Few falls from political grace have been as abrupt and as vertiginous as that of Boris Johnson, ousted from 10 Downing Street little more than three years after his arrival.

Elected on a wave of enthusiasm from both Conservative party members and MPs, Johnson initially seemed an unstoppable phenomenon – one of those rare politicians not only instantly recognisable to the public but also liked by large swathes of them, sparking enthusiasm among constituencies formerly unattainable to the Tories.

Promising to take the UK to the fabled “sunlit uplands” of Brexit, he presented himself – and was accepted by many voters – as a “fresh start”, somehow unconnected to the years of austerity under David Cameron and the tortured agonies of Theresa May’s time in charge.

He saw himself as a historic figure, like his hero Winston Churchill, whose premiership would be remembered as a pivotal moment for the resurgence of Britain as a global force. As recently as last year, he was letting it be known that he expected a decade or more at No 10. Now he departs after a tenure only a few weeks longer than Ms May’s and half the length of his former Oxford chum Cameron’s, a diminished figure rejected by his own MPs and much of the electorate, with little to show for the grand promises he made.

Those promises were on full display in his first speech as prime minister on the steps of Number 10, after returning from the Palace on 24 July 2019. Vowing to prove “the doubters, the doomsters, the gloomsters” wrong, he boasted that his government would allow the UK to recover its “natural and historic role” as a “truly global Britain” by delivering on the Brexit vote he did so much to ensure three years earlier. On top of this, he promised more police on the streets, more hospitals, a plan for social care, levelling up all parts of the UK and a stronger union between the “awesome foursome” of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Despite this inclusive tone, Johnson immediately took a knife to the cabinet inherited from May, forging a new government leaning heavily to the Eurosceptic right. Vote Leave supremo Dominic Cummings was brought to the centre of power as the PM’s top adviser amid a phalanx of veterans of the referendum battle in No 10. Cummings set the course for a campaign of outright confrontation with Brussels, with parliament and moderate members of Johnson’s own party, using the threat of a no-deal Brexit to try to force agreement by the PM’s self-imposed deadline of 31 October.

Without a majority in the Commons, and with more than half of MPs firmly opposed to no-deal Brexit, Johnson caused uproar by asking the Queen to prorogue parliament, preventing MPs from returning to Westminster to block his plans. In an unprecedented ruling, the Supreme Court found on 24 September 2019 that the prorogation was illegal, making Johnson the first serving PM found by a court to have broken the law and exposing him to accusations of lying to the Queen. MPs passed a law forbidding the PM from taking the UK out of the EU without a deal, leading Johnson into an abortive attempt to call an election.

In a move to purge Tory ranks of Europhile voices, he expelled 21 rebel MPs – including big beasts like Kenneth Clarke, Philip Hammond and Amber Rudd – and declared that all future election candidates must be signed up to Brexit. Despite saying he would “die in a ditch” rather than extend negotiations, he eventually accepted a delay. And he finally secured his deal, after last-ditch talks with Irish Taoiseach Leo Varadkar at a hotel in the Wirral, by caving into Brussels over a customs border in the Irish Sea – something he had said he would never accept.

The adoption of the Northern Ireland protocol allowed Johnson to call a snap election in December 2019 on the platform of an “oven-ready deal” to get Brexit done, but he later turned against it, threatening legislation to overrule it at the risk of a trade war with the EU. He was in his element in a campaign which was heavy on stunts – with Johnson driving a bulldozer through a wall symbolising the Brexit “gridlock” – but light on submission to media scrutiny, as he dodged heavyweight interviewer Andrew Neil, and at one point hid in a fridge to avoid a TV reporter’s questions.

Aided by the growing unpopularity of Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn, he secured a landslide 80-seat majority in the Tories’ best result since 1987. His personal charisma seemed to have transformed the UK’s political landscape, with the decades-old Labour allegiance of “Red Wall” seats like Redcar, Bolsover and Sedgefield melting away. Victory allowed him to brush aside all opposition to Brexit, which formally took effect on 31 January 2020, hailed by Johnson as “the dawning of a new era” and sealing his legacy in the history books – for good or for ill.

It was followed a year later by a trade deal with the EU, again secured by a last-minute cave-in to Brussels demands (this time on fisheries). Its terms were so unfavourable to the UK that the government has not yet been able to implement them in full, allowing European companies an automatic advantage over UK exporters in cross-Channel trade.

Meanwhile, Liz Truss toured the world, signing dozens of trade deals which did no more than replicate terms already enjoyed as a member of the EU. The few new deals she sealed were worth, by the government’s own estimation, only a tiny fraction of the 4 per cent hit to GDP from Brexit, and have caused consternation to farmers fearful of being undercut by cheap Australian and New Zealand produce.

The prime minister’s “world king” phase reached its pinnacle three days after the date of Brexit with a speech in Greenwich in which he evoked the spirit of the seafaring 18th-century builders of empire to declare Britain the “supercharged champion” of international trade. Viewed from today, with British exporters mired in new red tape, queues at the ports and trade with Europe slumping, the speech appears dripping with hubris. All the more so because the date of Brexit coincided exactly with the arrival in the UK of the other issue set to define his premiership – Covid-19.

