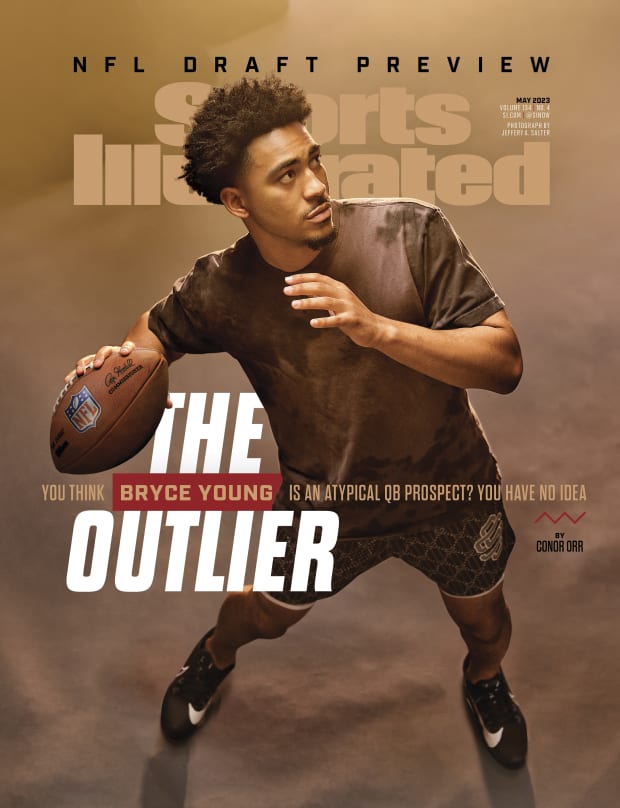

Bryce Young has a body double.

The guy is here on set, sitting in one of those tiny, unstable-looking director’s chairs, wearing the same color hooded sweatshirt as his doppelgänger while Bryce throws a medicine ball in front of a camera. When Body Double Bryce is not here, he is acting in shows like Grown-ish and Snowfall. He has to give the hoodie back to wardrobe on his way out.

His presence is one of the many little benchmarks that remind the Young family that life is changing. Those changes are both unsurprising, given that Bryce has been one of the best quarterbacks in the country since he was in high school, and stunning, in that he is almost completely atypical for an elite NFL prospect at the position. The set is located at a community college in Huntington Beach, a few miles from the Young family home. Young started training here when he was little—he would throw a football so hard at the chain-link fence that the ball would wedge into the tiny openings. His training group eventually had to pay a few thousand dollars to get it replaced.

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

A car company is on the clock for Young’s time on this mid-February day, asking him to work out and throw and just generally exist in the orbit of its new SUV, which is polished and buffed like heirloom silverware. There are more than 30 directors, camera people, producers, set designers and medics who chase people down for COVID-19 tests. There are enough organic protein bars and Uncrustable peanut butter sandwiches on a break room table to feed all of Young’s future teammates, wherever he may land in the upcoming draft.

Young walks into the cool California air and shakes everyone’s hand as if they’ve just handed him an envelope at his graduation party; it’s as if this entire commercial thing were just a passing cloud in his consciousness. Sometimes when a director asks him to throw a football he jokingly lurches forward and heaves the thing at the ground as if he’s doing it for the first time.

His parents, Craig and Julie, laugh nearby. No matter what, they will be nearby. When Bryce went to college at Alabama, they moved to a home about an hour from Tuscaloosa so they could cook him Sunday dinners and help him get away for a few hours of nonfootball conversation. They will eventually be in whichever NFL city he lands, after he has some time to acclimate.

They are a proof of concept for how love can smooth the rigors of an inherently unhealthy process. Attention, the loss of a private life and the birth of yourself as a brand and a business—Young has been living with those pressures for years. But now he is in the thick of NFL draft season, with its constant dissections and proddings by coaches, scouts and media. His whole life has been about becoming something. During this process he can hear, if he chooses, why many people think that goal is impossible. It’s more than typical predraft, poke-holes-in-a-prospect chatter. Young’s size makes him an easy target for criticism. He’s heard it so often that he just laughs about it.

