The words of the Old Testament prophet Isaiah rang out across the crowd at the election rally, amplified by a huge loudspeaker array: “Those who strive against you shall be as nothing and perish . . . For I, the Lord your God, hold your right hand . . . Fear not, I am the one who helps you.”

The evangelical pastor on stage at the showground in Montes Claros finished his Bible reading. To roars of approval from thousands of supporters dressed almost entirely in Brazil’s national colours of green and yellow, he presented the holy book to the man to whom the reading was dedicated: President Jair Bolsonaro.

“He is the captain of the people, he will win again,” played a jingle insistently, as images of the young Bolsonaro wearing his army uniform flashed up on giant screens either side of the stage. “He is from God, you can trust him”.

On stage with Bolsonaro as he campaigned for re-election in Brazil’s run-off presidential vote on October 30 was a cross-section of his conservative coalition: an army general standing as his running mate, a successful businessman just re-elected as governor here in the key election swing state of Minas Gerais, and a YouTube musician-turned-senator.

All had the same message: Brazil was at a critical moment in its history and Bolsonaro must not lose to his challenger, the leftwing former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, usually known simply as Lula.

“We cannot allow Brazil to turn into a disaster like Venezuela,” said Humberto Souto, a veteran national politician who is mayor of Montes Claros, the main city in the poorer north of Minas.

While Lula’s international reputation still reflects his government’s efforts to reduce poverty, Bolsonaro supporters talk only of the corruption which marred the leftwinger’s time in office, later triggering what the US justice department called the largest foreign bribery case ever. “Lula’s a thief, the only place for him is jail,” chanted the crowd at the rally.

As Brazilians prepare to vote in the second-round run-off on Sunday, Lula remains the narrow favourite in polls, though Bolsonaro is closing the gap and first-round surveys understated his support.

Whether he wins or loses, Bolsonaro has demonstrated in the election that he has forged a durable rightwing movement, one that blends Brazilian conservatism and nationalism with American-style culture war politics and battles waged over social media.

“Bolsonarismo has strong roots in society,” says Camila Rocha, a researcher and author of a book on the president. “[Even if he loses] he will be able to keep the movement going because he will have a lot of money and I think he will try to come back in four years.”

The persistence of Bolsonarismo

If the “Trump of the tropics”, as the international media labelled Bolsonaro, was initially dismissed by opponents as a political aberration, the speakers at the rally in Montes Claros demonstrated his staying power.

The pillars of his coalition are the fast-growing evangelical churches, the army and police, farmers, business, and a new generation of socially conservative YouTube musicians and influencers.

As a result, Brazil’s election with its emphasis on religion, nationalism and cultural norms feels different to other recent presidential contests in South America. In Colombia, Chile and Peru, social justice, equality, poverty and the environment came to the fore and voters swung against a ruling elite widely perceived as self-serving and out of touch.

In Brazil, however, Bolsonaro has successfully kept up an anti-establishment message even while in office, railing against institutions such as the Supreme Court or the mainstream media which he believes are biased against him and cultivating a simple, man-of-the-people image.

He is partial to riding his motorcycle, stopping off in small towns for a pastel, a deep-fried fast food snack. More recently, his tours have turned into massive mobile campaign events, with thousands of supporters bedecked in Brazil’s national colours joining him on two wheels.

This is the image that is resonating with his base and helping to narrow the gap with Lula before Sunday’s decisive second-round vote. A poll last week by Datafolha suggested the former leader has 52 per cent support versus 48 per cent for Bolsonaro — a technical tie, given the margin of error of two percentage points up or down.

“The left did nothing for us and left the country in a mess,” says Ana Tulia Flores, a young law student attending the Montes Claros rally. In the last presidential election in 2018 she had voted for Lula’s Workers’ party (PT) but now she was backing Bolsonaro.

“There is less economic crisis,” she says. “Most of our population is Christian. We need a president who will defend the principles of God and the family.”

Lula, who governed Brazil from 2003-10 during a commodity boom, has assembled a broad coalition of parties against Bolsonaro but critics say he has run a lacklustre campaign which lacks fresh ideas. A former metalworker whose family left the struggling north-east to seek a better life in São Paulo state when he was seven, Lula retains strong support among Brazil’s poorest, trade unionists and most of the intelligentsia and world of culture.

But among the 100mn Brazilians in what the national statistics agency IBGE defines as the biggest social class — broadly, the skilled working class and lower-middle class, which expanded under Lula — Bolsonaro is building an advantage.

“Bolsonaro’s libertarian thing makes sense for some of these people,” says Rocha. “Many are informal workers, gig-economy workers. A lot of them think, ‘I don’t want to pay taxes’, and ‘I want to be my own boss’.”

