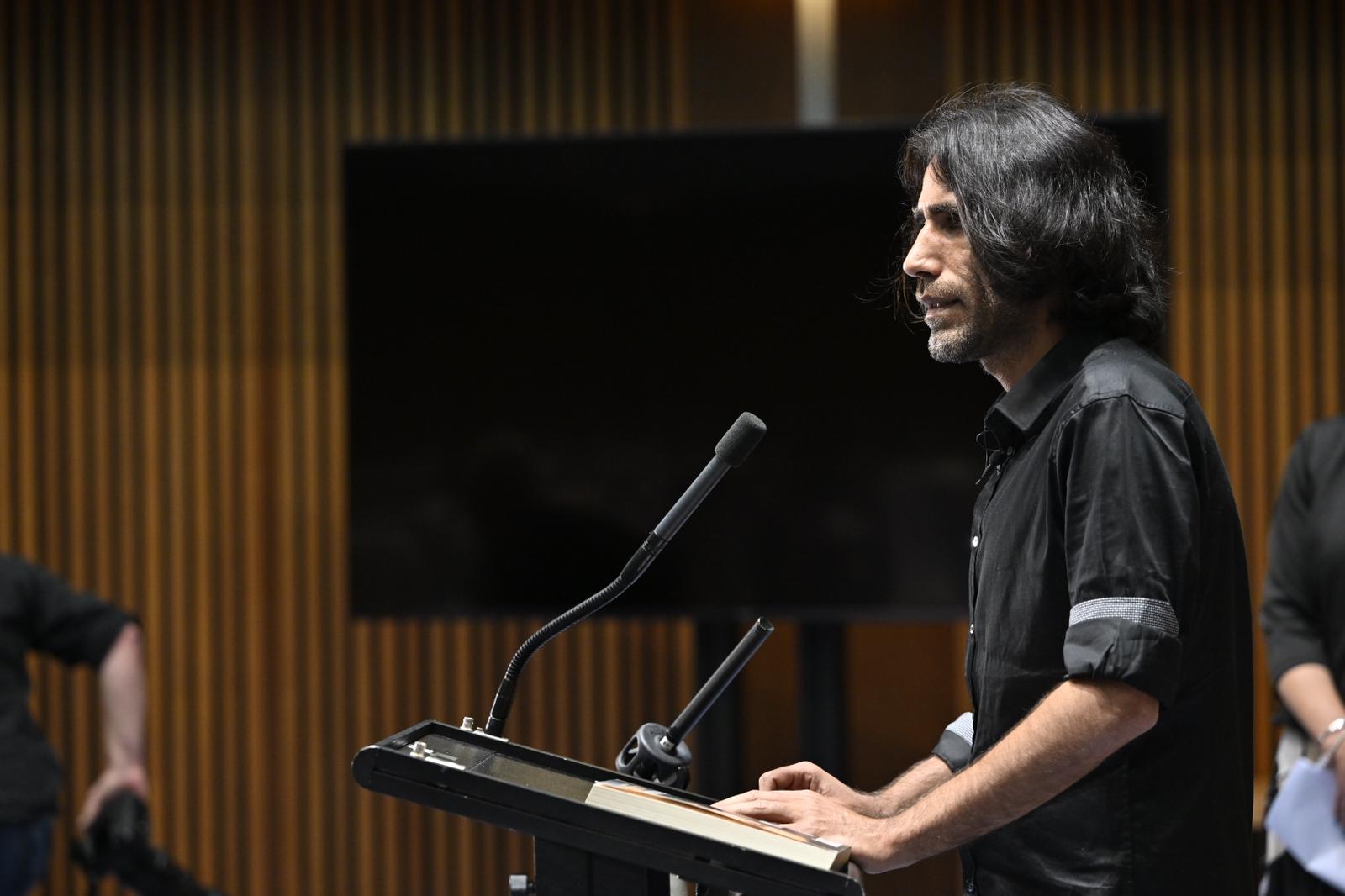

He was told he would never set foot in Australia but this week, Kurdish-Iranian author and journalist Behrouz Boochani finally entered the country’s parliament – a building where legislators’ harsh refugee policies dictated his life for six difficult years.

“It was great to be here, to be able to talk with politicians, to talk with the media and the public,” Boochani told Al Jazeera on Tuesday after his visit.

“I have been watching this particular place for years but always this place has always disappointed [refugees].”

In Australia to promote his new book Freedom, Only Freedom, the outspoken Boochani spent six years in an Australian offshore immigration detention facility on Manus Island, in Papua New Guinea, as a result of a long-term policy to send asylum seekers who arrive by boat to detention centres outside the country.

They are told they will never be allowed to settle in Australia, leaving resettlement elsewhere their only escape.

