Fuel cells seem to be the solution to every problem that everyone has ever had with an EV. They'll do upwards of 400 miles on a tank, refuel in only a few minutes, and use about 90 percent less heavy metals than an EV.

So what's the problem? The problem is the fuel. There are literally more Tesla Superchargers in San Francisco alone than there are hydrogen stations in the entirety of the U.S. Mercedes-Benz, Toyota, Honda, Hyundai, and plenty of others have been showing off fuel cell cars for decades, none of which have gone into mass production. But BMW still has faith, and after driving the company's new hydrogen-powered iX5, it seems like H2's time might finally be here.

GAS-POWERED

Hydrogen itself can be produced in a number of ways, some more environmentally conscious than others, but in an ideal world the stuff can be pulled straight out of water by a process called electrolysis, where renewable energy (typically wind or solar) is used to split the H from the O, emissions-free.

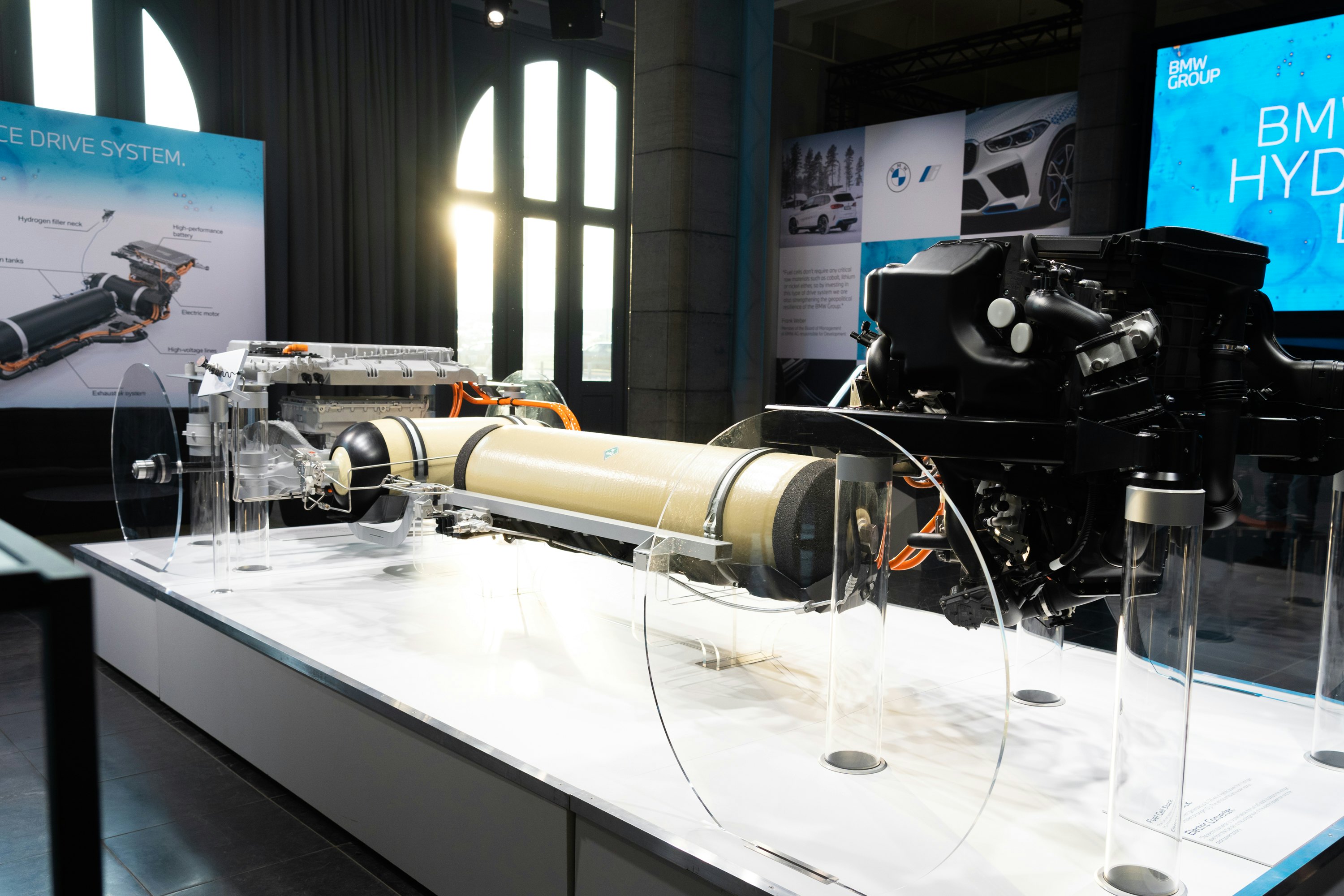

That hydrogen can then be run through a device called a fuel cell to generate power. The science is a little complex, but the gist of it is that an array of fuel cells combine the pure hydrogen with oxygen from the air. From that reaction, you get back out what you put in: electricity and water. The electricity powers the car, while the water goes back to the earth

The process is more complicated than a battery-electric car, but fuel-cell cars are still EVs — still driven by electric motors. They still have batteries, too, but tiny ones, about 95 percent smaller than that on a Tesla Model S.