The populist president’s socially conservative coalition has put down deep roots in the country’s vast interior in the booming agribusiness sector, which now accounts for nearly 30 per cent of gross domestic product, as well as in the more developed south and south-east of Brazil.

Bolsonaro-supporting candidates scored major successes in elections for congress and state governors on October 2, which coincided with the first round of the presidential race.

In the congressional races, Bolsonaro’s Liberal party were the big victors. They jumped from seven to 13 seats in the 81-member Senate, where they will be the biggest party, and from 76 to 99 seats in the 513-member lower house. In Brazil’s highly fragmented political system, with 23 parties represented in the next legislature, that counts as a significant success.

Among the Bolsonaristas elected was Cleitinho Azevedo, a 40-year-old YouTuber and former musician from Minas Gerais who joined the president on stage in Montes Claros sporting a camouflage cap and football T-shirt.

“It’s no good [me] being elected with 4mn votes if Jair Bolsonaro is not also elected,” he told the crowd, who broke into chants of “Brasil Bolsonarizou” (Brazil has become Bolsonaro-ised).

Bolsonaro allies also won or are poised to win the powerful governorships of Brazil’s three most populous states accounting for 40 per cent of the country’s population: São Paulo, Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro.

“Many from the extreme right, several ministers and former ministers, managed to get elected for the first time,” says Maria do Socorro Braga, a political scientist at the Federal University of São Carlos. “It was a show of strength from Bolsonaro. Especially in the Senate and Chamber [of Deputies]. It is a much more conservative Senate.”

‘Things are moving forward’

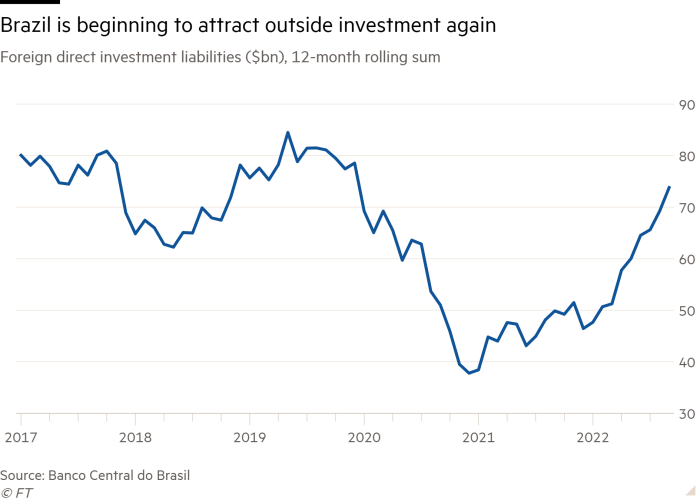

Bolsonaro is being helped by a better than expected economic performance. Brazil’s GDP is expected to grow by 2.8 per cent this year, according to the IMF, not far short of China. It rebounded fully from the pandemic last year and foreign direct investment shot up to $74bn in the year to September from $50bn a year earlier, according to the Brazil central bank. The headline inflation rate peaked at more than 12 per cent in April but fell to 7.2 per cent in September and many business leaders remain bullish on the president.

“Bolsonaro’s government has done a lot of reforms, pro-business, pro-development reforms,” says Mauricio Russomanno, president and chief executive of Unipar, a large São Paulo-based chemicals manufacturing company. “His [economic] team is very well perceived . . . Things are moving forward. We have economic growth and some level of stability . . . Infrastructure and agribusiness are doing very well.”

The business arguments resonate strongly with Romeu Zema, who ran a family retail chain before entering politics and winning election as governor of Minas Gerais state in 2018. Re-elected this month, he was happy to share the stage with Bolsonaro in Montes Claros despite not agreeing with some of the president’s more extreme ideas, such as his promotion of unproven remedies for Covid-19, which has claimed more than 680,000 lives in Brazil.

“I know the president close up,” Zema tells the Financial Times, waving aside oft-expressed concerns from opposition and civil society leaders that Bolsonaro represents a threat to democracy or institutions. “He is a verbally impulsive person . . . But he doesn’t act in the same way. I am not defending him. I have many differences with him . . . I think he got various things wrong.”

However, the PT was far worse, he says, because its 14 years in power ended with Brazil in its worst recession since modern records began 60 years ago. He compares what the party did to Brazil to an athlete taking steroids. “You will boost your muscles, win medals, win the Olympics and become famous, but in 10 years you will have kidney, heart and liver problems and become impotent”.

Bolsonaro has also moved to expand his appeal among the poor. The president’s programme of cash handouts for poorer families has been expanded for the election year in what opponents decry as blatant electioneering which risks worsening the government’s shaky finances. The president persuaded Congress to circumvent a constitutional cap on spending to expand his signature welfare programme, Auxílio Brasil.

Bolsonaro’s government now claims it is the “largest income transfer programme in the world” and the message is constantly hammered home to voters. “600 reals — Bolsonaro pays more,” flashed the message on the giant side screens at the Montes Claros rally.

