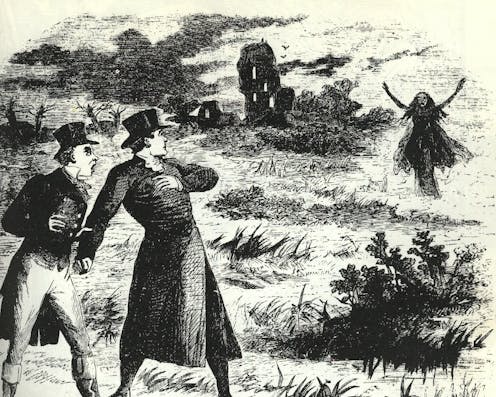

Enter a mysterious, enchanting world where a handsome prince steps out of the belly of a cat; where a black horse blocks the night traveller’s way at every turn; where a vintage bottle of wine is presented as an aid to getting into heaven. This is the world of the folktale, and happenings like this are not unusual.

These scenes, and hundreds of others like them, are scattered through the narratives of the recently published anthology The Midnight Washerwoman and Other Tales of Lower Brittany. The stories, originally collected in the 19th century by François-Marie Luzel (1821-1895), have been edited, translated and introduced by British folklore expert Michael Wilson.

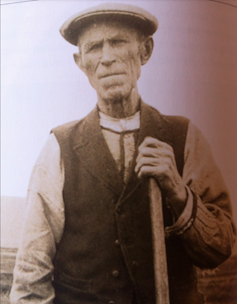

Luzel would spend the long winter evenings listening to folktales told by his neighbours who were local Breton villagers and farmers. These social gatherings were known as veillées, and Luzel wrote down the tales in considerable detail, preserving a storytelling tradition that is now almost forgotten.

Finding common ground

Luzel was a farmworker who, with the help of his sister Perrine (1829-1915), collected folklore from around 70 storytellers in Brittany, recording their names, professions and where they came from. He was almost unique among folklore scholars in the 19th century in the attention he gave to the storytelling event as the context of the narratives.

In Brittany as in Ireland – where I lecture in Irish folklore – oral narrative was enriched by two language traditions – in this case Breton and French, and in my country, Gaelic and English. Wilson has used the Luzels’ accounts of storytelling evenings to gather 29 stories, many translated into English for the first time and presented in a series of five imaginary veillées.

Most of the narratives in the book can be identified according to the International Index of Tale-Types. This list of stories compiled in the early 20th century by Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson, and later updated in 2004 by Hans-Jörg Uther, classifies folktales from around the world according to their subject matter. This ATU index is a useful tool for comparing stories that existed – and still exist – in different regions, cultures and languages around the world.

Wilson notes the importance of the washerwoman as a supernatural being in Breton folklore, closely related to the bean nighe in the Scottish tradition, and the bean sí in Ireland. The story François Thépault of Botsorhel told Perrine Luzel in 1890 is a version of tale-type ATU501, The Three Old Women Helpers. This is one of a group of stories where disquiet around women’s work – especially when carried out alone and late at night – is portrayed.

This was a very popular story in Irish tradition, with nearly 100 versions collected in the 19th and 20th centuries. In it, sinister old women arrive at night while the woman of the house is working alone. They help her by spinning industrial quantities of yarn, but at some point it becomes clear that they are going to kill her and eat her.

In Thépault’s version, the woman’s husband gets up and together they manage to lock the visitor out. More than 100 years later, in 2001, a version which is similar to Thépault’s was recorded from the west Kerry storyteller, Bab Feiritéar (1916-2005).

In Feiritéar’s story, there are seven old women, and the woman of the house gets rid of them by shouting that the nearby fairy hill is on fire. This incident, a feature of many Irish versions, shows a strong link between this story and fairy belief connected with the local landscape.

Some stories illustrate the worldview of the community, and could be seen as philosophical discussions of life and death. In The Two Friends, also collected from François Thépault in 1890, a young man’s best friend comes back from the dead three nights in a row, and gradually leads the young man to his own death. This is portrayed as a happy outcome, as it means the friends are reunited.

However, a strong belief in the afterlife did not preclude a delight in outwitting the clergy, as is illustrated in The Priest of Saint Gily, told in Breton by Catherine Stéphan in Plouaret in 1892. Here, the priest’s cow is stolen, and when the priest brings the thief’s child into the pulpit on Sunday to tell the congregation the truth, the child has been coached by his father to falsely accuse the priest of a relationship with his wife.

When the priest protests his innocence, the thief says: “But Father, you started by assuring us that everything the child was going to say was true and that nothing but the truth was ever spoken from the pulpit of truth!”

The Miller and his Seigneur, told by one of Luzel’s most prolific tale-tellers, Barba Tassel in Plouaret in 1868, shows a similar satisfaction in the humiliation of high-status members of the community. From the same storyteller, there are two versions of ATU425: The Search for the Lost or Enchanted Husband, in the fifth veillée.

In this story the husband is trapped in an enchanted form – such as a toad – and can only be freed by his wife. This involves a reversal of the enchantment and eventual vindication of the female protagonist.

Tassel’s version is similar to that of the south Kerry storyteller Seán Ó Conaill, whose version of ATU425, The Black Crow, was collected by the Irish Folklore Commission in 1925. Like the fisherman’s sweater, spreading among north Atlantic communities in the same period and resulting in unique cultural products such as the Aran and Fair Isle versions, it is not hard to imagine stories being exchanged, developed and elaborated in a similar way through cultural contact.

The potential for comparative research in this area is significant, though Wilson resisted venturing into this area because he wanted the book to appeal to a wide readership.

He has succeeded. The book is delightful: always lively and interesting, but also dreamlike, intriguing and thrilling by turns. It is a pleasure to read, beautifully illustrated by Caroline Pedler, and has plenty of material for those who wish to explore these tales further.

Síle de Cléir does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.