At the combine Young measured in at 5' 10" and 204 pounds. There are 36 quarterbacks in NFL history who have played at least 50 games at six feet and 210 pounds or fewer. Eleven of them played in at least 100, most recently Drew Brees.

Jonathan Mailhes/Cal Sport Media/AP

Camp Bryce’s position: When you play well at every level despite these doubts, who cares? The NFL’s position, depending on which coach or evaluator you ask, varies. One longtime quarterbacks coach says that he long ago stopped paying attention to height. “Guys who feel throwing lanes and have spatial awareness, that’s the gift,” he says. One NFL offensive coordinator says of the film he watched on Young: “I loved his poise. He’s so calm and confident, which is really important.” One opposing NCAA offensive coordinator says that Young reminds him a bit of Chargers quarterback Justin Herbert stylistically, while NFL Network’s chief scout, Daniel Jeremiah, mentioned Brees before admitting that there was no clean comparison. Another evaluator said that Young takes hits really well, making him less of an injury risk than another quarterback considered smaller in stature, like Tua Tagovailoa.

Juxtapose those comments with the 24/7 draft news cycle, which has treated Young’s height a bit like leprosy. There were sportsbooks taking over/under bets on his combine weight. Before his weigh-in he told the assembled media, “I’ve been this size, respectfully, my entire life.”

Craig is a skilled mental health therapist, and Julie is one of those teachers you hope your kid lands with at school. Once, when a special needs student was brought into Julie’s special ed class midyear, the child’s occupational therapist warned Julie that the kid “doesn’t do a whole lot” and was basically limited to cause-and-effect toys. She smiled, nodded and, by the end of the year, taught the student the alphabet, how to type their name on a computer and how to sound out a few small words. Early on, when it was clear that Bryce was going to become a high-level athlete, his parents taught him the difference between conditional and unconditional love and attention. Out there? When you throw a pass, when you buoy a program, when you win the Heisman? That’s conditional. In here, where it’s just the three of us? That’s unconditional. That never changes. That needs to be enough.

So far so good, they think, though it doesn’t mean they dismiss the changing world around them. Young won the Heisman Trophy in 2021, and after the ceremony he went with his parents to a Knicks-Warriors game at Madison Square Garden. Steph Curry and his family invited the Youngs to hang out afterward in their suite. Julie says it stood out as a time she was really starstruck.

When recounting the story during a break in the commercial shoot, she asked a rhetorical question it would seem she already had the answer to.

How did we get here?

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

The family tells a story about one day when Bryce was just a few months old, wrapped in one of those Boppy nursing pillows. Craig would always drop a cloth football around the baby (he named the kid while watching Monday Night Football—he liked the ring of Bryce Paup, a Packers linebacker at the time), but this time, Bryce caught it. It was a stunning reaction for an infant; that kind of reflex usually develops around the 18-month mark. Craig jumped on the couch and celebrated.

The legend only grew from there.

When Bryce was 1, he could drill his mom with a football while she was loading the dishwasher. When Bryce was 3, he was running pickup games with kindergartners at aftercare. When Bryce was 4, he could recognize and read almost 200 words on his own. When Bryce was 5, he was scoring on a regulation 10-foot basketball hoop.

By the time Bryce was in eighth grade, he would greet almost every kid in his class individually. (He was already famous enough to have YouTube highlight videos, with remarks about his size so vitriolic that the comment section was disabled.) “In middle school, everyone is hyperaware of their social hierarchy standing,” says Danny Woo, Young’s eighth-grade science teacher. “They are either very insecure or trying their best to make themselves more secure than they really are. So no one is saying hello to anyone unless it’s their clique. But Bryce could work with anyone.”

Woo said that once he went to one of Young’s seven-on-seven games when Young was attending Cathedral High. The team had just defeated California powerhouse Mater Dei, and the first thing the quarterback did was walk up to the teacher and ask: “Mr. Woo, how is your Achilles?” They hadn’t spoken in months. Woo, who had been recovering from an injury, was blown away that Bryce would ignore a massive achievement in his life to ask about a teacher’s foot.