The outrage often expressed in Europe or the United States over Bolsonaro’s crude and at times misogynistic language and his politically incorrect comments resonates less in Brazil, say analysts, particularly among the less educated.

“Everyone in Brazil has someone like Bolsonaro in their family or in their circle of friends,” says Oliver Stuenkel, professor at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in São Paulo. “He’s like the uncle from the interior who’s flipping the patties on the barbecue and ranting as he does so.”

Bolsonaro’s attacks on environmentalists and robust defence of Brazil’s right to develop land in the Amazon rainforest are popular among those Brazilians who resent foreigners telling them how to run their country.

His expletive-filled outbursts and colourful personal life, with three marriages and two divorces, have not stopped him painting himself successfully to his supporters as a defender of family values and winning support from evangelicals, who see Lula and the left as a greater threat.

At his rallies, allies make a point of introducing the 67-year-old president by his full name, Jair Messias Bolsonaro — his middle name means “Messiah”, the anointed one or saviour. Bolsonaro was raised as a Catholic but rebaptised in the river Jordan by an evangelical pastor, giving him identification with both communities. He described Minas at the rally in Montes Claros as the state where he was “born again”, a reference to his surviving a near-fatal stabbing during the 2018 campaign.

The conservative right is now resurgent after years of leftwing dominance, says Marco Feliciano, an evangelical pastor and federal lawmaker for Bolsonaro’s Liberal party. “Social media . . . freed us from the monopoly of the mainstream media, and together with the evangelicals, we turned things around. The icing on the cake was the election of President Bolsonaro.”

Bolsonaro’s tough law-and-order message plays well in a country convulsed by violent crime. His campaign adverts constantly play up Lula’s time in jail on charges of personally benefiting from corruption, although those convictions were later annulled by the Supreme Court. They also attempt to paint the leftist as the preferred candidate of criminals and drug dealers.

The president’s authoritarian tendencies, as a former army captain who has in the past praised Brazil’s 20th century military dictatorship, help explain his appeal to the military. Choosing Walter Souza Braga Netto, a reserve army general, as his running mate has cemented it further.

A holy war

As the election battle narrows in its final stages and the fight becomes ever more brutal, Lula’s early lead over Bolsonaro has shrunk and he has been forced on to the defensive. With the PT much less popular than he is, the former president has started to adopt white, rather than the party’s traditional red, as a campaign colour.

After earlier supporting the legalisation of abortion, Lula has stressed he personally opposes the procedure. On October 19 he released a long open letter to evangelicals stressing his Christian faith and pledging religious freedom, and he has joined church prayer gatherings.

Although religion played little part in presidential elections across South America over the past two years, it has taken centre stage in Brazil’s campaign, leading some commentators to speak of a “holy war” between Bolsonaro and Lula in which each candidate invokes God on their side and paints the opponent as the devil incarnate.

This territory favours Bolsonaro. Brazil’s once dominant Catholic church is in sharp decline, its appeal eroded by the rise of evangelical churches. While most of the shrinking Catholic population favour Lula, according to opinion polls, Bolsonaro enjoys a clear advantage among evangelicals.

Whether Bolsonaro’s conservative coalition is big enough to win him the election remains in doubt. The incumbent has been drawn into a series of controversies in recent days, notably on Sunday when a political ally fired shots and threw a grenade at police who were upholding a court order for his arrest. Two officers were injured in the attack, which undermined Bolsonaro’s law and order rhetoric.

Most pundits still believe Lula will win, but few are now ruling out a surprise Bolsonaro victory. If Lula does triumph, the 76-year-old faces an uphill battle against a hostile congress and a strongly motivated Bolsonaro base.

“Even if Bolsonaro loses the election, he will have allies in São Paulo, Rio, Minas Gerais and the south ,” says Rocha, the Bolsonaro expert.

Montes Claros and the state in which it lies, Minas Gerais, encapsulate the dynamics of the election. Since 1950 no president has won Brazil without winning Minas, a state bigger than France which includes an industrial and prosperous core, a prosperous agricultural west and a poorer mainly rural north.

In the first round, both city and state voted by narrow margins for Lula but locals say the mood is shifting. Governor Zema says his private polling now indicates that Bolsonaro has drawn level in the state and Lula has cancelled appearances in the north-east to make fresh stops in Minas in the final days of the campaign.

“Politics changes very easily around here, depending on how the wind is blowing,” says Paulo Narciso, a veteran journalist who runs Radio 98FM, the local station in Montes Claros. “Here the same voter who elected Lula [in the past] elected Bolsonaro last time.”

“But what really worries me is that now the country is deeply divided. Brazil is oscillating between the ideologies of left and right and ending up with the disadvantages of both.”