larry Dean was convinced Cullen had killed his mother. He died in 2001, before the nurse was arrested and his crimes revealed. In 2004, Helen Dean’s body was exhumed for further testing. Cullen eventually admitted to killing her.

Five years later, 78-year-old Ottomar Schramm, who suffered from strokes, was admitted to Easton Hospital after aspirating food into his lungs. His daughter Kristina Toth, according to Graeber, later remembered her father being taken away for “tests” by a “strange man” with a syringe. Schramm’s health deteriorated unexpectedly before improving. Blood tests revealed abnormally high levels of digoxin, even though he hadn’t been prescribed the substance. Schramm’s health took another turn, and he died a few days later, in December 1998. His death was initially deemed accidental. Cullen ended up pleading guilty to Schramm’s murder in 2004.

In 2003, the Reverend Florian Gall was taken to the Somerset Medical Center in New Jersey with pneumonia and sepsis. Though he was seriously ill and placed on a ventilator, his loved ones hoped he would recover, as he had done during previous bouts of sickness, The New York Times reported. One morning in June, Gall went into cardiac arrest and could not be resuscitated. His body was exhumed after Cullen’s arrest, and Cullen eventually pleaded guilty to killing the priest by injecting him with digoxin.

Even when Cullen was fired from a job, which happened several times over the course of his career, he was able to find work at new facilities. In its later examination of the case, The New York Times posited this was mainly due to “weak” reporting systems at the state and federal level for healthcare workers, and because “employers frequently [refused] to pass on negative information, even about people they have fired, for fear of being sued for slander by the former employee.”

A letter to the editor published by the newspaper in March 2004 echoed this concern: “The difficulty in identifying professionals who are a risk to patients is rooted in a very widespread problem: those writing references, whether for employment, staff appointment or other positions, believe with some justice that they face expensive and time-consuming litigation if they say anything concerning their unfavorable experience with an individual,” wrote pediatrician David E Knoop, a member of the Credentials Committee at Morristown Memorial Hospital.

In May 2005, in response to the news of Cullen’s crimes, then-New Jersey Governor Richard J Codey signed the Health Care Professional Responsibility and Reporting Enhancement Act, establishing new requirements and protections for people and organisations in the healthcare industry to report healthcare workers who might endanger patients.

While Cullen’s professional life went on seemingly undisturbed for years, his personal life was almost continually tumultuous. Neighbours in media interviews have described him either as a loner who mainly kept to himself, or as a man known to exhibit odd behaviour and mistreat his dog. “In the middle of the night, he’d be out there chasing after the cats, yelling at them and talking to himself,” a neighbour told The New York Times, while another said Cullen would “make weird faces, like he was real angry or thinking really serious” when he thought no one was looking.

Cullen’s marriage to Adrianne Baum ended in divorce. She filed in January 1993, citing “extreme cruelty”, according to The Morning Call, a newspaper covering eastern Pennsylvania. In her filing, she accused him of abusing the two family dogs, and of retaliating when she had complained about his turning off the heat in their homes – by turning it up to uncomfortable levels. In 1993, Baum called the police and made a domestic violence complaint against her husband; according to Graeber, she said Cullen was an alcoholic and that his drinking resulted in dangerous situations.

It was a decade after his divorce, in 2002, that Cullen began working at Somerset Medical Center. There, he met Amy Loughren, the nurse who would ultimately play a pivotal role in his arrest. She was “outspoken and honest”, per Graeber, and “a shadow [Cullen] could shade himself by.” The two formed a work friendship. In 2003, two detectives investigating a string of suspicious hospital patient deaths got in touch with her. Using hospital records, she traced Cullen’s modus operandi and shared her findings with the investigators. But the evidence remained circumstantial, and Cullen himself did not confess to the two detectives. So, in December 2003, the investigators asked Loughren to meet up with Cullen while wearing a wire, hoping she’d get him to talk. Loughren told 60 Minutes in 2013 that when she confronted him about the murders, Cullen told her: “I want to go down fighting.”

Cullen was arrested after his lunch with Loughren, but he still wasn’t talking. Investigators asked for Loughren’s help again. She traveled to the prosecutor’s office to speak with Cullen again. “I wasn’t very honest with him, and there’s a part of me – I still feel guilty about that. I was manipulating him a bit,” Loughren told 60 Minutes of that conversation. “...I told him the investigators were also looking at me, and how could he think that I wasn’t somehow going to be implicated? I remember saying to him, ‘So, who was your first victim? And was it a long time ago? Was it recent?’ And he started to talk.”

Eventually, according to Graeber, Cullen delivered a seven-hour confession. He received 11 life sentences in 2006 and remains imprisoned at the New Jersey State Prison in Trenton. Loughren has left nursing and now works as a hypnotist. Her involvement in the case became known to the public only in 2013, with the publication of Graeber’s book. At that time, Loughren had never told Cullen she was the informant whose work led to his arrest.

The Good Nurse started streaming on 19 October on Netflix in the UK and in the US.