That battery only serves as a bit of a buffer. The fuel cell array itself can directly provide enough electricity to drive the BMW iX5 in normal conditions. But, stomp on the throttle and it'll pull both from the battery and the fuel cell, rocketing this thing forward in the process.

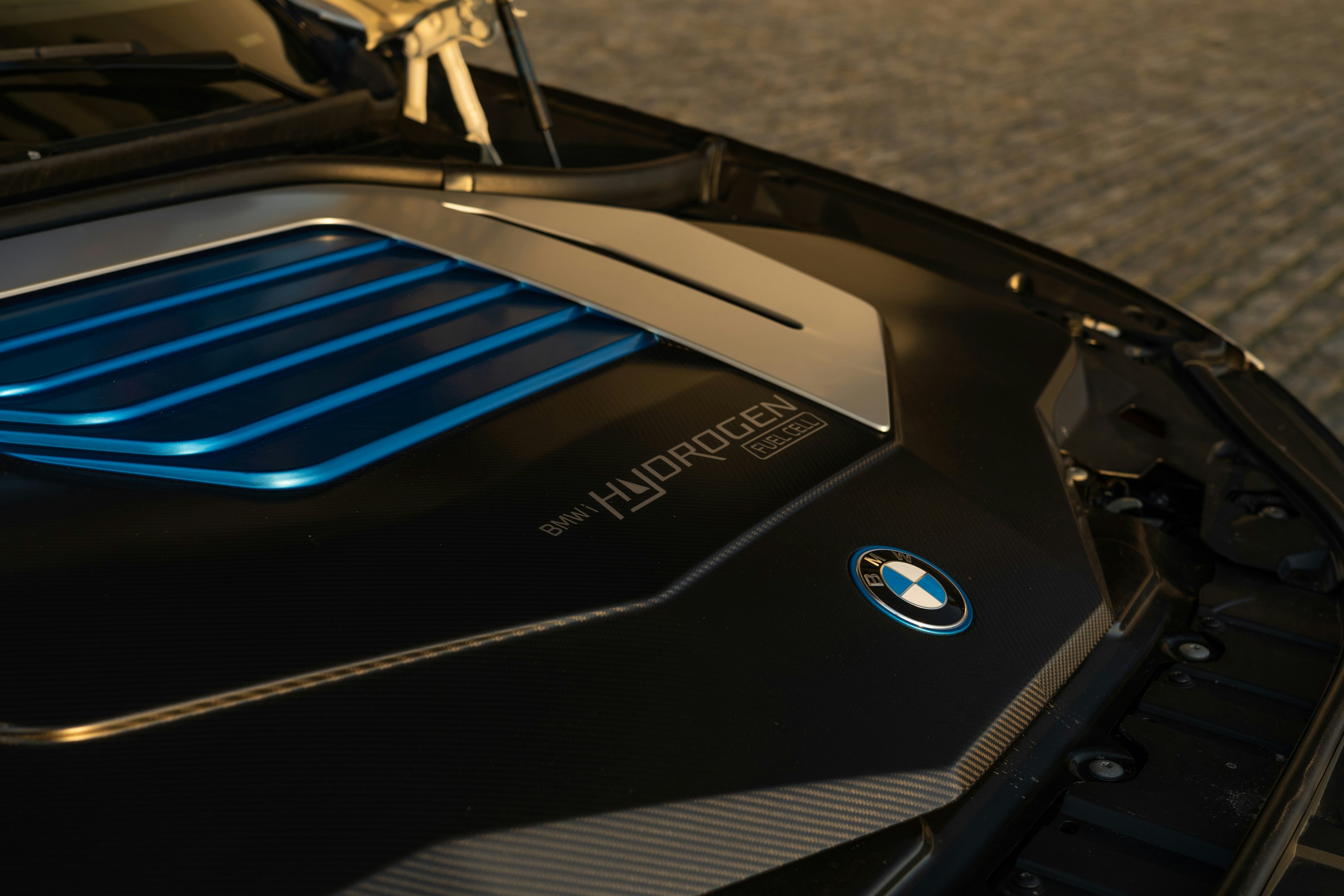

BMW has partnered with Toyota to develop the fuel cell technology, but is doing its own packaging. In the case of the BMW iX5, 383 individual fuel cells are arrayed together to provide the near-400-horsepower performance.