After his sophomore season Young transferred to Mater Dei—he was the first Black quarterback in program history—and spent one of his first spring practices getting hollered at by his position coaches. They told him to step up in the pocket. They told him to slide this way or that way. At a coaches meeting later that night Bruce Rollinson—one of the most successful high school coaches of his era, who has worked with the likes of JT Daniels, Matt Barkley and Matt Leinart—made a stunning declaration: “I said, ‘Look, guys, I don’t know where Bryce is going or what he’s doing sometimes, but every time he does something, magic happens. So, stop. Nobody coaches Bryce Young. Bryce is his own coach. Myself included. We’re all going to be cheerleaders now, because he’s going to make us look great.”

That fall, Young led Mater Dei to a state title.

Scott Varley/MediaNews Group/Torrance Daily Breeze/Getty Images

When Young was at Alabama, according to one of his coaches, he could see the field so well that the Tide scrapped a lot of their run-pass option concepts—plays that usually lead to open receivers and easier-to-digest defensive looks for developing quarterbacks—and installed more professional-style reads. The same coach says that Young was handed a thick packet every Sunday that detailed the entire game plan for the following Saturday. By Monday morning, he had it digested and would offer suggestions for altering protections and adjusting routes. When the QB’s time at Alabama was done, Bill O’Brien, the Tide’s offensive coordinator the last two years, told Kevin Pearson, Young’s old coach at Cathedral High, that the two smartest players he’d ever coached were Young and Tom Brady.

As Young wolfed down lunch one Saturday a few weeks back, dressed in a black T-shirt featuring Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant and LeBron James, he was relaxed. He was reminded of the stories of his fabled youth and was asked whether he’s bad at anything. “There’s a long list of things,” he said, eliciting laughs from his mom and grandmother, sitting nearby.

Like . . .?

“I want to learn how to golf,” he says. “I played Topgolf a few times and I was pretty bad at it. Anything involving swinging I’m really bad at. Baseball bats, golf clubs, it doesn’t look pretty. So, I want to get bigger into golf. I haven’t taken the steps to change that yet.”

Day 2 of the commercial shoot took over the Young family compound, a quaint Spanish-style stucco home with cream-colored accents, in Irvine. A crew arrived at 5 a.m. to start covering the entire floor in thick, carpeted mats. Cardboard is taped to the walls to prevent scuffing. The living room is rearranged, new furniture is brought in and sculptures are added to the table behind the sofa.

Young’s call time is not for a few hours, and for now the focus is on Craig and Julie. They have hair and makeup done and sit for hours of interviews (they, too, are in the commercial). In a small moment of respite, when the crew sets up for a different part of the shoot, Craig turns on one of his favorite songs, “Lovers Rock” by Sade, and dances.

They are, in these small windows, candidates for world’s most adorable parents of an elite quarterback. They are constantly laughing, making fun of each other and handing out compliments on how their sneakers match their outfits. Julie says they’ve been out to dinner when some of Craig’s old patients have walked up to thank him for his therapeutic work. Craig says that having Julie help him see the world has made him a better therapist and father.

All of this gets tested in real time when your son is born with a brain that processes like a chess bot and an arm that should be envied by military snipers. When you want to help him fulfill his ambitions while separating them from your own.

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

It hasn’t always been easy. When Bryce was in seventh grade, Craig had been coaching him hard for years, nurturing what they saw as a gift from God. Practice-field conversations about certain plays, missed opportunities or a lack of aggression here and there bled into home conversations. There was no way to tell where the coach ended and the dad began. Finally, Bryce went to Julie and said he didn’t like being around his dad anymore. Julie approached her husband with an ultimatum. Do you want to have a relationship with him, or do you want to be his coach?

“And that,” Craig says, “hurt me to my core.”

“I [was] dealing with my own stuff,” Craig says. “I didn’t reach my own potential athletically. I didn’t get the best coaching. There’s a chance I stopped playing because I quit, and I’m going to make sure that doesn’t happen to him. So if I saw weakness, or what I perceived to be weakness, I was going to yell it out of him or shame it out of him, coach him harder than I coached other players. And it was destroying his confidence and it put a wedge in our relationship.”

