A few weeks ago, my parents woke up to find a large, orange swastika daubed in paint on a wooden plank outside their house in Sydney. We have a mezuzah attached to our front doorpost, so the “dauber” knew we were a Jewish household. At the time, my parents were angry and sad more than frightened.

My family’s experience cannot compare with the hate that burst forth in Pittsburgh several weeks ago, when 11 congregants at the Tree of Life Synagogue were murdered simply because they were Jewish people attending prayer. But we are living in a period of increasing hatred directed at minorities of all kinds, and anti-Semitism is on the rise across the globe.

The Pittsburgh synagogue gunman, Robert Bowers, raged in online platforms that Jews were “invaders” trying to destabilise the United States. They were, he said, “an infestation” and “evil”. Bowers’ rants cast Jews in the role of dangerous revolutionaries out to destroy Western civilisation. This has long been a staple perspective of anti-Semitism.

In my research, I have been studying the anti-Semitic images that were commonplace in Vienna early last century. These stereotyped images served to vilify Jewish people, culminating in the removal of most of the Jews from Vienna in 1938.

I believe it is important that we reflect on these upsetting images to consider how the “mainstreaming” of anti-Semitic ideas and images in popular media can have terrible consequences.

Caricatures in the fin-de-siècle Viennese press

At the turn of the century, the Austrian capital was home to the third-largest Jewish population in Europe after Warsaw and Budapest. Accounting for almost 9% of Vienna’s population, Jews were a highly visible minority. They were also a constant source of conversation and fear within Vienna’s political and civic arenas.

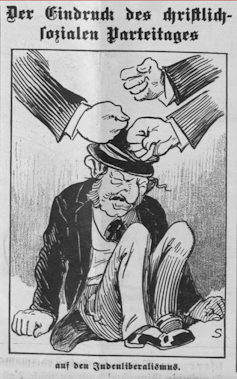

Anti-Semitic caricatures and literary sketches in the Viennese press ran rife from the end of the 19th century until the German annexation of Austria in March 1938.

The cartoons presented a variety of messages that characterised Jews in a number of negative roles: as the binary opposite to Aryan morality and virtuousness, as money-grubbing parvenus, or as attempting to take over large parts of the city. What all these stereotypes had in common was their characterisation of Jewish people as an Other who did not belong within European society.

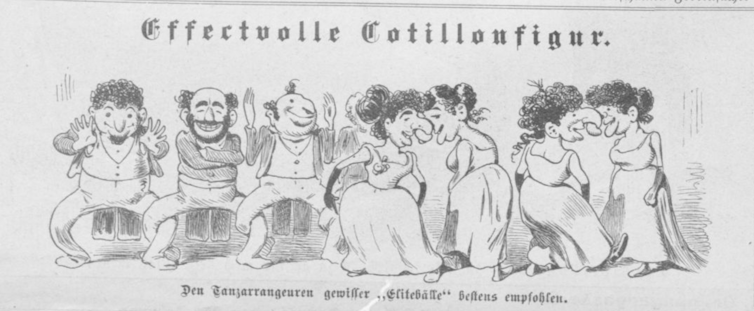

One caricature from the widely read Viennese biweekly satirical magazine Kikeriki, published in 1900, comments on the presence of Jews at elite social events.

It depicts Jewish men and women ridiculed for their supposed racial characteristics (a view strongly influenced by the popularity of eugenics and Social Darwinism during this period) and, by satirising the popular dance styles at elite city balls, implies that Jews dominated Viennese elite circles. The image’s caption makes no overt references to Jews, but the visual stereotypes would have made it very clear to the readers what this image was about.

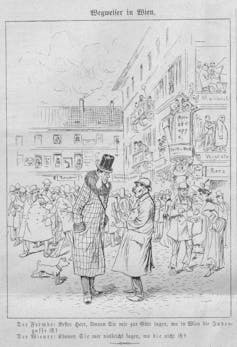

Another cartoon from 1890 in Figaro (not to be confused with the popular French daily Le Figaro) depicts two men meeting on a crowded Viennese street. One of the men, a visitor, asks a local if he would be so kind as to point out the Judengasse [Jews’ Street]. The latter replies, “Perhaps you can tell me where is it not.”

