The entrance is marked by an AI-generated image of a dead whale, floating among wind turbines. On the first floor of the East Maitland bowling club, dire warnings are being shared about how offshore wind may impact the Hunter region – alongside a feeling of not being consulted, of being steamrolled.

“Environment and energy forums” like this one in late November have been held up and down the east of Australia, aiming to build a resistance to the country’s renewable energy transition.

Today’s event is being cohosted by No Offshore Turbines Port Stephens (NOTPS) and the National Rational Energy Network (NREN), a group with informal National party links that was behind February’s Reckless Renewables rally in Canberra. The advocacy group Nuclear for Australia is also here.

“We’re not a political group,” the NOTPS secretary and a Port Stephens resident, Leonie Hamilton, tells Guardian Australia.

“We’re not there to push [politicians] into parliament, but we are going to listen to what they have to say.”

Hamilton says she’s undecided on the issue of nuclear power.

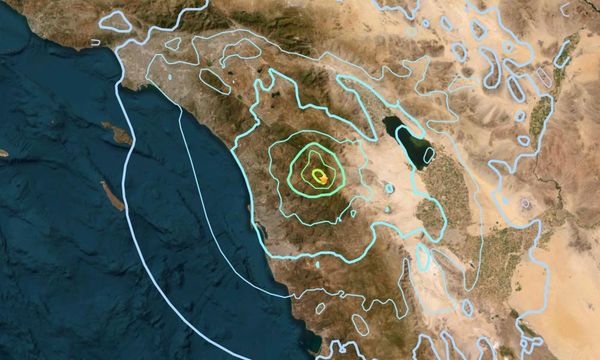

The coastline of the Hunter was declared a potential area for offshore wind in mid-2023 after “extensive community consultation”, according to the federal government. But some, such as NOTPS’ Ben Abbott, are still angry about a perceived lack of detail about the project.

Today’s forum is about raising awareness across the Hunter, Hamilton says. “We think it’s important it happens before the election, so that people understand what the costs are.

“[The coast] belongs to everyone and they should have the opportunity to understand what’s going on.”

There are local groups like NOTPS around Australia that want their broad concerns about the rollout of renewable energy to be heard but say they do not want to be used for a political agenda and do not advocate for particular energy sources.

But working alongside those groups is an increasingly coordinated alliance of conservative thinktanks, political lobby groups and politicians who are flatly opposed to the clean energy transition.

Fears about the environmental and social impact of renewables projects are finding purchase in an information gap critics say has been ceded by the government, the industry and environmental groups – and there are plenty of interested parties willing to step in.

An earlier NREN event in Sydney was sponsored by the Institute of Public Affairs.

Sandra Bourke, a cohost of the Maitland event, is an NREN member but also a spokesperson for the conservative lobby group Advance – which was a key player in the defeat of the Indigenous voice to parliament and is now fundraising on a “lies of renewables” campaign.

A Facebook account under Bourke’s name is present in almost 20 community Facebook groups and pages opposing renewable projects, from Kilkivan, Queensland, to Bunbury, Western Australia, regularly sharing Advance clips and links to Sky News.

The upcoming election is a “crossroads”, she tells the crowd, while declining an interview with Guardian Australia. There’s an Advance sign-up form on every seat.

Up the back of the room are “Where’s Meryl?” posters, referring to the Labor incumbent MP Meryl Swanson, who holds the local electorate of Paterson.

The Liberal candidate Laurence Antcliff is here, along with three men in T-shirts bearing his name. He tells the room he is opposed to the offshore wind project in Port Stephens and will “fight every single day” to ensure it does not go ahead.

Swanson, who has said “many, many meetings” were held with local groups about the proposal, was not invited.

The nuclear energy wedge

In June the Coalition announced it would lift the bans on nuclear energy if it won next year’s election, then build nine publicly owned reactors at sites around the country.

The announcement gave extra fodder to advocacy groups and conservative thinktanks that have long opposed the shift to renewables.

Last week the opposition leader, Peter Dutton, appeared in Port Stephens alongside Antcliff. “It’s in this community’s best interest that [the windfarm] project does not proceed,” he said, as he spruiked the alternative of nuclear power.

Facebook groups opposing renewables projects are now increasingly full of pro-nuclear content, and groups such as Nuclear for Australia have set up dedicated social media accounts targeting specific sections of the community – such as an Instagram account titled “Mums for Nuclear” – as they gear up for the election campaign.

A new report looking at the pro-nuclear information ecosystem, funded by the progressive campaign group GetUp, found a “likely-coordinated and sophisticated ecosystem” of thinktanks, not-for-profits and political operatives engaged in pro-nuclear messaging.

For these interests, the focus on nuclear energy is a chance to “present a solutions-based response to climate change, and divert attention from their pro-coal and gas positions”, the report concluded.

“Nuclear energy provides a wedge for the environmental movement, climate independents, the Labor party and Greens, because it stokes division and can bog them down in technical explanations of why nuclear is neither desirable nor viable in Australia.”

Ed Coper, who is the chief executive of the communications agency Populares and has worked on teal campaigns, says the volume of noisy opposition to renewables is disproportionate to community attitudes. Nevertheless, he predicts nuclear will be an effective election campaign wedge.

For parties opposed to the clean energy transition, this is an opportunity to “peel off” environmental support from renewables support. The message to this cohort is broadly that “renewable energy generation is ruining pristine farming land and is not a good use of land and destroys the habitats of protected species and pristine views”, he says.

