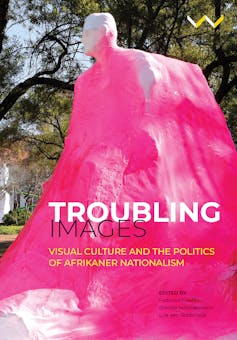

In this revised extract from the introduction to Troubling Images: Visual Culture and the Politics of Afrikaner Nationalism, the book’s editors assess how art and design helped forge Afrikaner nationalism.

In Banal Nationalism British academic Michael Billig writes, “If the future remains uncertain, we know the past history of nationalism. And that should be sufficient to encourage a habit of watchful suspicion.”

This warning has perhaps never been truer or more relevant than in the second decade of the new millennium. It has been characterised by a marked turn towards right-wing populism and nationalism.

The historical context and circumstances underlying the rise of Afrikaner nationalism belong to a different era of international politics. But it is essentially rooted in the experience of a people who were denied social and economic power. They were people whose political and cultural agency was marginalised by the imperialist agenda.

Indeed, hindsight shows that both the imperialist establishment and the international community were slow to understand the depth of Afrikaner humiliation in the aftermath of the South African War.

Consequently, they were unprepared for the meteoric rise of Afrikaner nationalism in the first three decades of the twentieth century.

Against the backdrop of resurgent nationalist sentiments across the world, it seems opportune to reassess the mechanisms through which it established and sustained itself. This is important, if only as a reminder of the need to pay attention to the risks that are posed to liberal democracy.

Theorists in the humanities have done extensive work understanding the impetuses and effects of Afrikaner nationalism and identities. But no prior book that we have encountered has been dedicated exclusively to a critical engagement with a broad range of visual manifestations and responses to Afrikaner nationalism.

Visual culture and politics

Troubling Images focuses on manifestations of Afrikaner nationalism in paintings, sculptures, monuments, cartoons, photographs, illustrations and exhibitions. In doing so it offers a much-needed critical account of the relationship between Afrikaner nationalist visual culture and Afrikaner political and cultural domination in South Africa.

Visual culture was one important mechanism for rationalising and normalising apartheid and the Afrikaner nationalist ideology that supported it. It was a domain that was multifaceted and wide-ranging. It extended from imagery accessed in private homes via print culture and television to what might be encountered in public via monuments, sculptures and art exhibitions.

Apartheid South Africa was a context in which images that challenged the status quo tended to be suppressed, and their authors threatened. It also celebrated visual discourse associated with Afrikaner nationalist ideals and values.

There were limited chances for South Africans to view state propaganda through a critical outsider lens. The country’s pariah status, as well as academic and cultural boycotts, limited opportunities for international connections.

The impact of whiteness

White South Africans who were born and reached maturity during the apartheid years tend to recognise the full impact only with hindsight. Repeated exposure to a slanted rhetoric meant that even those who sought to criticise nationalistic views were influenced by its biases.

In an article titled How do I Live in This Strange Place? published some 16 years ago, Samantha Vice called for shame and a retreat from public life as the appropriate response by white South Africans to the horrific racial injustices perpetrated in their interests.

Though controversial, her position highlights the fact that a decade after apartheid ended people were still coming to terms with the long-term impact of its rule.

For white South Africans, this involved critically engaging with questions about their own culpability. The growth in critical whiteness studies in the new millennium is surely also tied to a need to interrogate debates in South Africa prior to 1994. And that includes its visual ones.

It stands to reason that the current retrieval of a positive blackness from decades of systematically imposed inferiority should be accompanied by a critical reconsideration of whiteness and its strategies of domination and control.

The living monuments

Images celebrating Afrikaner nationalist imagery remain visible – and sometimes even prominent – in South Africa. The public domain still includes numerous sculptural commemorations of key figures within a white Afrikaner imaginary.

South Africa retains architectural monuments of significant scale. There’s the Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria, the Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein and the Language Monument in Paarl. Their retention can be understood in light of the National Heritage Resources Act (1999). It sought “to enable and encourage communities to nurture and conserve their legacy so that it may be bequeathed to future generations”.

But the appropriateness of this approach has increasingly been questioned. Since the removal of Marion Walgate’s sculpture of Cecil John Rhodes from the University of Cape Town, many of South Africa’s monuments have suffered some form of desecration.

In such a context, the discussion of Afrikaner nationalism and visual imagery undertaken in this book seems timely.

Brenda Schmahmann's SARChI chair in South African Art and Visual Culture at the University of Johannesburg is funded by the Department of Science and Innovation and managed by the National Research Foundation. Please note, however, that the.opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed here are those of the three authors of the introduction to the volume, and the NRF accepts no liability in this regard.

Federico Freschi receives funding from the National Research Foundation of South Africa

Lize van Robbroeck does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.