So Craig coached himself. Instead of screaming, “Why would you do that?!” after a missed throw, he’d say, “What did you see on that play, Bryce?” He’d ask the young QB what plays he liked to run, what made him comfortable in the offense. “I didn’t realize how much power my words—especially coming from a parent—had,” Craig says. “I started speaking positively. I told him there was no other quarterback I’d rather have in the world. No kid I’d rather be coaching. You’re the best. I know you’re going to make this play. Building him up.

“I wanted to make sure whatever he did was his choice. Do you want to work out today? Great. You don’t? That’s fine, too. Just let me know before I pay for it.”

Craig brings up Good Will Hunting, the 1997 movie starring Matt Damon and Robin Williams. Williams plays a psychiatrist, Sean Maguire, who at the movie’s climax finally breaks down the walls of Damon’s character, Will Hunting. Hunting was a genius who resisted treatment and shielded himself in his intellect, in part because he suffered traumatic abuse as a child. Maguire hugs Hunting, telling him, over and over, “It’s not your fault.” Hunting finally leaves his protective cocoon to search for happiness and chase down the woman he loves.

It’s a great movie moment—and entirely unrealistic. Craig’s point is that therapy is not like that. There are no quick fixes. It’s work. It’s coming back to the issue again and again. He found psychology as a second career after realizing, during a sales call hocking digital cable, that he was meant to help people. He put his tools and his expertise to work on himself, when he had to face his role in raising a wunderkind. He comes back to it, again and again.

Bryce would be on set soon. He lives a few minutes away now on his own. A representative from his agency asked everyone what they wanted for lunch, and Craig pored over the menu trying to select which type of fish and vegetables his son would like best. The energy would be familiar to any new empty nesters whose kids are coming back around.

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

My YouTube is the most random thing,” Young says, sitting on a sofa on the second floor of his family’s house, one of the few spaces that has not been overrun by the film crew. There is a corkboard wall with family photos new and old, and enough shoeboxes to build a toddler village. “It’s literally anything.”

This is how he unwinds. Right now, he likes watching videos about ancient battles. “I’m not even a history guy,” he says. “I’ve gone through all the Roman leaders and stuff. I think I just like learning random things.”

It’s not hard to see why almost all of Young’s coaches say teammates instantly take to him. Having a conversation with him is like resettling on solid ground after riding a roller coaster. Which is ironic, because right now he’s living in world that’s largely out of his control. ESPN draft analyst Todd McShay said in February that the idea of drafting Young would “scare me to death,” despite noting that he was “special.” A few weeks later, he called Young a miniature Patrick Mahomes. Jeremiah, the NFL Network scout, said that if Young were 6' 3", people would be talking about him the same way they did Trevor Lawrence. Pearson, one of Young’s high school coaches, said he heard an analyst on the radio say that he wouldn’t draft Young because, “I like my quarterbacks bigger than my kickers.”

“I think, even if someone has a negative opinion of me, they can still know what they’re talking about,” Young says. “At the end of the day, it’s an opinion. I don’t play to win over the hearts of others. I play for my family, for my teammates, for the people who are showing up every day and put in the work. There’s plenty of experts, but there are no experts who get everything right. You could get 99% of it right, but the one you got wrong, it doesn’t mean you don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Young’s favorite class at Alabama was social psychology, which, he says, helped him to “self-reflect on how you’re processing things socially and also how others perceive things and tend to act socially.” He called it “really applicable.”

While there are some in Young’s orbit who think he has harnessed all the slights and jokes and memes of him standing next to taller people as some kind of renewable energy source, the truth seems less exciting. Through this process, through an understanding of conditional and unconditional love, through his own explorations as a psychology major, which have helped him develop his own worldview, Young has tried to make the noise around him a nonfactor.

Rollinson, Young’s coach at Mater Dei, says the angriest he ever saw the QB was a game where the opposing team came out in Cover Zero, a defense elite quarterbacks can pick apart because it places almost all receivers in man-to-man coverage in exchange for more pass rushers. Young told Rollinson it was “disrespectful” and put up 21 points in six minutes. Rollinson asked him when Mater Dei could call off its passing game and stop embarrassing the other team. Young responded coolly, “As soon as they get out of Cover Zero.”