“That gives [the Coalition] a whole new constituency. If Labor goes into the election assuming everyone is against nuclear energy, they’ll be in for a shock.

“Energy transition requires an enormous amount of social licence.”

Solar plans discovered by chance

About 200km north-east of Melbourne, John Conroy and his family have been producing beef in Bobinawarrah since the 1960s. In a neighbouring paddock are plans for the large Meadow Creek solar farm and battery – plans he discovered by chance in September 2022 after a visit from the electricity distribution company AusNet.

“We alerted the community,” he says. “The project had been in the process for 12 months before we even knew about it.”

He says the main concerns of the community surround fire risk – both from the project but also the liability of landholders if fires on their properties spread to the solar farm.

In April the Victorian government removed the rights of landholders to appeal against planning decisions made on renewables projects.

“That is a real slap in the face,” Conroy says. “We’re a community of working-class people, producing food, doing our best to keep footy clubs going, and then the government takes away your rights to have a say.”

The independent federal MP for Indi, Helen Haines, says questions about insurance liability “should have been answered long ago”.

“We should be having these conversations long before a project is up for a planning permit.”

Families like the Conroys in her electorate are spending hundreds of hours getting across technical details of projects and government rules. “It shouldn’t be that way,” she says.

Haines says communities are operating in a “vacuum” and she wants to see information hubs in regional centres where people can go for trusted information and support.

The MP, with Senator David Pocock, last year successfully pushed for a government review into the way communities were being asked to host major renewables projects.

More than 700 people attended 75 meetings, with the review making nine recommendations the government said it would implement in collaboration with the states.

Governments needed to allow only reputable developers to build projects, the review said, and zones should be identified to avoid projects targeting inappropriate land areas.

“There is pushback – this is real and the concerns that communities have are existential,” Haines says. “We have to stop trying to generate social licence after a decision has been made.”

Instead, she says, the transformation should be about regional development and making sure communities have genuine long-term benefits from any projects.

“I want to look back and see better roads, better healthcare and internet, better childcare services, and see that the renewable energy transformation helped us get there. But communities are just not seeing that.”

Locals want ‘some control and influence’

“The fundamental issue here is there’s an assumption that there is no time to properly talk to people and give them not just a tokenistic say, but give them some control and influence in managing their local environment,” says Georgina Woods, who has 25 years of climate change activism and advocacy behind her.

Woods is head of research and investigations at the campaign group Lock the Gate, an organisation that emerged from the unrest among farmers and landholders at the coal seam gas boom in Queensland in the 2000s.

Governments have failed to clearly articulate why the transformation is needed and the urgency of climate action, she says. “We are getting further away from a broad consensus on why these projects are being done in the first place.”

“Until we put people and landscapes and nature at the centre, we’re at risk of repeating the same mistakes with renewable energy that we made with mining.”

West of the Blue Mountains in New South Wales are the gently rolling hills of Oberon. Outside town are plans for a 250-turbine windfarm on pine plantations owned by the state government.

Chris Muldoon, a committee member of Oberon Against Wind Towers, says that would mean local landholders would miss out on any financial benefits of hosting turbines while the town would have to live with the sight of turbines almost 300 metres tall in an area known for its postcard aesthetic.

“They’re chasing the wind and the towers, but there’s no consideration of the economic or social impact,” says Muldoon, who manages Mayfield Garden in Oberon, a tourist attraction owned by the wealthy Sydney-based businessman Garrick Hawkins.

Hawkins has contributed to the campaign to block the windfarm, says Muldoon, as have many locals.

In September the group put up nine candidates for the Oberon council elections, with two elected. Their pitch was uncompromising. “Oberon First are the only candidates who have committed to slamming the door in the face of greedy, arrogant wind tower developers,” the group said.

Oberon has a lot of hobby farmers and second homes for people in Sydney, says Muldoon, which means they have “city skills” that have mobilised against the development, something other communities do not have.

The group is not against windfarms or renewable energy, insists Muldoon, but “you just need to make less invasive decisions about the rollout”.

He points to people living in renewable energy zones, where surveys have shown broad support among farmers for renewables projects.

Outside those areas, he says, projects often come as a surprise to communities that are ill-prepared to navigate the technicalities of dealing with planning regulations, or wading through environmental impact statements “that can be 1,000 pages long”.

“Outside the renewable energy zones, the framework isn’t working,” he says. “It’s the wild west.”

Oberon is in the federal electorate of Calare, where the independent Kate Hook is trying to unseat Andrew Gee, who quit the Nationals to sit on the crossbench in 2022 over the party’s opposition to an Indigenous voice to parliament.

Hook left her job in September working for a not-for-profit to help communities negotiate with governments and renewable energy companies to get the most benefit from projects.

She says the “missing piece” causing communities to push back is a lack of understanding of why the transition away from fossil fuels is needed and how it could benefit them.

“People shouldn’t have to rely on Google, but this is why people are anxious,” she says. “There’s a tsunami of misinformation.”

“People might not like the look of windfarms, but do they want farmers to be able to stay on their land? Because these projects can help them do that.

“What we need is discussion, not division.”

A spokesperson for the climate change and energy minister, Chris Bowen, said the government was “working with local communities to secure regional jobs and provide energy security”.

“Unfortunately, the former Coalition government spent 10 years failing to make the necessary reforms to improve community engagement in a rapidly changing energy market,” she said.

The government was implementing the community engagement review “to enhance community support and ensure that electricity transmission and renewable energy developments deliver for communities, landholders and traditional owners”.