THE DRIVE

Driving the BMW iX5 is just like driving any other electric BMW. Pull the shifter into D, push on the right pedal, and the car glides forward silently. It's only under full-throttle acceleration that you get just the slightest bit of a whooshing sound from the fuel cell as it sucks in air and hydrogen as fast as it possibly can.

When it's doing that, the iX5 is properly quick. All 396 horsepower is available instantly, making this SUV feel like a much sportier car. In fact, it feels a lot like another quick BMW, the i4, which is where the iX5's rear-mounted electric motor is borrowed. The iX5's handling is relaxed and it's far from a corner carver — it is still an SUV — but a 0-to-60 mph time of under six seconds is better than respectable.

More important, though, is how far you can go on a charge. BMW estimates over 300 miles of range on a single tank of hydrogen, which puts it on par with big-battery luxury EVs like the Mercedes-Benz EQS. But, there's a major difference: the iX5 refuels in just a few minutes.

The process is really no more complicated than gassing up a traditional car. You just pull up to a pump, connect the pressurized line, and press a button to start. Filling a three-quarters-empty tank took three minutes and five seconds. Even the fastest of fast charging for an EV these days takes a good 15 to 20 minutes for an 80 percent charge, and about an hour to go to full. Cost? About $75 for that hydrogen, but prices are extremely elevated now thanks to energy shortages stemming from the Ukraine war. Normally, they'd be closer to half that.

The hydrogen is stored in a pair of tanks, cleverly packaged to run along the central transmission tunnel in the car and beneath the rear seats. This means that the iX5 gives up neither cargo capacity nor legroom. Those tanks are made of carbon fiber and are incredibly hard to damage in a crash. They also have safety valves to ensure that, in a situation like a vehicle fire, the hydrogen is vented safely — more of a hiss than a boom.

SUPPLY AND DEMAND

So the car is great to drive, the range is more than adequate, and the fast refueling makes it a practical solution for anybody with a long way to go. So, why aren't hydrogen fuel cell cars taking over?

It comes down to supply and demand. Specifically, the lack of supply. There are only about 70 refueling stations in the entirety of the U.S., all in California. We've seen pilot programs like the Toyota Mirai in small numbers for years, but nobody wants to invest in building more hydrogen stations elsewhere without more cars on the road. Meanwhile, nobody will buy cars without filling stations.

It's a decades-long deadlock that might finally be changing. A European Parliament proposal promises at least one hydrogen filling station within 100 kilometers everywhere by 2027. It's just a goal, there are no penalties for missing it, but it is still encouraging.

Things are happening slower in the U.S., but Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York have all signed on to an agreement to create a series of "Hydrogen Hubs" — sadly without specific timelines or goals.

Interestingly, support for hydrogen doesn't have to come at the expense of building out EV charging networks. In fact, it might be cheaper to build both, saturating urban and main travel routes with high-speed battery chargers while leaving the more rural areas to hydrogen. The most efficient way forward is not relying on ever bigger, ever heavier batteries in EVs, but instead smaller, more practical city EVs complemented with fuel-cell-powered cars for those who need to go farther or tow more.

And that's exactly what BMW's approach will be. BMW wants its entire business to be truly carbon neutral by 2050, and Dr. Juergen Guldner, general program manager of the company's hydrogen technology program, told me that hydrogen will be a big part of that: "We think in a systemic perspective, that only having one technology will not be enough to do the job."

BMW's Oliver Zipse, chairman of the board of management, said: "This is the missing link in our mobility story," saying that hydrogen not only solves many EV problems like range and recharging, but that fuel cell cars will thrive when the world's lithium supply chain hits its breaking point. "You already see that in '27 and '28, there will be a scarcity. So that is where hydrogen comes in. It uses less raw materials in a much, much smaller battery."

Looking beyond cars, this could be the beginning of a new hydrogen economy. Guldner talked about an ideal future where areas bathed in sunlight use solar cells to generate hydrogen, which will be loaded onto next-gen tankers and shipped to countries around the world, emissions-free from the air and back to it.

It sounds like an impossible dream, but Japan is already importing hydrogen from Australia, and there are plenty of other places in the world where this could happen. It's just going to take a little push to get it all started, and it finally feels like the time for that is now.

.png?w=600)