When people describe Young this is the version that often comes up. It’s not a brashness. It’s not a lack of emotion, but it’s not an overabundance, either. He can lose himself in a celebration; after he scored the winning touchdown for Mater Dei against the No. 1 team in the country, IMG Academy, he shoulder-bumped a receiver so hard that he was knocked down. Or, he can simply nod his head or flip the ball to an official after leaving the crowd with mouths agape.

Young can talk with confidence about his own evolution alongside that of his parents, almost as if he can psychoanalyze himself. Even during the difficult times, before they instituted the rule that after 10 minutes of postgame discussion he and his dad would dead-bolt anything resembling sports (“that helped a lot,” Bryce says), there was something to take from the process. Like when Bryce was young and in love with basketball. He wouldn’t shoot. Not in a Ben Simmons kind of way, but because he thrived on setting up his teammates. He liked to distribute the ball. “I was the opposite [of most kids],” Bryce said. “[My dad] would have to try and get me to shoot more. And it wasn’t because he wanted me to be the star or whatever, it’s because I just didn’t shoot at all. I would always be trying to pass it.

“I think, naturally, that’s [how I am]. It was knowing that he had confidence in me, but he was also holding me accountable. He did a good job of those two.”

Bryce says of their relationship: “The best part was being able to get over the hump of [the fighting] being over. There was definitely a change. There was a lot more [times] where we were able to have a normal father-son relationship.”

He says he values his family, especially as life changes, as his personal business grows—Bryce’s college coach, Nick Saban, famously told an audience at a speaking engagement that the quarterback had earned nearly $1 million in NIL money before taking his first snap in college—and as there become fewer and fewer opportunities to decompress and learn about Roman battles on YouTube.

Young says he appreciates his parents just “being able to be around. We never talk about anything seriously football-related. Ever. Our conversations are about shoes or clothes, normal stuff. Being able to do that, our interactions haven’t changed at all.”

Butch Dill/AP

The director calls for Bryce to go through his routine on the field.

For those who have seen a quarterback preparing to throw, it’s usually a parade of banalities. Little steps forward with weightless blue balls in each hand, waving them back and forth like one of those maneki-neko cats. Half-speed shuffles and soft tosses.

Still, Craig and Julie are watching. Smiling. Julie is wearing the first pair of sneakers Bryce ever bought for her, a pair of Nike Dunks in Easter colors, pinks and light blues, greens and purples. She’s pocketed Bryce’s iPhone and Chapstick for him, honoring a parent’s most sacred duty: holding things your kids don’t want to hold anymore.

Craig is telling someone this next drill is called “The Elvis.” Bryce swings his throwing arm around and around, like the King singing “Blue Suede Shoes.” Outside, the air is a bit cold. People are hunched over waiting for the California sun. There is supposed to be complete silence. Bryce is facing north toward the street, toward the houses, toward the gigantic mountain range towering off in the distance.

His parents say that if their son was a concert pianist, they would be at piano practice. If Bryce wanted to be a ventriloquist, they would be sitting in the front row, watching a puppet tell them jokes.

There is no formula. Great quarterbacks come from everywhere and nowhere. Some are troubled and some are calm. Some have idyllic childhoods and some are overcoming a tortured existence through football. Some have overbearing fathers and stage moms, and some have no fathers or mothers at all. Some come from homes and some spend their lives searching for one.

But it’s hard not to wonder about what is happening here. It’s hard not to try to quantify it. Julie asked how they got here, and maybe it’s simply because they never left. They made here wherever it needed to be. They never stopped trying. Instead of making their only son a project and a showcase, instead of treating him like a football robot or a piece of emotionless equipment, they allowed themselves to go for the ride, to be changed, to grow just like Bryce grew.

So no, they say, this never gets old even though they’ve seen it a million times.

Bryce drops back, whistling a pass to the same quarterbacks coach he’s had for years. The ball doesn’t blast out of his arm like a rifle so much as it travels like a drone with its coordinates already punched in. It lands where it needs to be.

Dad approves. “I love watching him throw,” he says.