The prime minister’s ‘world king’ phase reached its pinnacle three days after the date of Brexit

At Greenwich, Johnson breezily declared that while others may panic, the UK would “take off its Clark Kent spectacles and leap into the phone booth and emerge with its cloak flowing” to resist limits to its freedom in response to the novel coronavirus. And this insouciance continued even as it became chillingly clear that the threat of worldwide lethal pandemic was all too real.

With images flooding in of Covid patients struggling for breath in Italian hospital corridors, the PM airily boasted of shaking hands on the wards and refused to shut down “superspreader” events like the Cheltenham Festival. Cummings has claimed that it took an intervention by officials terrified by data suggesting the NHS would soon be overwhelmed to persuade Johnson to shift from a “herd immunity” strategy.

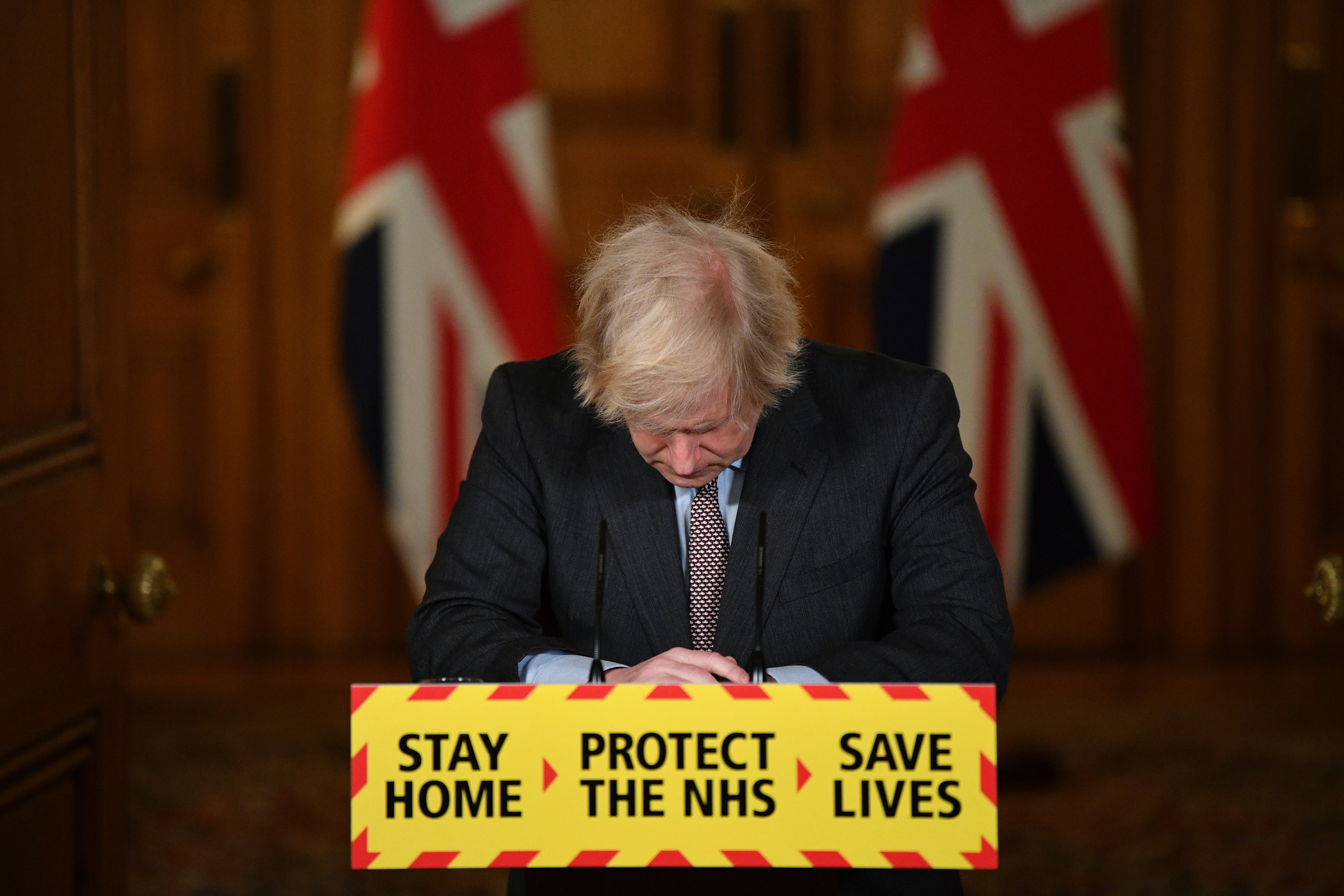

By the time the first national lockdown was announced on 23 March 2020 – several weeks too late, as many experts believe – Covid was in all corners of the UK and the public was already voluntarily isolating themselves, staying away from crowded places and taking children out of school. Throughout lockdown, it was clear that the PM felt deeply uncomfortable to be responsible for the most draconian restrictions on personal liberty ever inflicted in the UK outside wartime. Flanked by the grim and determined faces of medical and scientific advisers Chris Whitty and Patrick Vallance in daily televised press conferences, he appeared visibly to be suppressing his natural ebullience, which spilled forth in predictions that Britain could “turn the tide” on Covid in just 12 weeks.