The scene behind these two gentlemen is filled with characters drawn with common Jewish bodily stereotypes: large hooked noses, dark curly hair and thick lips.

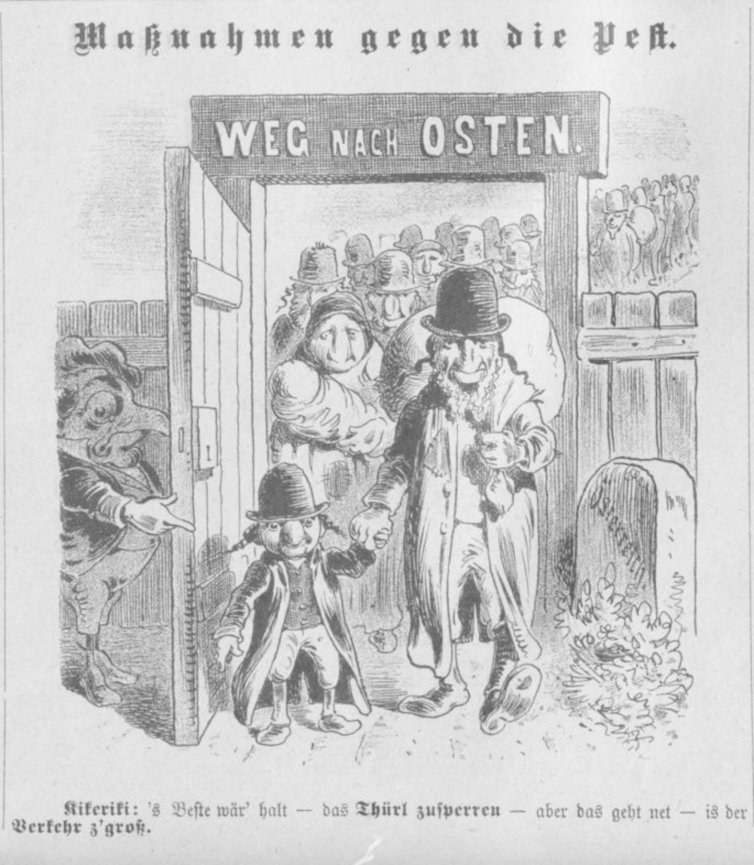

Although at this time most Jews living in Vienna spoke German and were adherents to secular German culture, the figure of the Ostjude (Eastern Jew) was a typical feature of these cartoons. Anti-Semitic cartoonists, newspaper editors and politicians harnessed a fear connected to an increased Jewish migration from Austria’s eastern crownlands and the pogroms of the Russian Empire.

Despite the fact that Yiddish-speaking, Orthodox, traditionally attired Jews never accounted for the majority of Vienna’s Jewish population, cartoons often depicted them as descending en masse into an unsuspecting “German” city.

Other cartoons bemoaning Vienna’s “Jewification” gave way to those speculating on the revenge that would be meted out to the Jews; not necessarily violence and murder, but other forms such as banishment from the city and its social and political arenas.

‘Jewification’ and revenge today

The effects of this tradition of anti-Semitic representation are clear. It took very little for average men and women to turn on their Jewish neighbours and colleagues after the German Anschluss in March 1938.

Many Viennese Jews were lucky to escape. Some, just under 2,000, found a haven in Australia. They have since, like many other refugees and migrants, contributed to the economic, cultural and political development of Australian culture in the post-WWII period.

Yet the themes of “Jewification” and revenge expressed in these cartoons are, sadly, still relevant today.

In his online rants, for instance, Bowers had condemned the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) – a Jewish refugee advocacy and support group founded in New York in 1881 – for “bringing in invaders”.

The Hungarian-born Jewish billionaire philanthropist George Soros, meanwhile, has been the target of anti-Semitic demonisation. And in Charlottesville last year, hundreds of mostly young white men marched with torches chanting the Nazi slogan “Blood and Soil” and “Jews will not replace us”.

How we speak about and depict others in the media and social discourse perpetuates long-held stereotypes and ultimately emboldens hate-filled individuals. It is for this reason that we should look to the past – and learn from it.

Jonathan C. Kaplan's research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.