Asylum seekers spend an average of 774 days in detention, according to the Refugee Council of Australia, in conditions rights groups have variously described as “abuse, inhumane treatment and neglect”.

Canada, in comparison, holds people in immigration detention for an average of just 15 days.

It was Boochani’s determination to expose what was happening through his writing that prompted then-home affairs minister – and now opposition leader – Peter Dutton to say that he “wouldn’t be permitted to come to Australia – we’ve been very clear about that”.

Boochani’s appearance at the parliament in Canberra was in support of a proposed bill by the Greens Party to see the remaining 150 refugees evacuated from Nauru Island and Papua New Guinea and given temporary visas in Australia.

“Our work is to put pressure on this government to see real change, to see real action,” Boochani said.

Freedom, Only Freedom details the shocking treatment Boochani and hundreds of other men experienced at the hands of the Australian government while interned on Manus Island – recounting incidents of suicide, beatings, shootings, sexual violence and even murder.

Amid stifling heat and crowded, prison-like conditions, Boochani went to work as a journalist and writer.

“Nine years ago – when they banished me to Manus Island, I decided to smuggle a phone into the prison camp and start to write,” he told Al Jazeera.

“My main aim was to expose the system, expose what was happening [on Manus Island].”

Challenging stereotypes

Boochani left Ilam province in Kurdish Iran, where he was born in 1983, after he was threatened with imprisonment in 2013 because of his political activities as a Kurdish activist.

He flew to Indonesia, intending to take a boat to Australia where he planned to claim asylum, a right under international law.

It was while he was at sea that the Australian government amended laws to ensure that anyone arriving by boat – termed “irregular maritime arrivals” – would never be settled in Australia.

The boat was intercepted by Australian border security and Boochani was detained on Manus Island.

With his smuggled phone, Boochani began to contact journalists and activists in Australia and to send them his writing.

Over time, he began to be published in news media such as the United Kingdom’s Guardian newspaper, at first as a “source” but then under his name.

“I didn’t feel safe at the beginning but later, after I had created a network of journalists and human rights organisations, I felt more safe to continue to work,” Boochani told Al Jazeera.

He said his documentation of life inside Manus Island “challenged the image” of refugees as passive victims and instead gave voice to the men’s experience and resistance.

“[People] want to see refugees as a victim,” he said. “And I think being a fighter or a writer in that context was against that image. I think [the media] were not comfortable with that image. But later that changed.”

Boochani would write his first book, the multi-award-winning No Friend But the Mountains published in 2018, by sending texts written in Farsi over WhatsApp to Iranian translators based in Australia.

One of those translators was Sydney-based Iranian journalist and refugee advocate Moones Mansoubi, who coincidentally arrived in Australia as a student the same year Boochani was detained on Manus Island.

Mansoubi – who runs the Community Refugee Welcome Centre in Sydney – says she was “shocked” when she began communicating with Boochani about conditions in the detention facility.

“I came from Iran and I thought that Western countries always are faithful to international treaties,” she said.

“So for me, it was a shock, when he was explaining things in details. I couldn’t really believe how humans can treat other humans like this only because they sought asylum and asked for protection in that country.”

Boochani’s latest book, Freedom, Only Freedom, is a collection of his previous articles and writings along with essays by academics, activists and journalists who have worked with him over the years.

Iranian-Australian translator and academic Omid Tofighian says that it was a long-term strategy to elevate the writer’s work into a sphere in which he would be viewed as an equal by such scholars.

“From really early on, I started to introduce Boochani’s work to academics,” he told Al Jazeera.

“He’s an intellectual creative. He’s a writer, he’s an artist. So it was really challenging that image of refugees as weak, needy, broken victims.”

Tofighian – who left Iran as a child in 1979 during the Islamic Revolution – told Al Jazeera working on Boochani’s writings was “personal”.

“I felt my lived experience, my family history, my connection with Iran could be channelled in really fascinating, important, meaningful ways, transformative ways, into this project with him,” he said.

“And, yes, it was very traumatising. There were times when you have to really immerse yourself in the experiences that he’s talking about to really translate it well. I found myself thinking about them over many, many nights after working on it. I couldn’t sleep.”

A resident of New Zealand since 2019, Boochani’s tour of Australia has seen him speak to sold-out crowds across the country and his work held in critical acclaim.

While acknowledging his success, he told Al Jazeera he had found more satisfaction in encouraging other refugees to express their voices.

“Many refugees feel empowered, many refugees became inspired and feel they can tell their own story, they can write, they can fight,” he said.

“Not only in Manus Island, but Nauru and around the world. It doesn’t matter what you write, really, even if you write a love letter. If you write about anything that shows your dignity.”

.jpg?w=600)