It was his own brush with death which drove home to him how serious the situation actually was, as he contracted Covid on 27 March and spent three days in intensive care as NHS staff fought for his life. Any sympathy for the PM evaporated as it emerged that Cummings too had caught the disease and responded by driving his family across the country to County Durham in defiance of stay-at-home restrictions. Johnson’s refusal to sack his adviser, who faced ridicule as he claimed to have visited beauty-spot Castle Barnard “to test his eyesight”, undermined public confidence in official instructions.

During all this, Johnson’s partner Carrie gave birth to their first child together, Wilfred, believed to be the PM’s sixth from a series of relationships. The couple later married in a secret ceremony at Westminster Cathedral in May 2021 and had a second baby, Romy, in December.

Personality clashes between Carrie and Cummings were blamed for the dramatic resignation of the PM’s right-hand man in November 2020. His departure did little to allay Tory MPs’ concerns about chaotic operations at No 10, and the former adviser went on to lambast Johnson as “the trolley” in a series of lacerating statements depicting a directionless prime minister veering from policy to policy under the influence of whoever he had last spoken to. Cummings told MPs he had heard the PM say he would rather see “bodies pile high” than go into a third lockdown in late 2020 – something which Johnson flatly denied.

Relief came with the release of vaccines against Covid-19, rushed into deployment by a taskforce led by Kate Bingham, with the world’s first shot of the Pfizer jab received by 90-year-old Margaret Keenan in Coventry on 8 December 2020. But successive waves of Covid saw restrictions maintained until 19 July 2021. “Freedom day” was a muted affair, with case numbers still high, and there was bitter debate within cabinet before Mr Johnson confirmed there would be no Christmas lockdown that winter.

The PM tried to establish his credentials as a world statesman, hosting the G7 in Cornwall and throwing his weight behind calls for net-zero carbon emissions at the Cop26 summit in Glasgow in November 2021. But high hopes from the environmental gathering were undermined by a last-minute ambush by China and India to water down the phase-out of coal, leaving chair Alok Sharma in tears.

The nation was still emerging from the privations of pandemic and working out how to pay off the £400bn bill for furlough and other support schemes when another crisis exploded onto the world stage, as Vladimir Putin sent the Russian army into Ukraine. Despite having overseen a defence and security review which focused on cyber-security and terrorism, and despite having told MPs in November that “big tank battles on European land mass are over”, Mr Johnson was swift to recognise the need to supply Kyiv with heavy weaponry to resist its belligerent neighbour. But even as he burnished his Churchillian self-image with a series of visits to president Volodymyr Zelensky, the seeds of his downfall were being sown with a wave of revelations of parties and social gatherings at Downing Street during lockdown.

Public anger was fuelled further by Johnson’s insistence that no social distancing rules were broken. Those claims are now subject to a probe into whether he misled parliament which could set the seal on his battered reputation. Doubts over his integrity had already been sown by the Wallpapergate row over the lavish refurbishment of his Downing Street flat, his attempt to save pal Owen Paterson from punishment for sleaze and the resignation of an ethics adviser after the PM overruled his bullying finding against Priti Patel. A second standards adviser, Lord Geidt, quit in June in protest at the government’s willingness to break international law.

As Johnson was fined by police and forced to apologise, his MPs – panicked by seismic by-election revolts in formerly “true blue” Shropshire North and Tiverton & Honiton – queued up to submit letters of no confidence. He survived a vote in June, but 148 of his MPs (more than 40 per cent of the total) backed the effort to remove him.

And his fate was sealed just a month later, when the resignations of Sajid Javid and Rishi Sunak prompted a slew of ministers to walk out. The final straw was Johnson’s denials – which he ordered ministers to repeat on air but were later proved untrue – that he had known of concerns over the conduct of Christopher Pincher before the deputy chief whip quit.

Contrary to fears that he would use his remaining weeks in office to cause “carnage”, Johnson seemed to view his ejection as an excuse to put his government into “zombie” mode and go on holiday. Despite efforts to bolster his legacy with announcements on nuclear power, broadband and submarines in his final week, the image of the PM on the beach during a cost-of-living crisis is more likely to stay in the public mind.

He leaves office with Britain facing deep recession, families fearing destitution and thousands of businesses on the brink of closure due to sky-high energy bills. His levelling up plans seem little more than a slogan after the cancellation of key rail links in the North, his promised 40 new hospitals – most actually refurbishments or new wings – are mostly unbuilt, and the future of his net zero plans look in doubt under his likely successor.

He will be remembered for delivering Brexit, but that may come to be seen increasingly to be a black mark on his record if the promised benefits fail to materialise. If he’s lucky, he’ll be remembered more for vaccinating the nation against Covid than for exposing thousands to the disease through delay. It all seems a far cry from the heroic visions and optimistic bluster which propelled him to power in the first place.