400,000 years ago, early humans in Europe, Asia and Africa lived alongside giant straight-tusked elephants, far bigger than their modern-day cousins. Their evolution has long been a mystery to palaeontologists, but an extraordinary, enormous and near-complete skull is helping us uncover an obscure episode in the evolutionary history of these prehistoric megaherbivores.

This remarkable specimen was excavated, alongside 87 prehistoric stone tools, in northern India’s Kashmir Valley in late 2000 by team of geologists that included Drs. AM Dar and MS Lone of Government Degree College in Sopore, Dr. Ghulam Bhat of Jammu University, and veterinarian Dr. MS Shalla.

Though fascinating, the find raised more questions than it answered: What kind of elephant died there? And did this giant meet its end at the hands of early humans?

Fast forward to 2019, while I was studying for my PhD on the fossil history of elephants, I got exciting news from my colleague Advait Jukar that he would be joining an international scientific team assembled by Dr. Bhat to further investigate the remains from Kashmir.

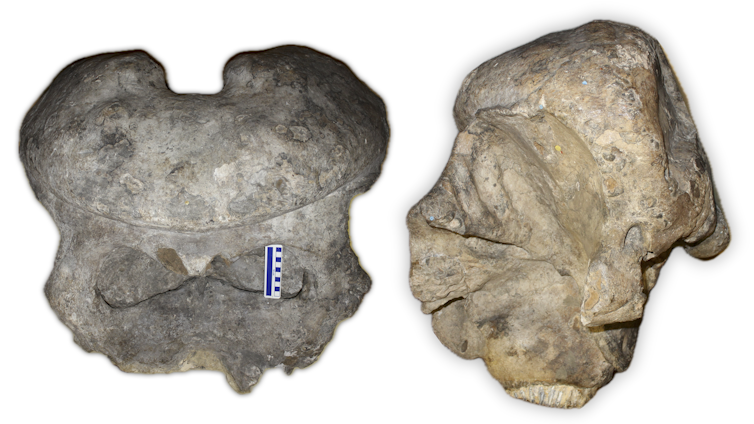

The findings were truly astonishing. It was the most complete fossil elephant skull from India that the researchers had ever seen, and it was massive: 1.37 m tall from the skull roof down to the base of the tusk sheaths, indicative of of an immense herbivore standing 4 metres tall and weighing around 13 tonnes.

Painstaking precautionary work was needed to conserve the skeleton before Advait could study it. The skull was placed on a plaster base in a wood and glass display case, which he had to crawl into to work on the skull!

Our other colleagues from the British Museum, the London Natural History Museum, the University of York, and Jammu University worked to stabilise the rest of the skeleton. They also inspected the bones for signs of human exploitation, examined the 87 stone tools that were found scattered around the skeleton, and sampled enamel from the teeth to ascertain an approximate age for the site.

The site itself is also unique, as it is the only one over 10,000 years old in India that preserves a skeleton with noticeable signs of human butchering. Together with the stone tools, this makes it the oldest unambiguous site documenting prehistoric human activity in the Indian subcontinent. The stone tools were likely made by a species of human different from us, and the whole site probably dates to around 300,000-400,000 years ago, a time known as the Middle Pleistocene.

Who these mysterious humans were, we don’t know – they might be linked to Neanderthals, or perhaps to the more enigmatic Denisovans. Humans aside, however, the skull’s shape presented a conundrum, one that led us to embark on an palaeontological detective story.

Leer más: Their DNA survives in diverse populations across the world – but who were the Denisovans?

“A caricature of an elephant’s head”

Prior to the project getting underway in 2019, we were already aware of the Kashmir elephant skull through webpages and books. Photographs of the excavation showed that the skull belonged to the extinct genus Palaeoloxodon, commonly known as ‘straight-tusked elephants’.

Intriguingly, the Kashmir Palaeoloxodon lacks the prominent, headband-like bony crest jutting above the forehead from the skull roof seen in the classic Indian Palaeoloxodon, known as Palaeoloxodon namadicus.

The Victorian-era Scottish naturalist Hugh Falconer described the first Palaeoloxodon skull ever found in central India’s Narmada Valley back in 1845, which gave P. namadicus its name. Noting the distinctive skull crest of P. namadicus, Falconer remarked that it was “so grotesquely constructed that it looks the caricature of an elephant’s head in a periwig”.

Giant elephants in Europe

Since the 1930s, it was generally thought that a less exaggerated skull roof crest separates the European species, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, from the Indian species first noted by Falconer. However, this interpretation has been challenged a number of times by the discovery of Palaeoloxodon skulls with namadicus-like heavy set skull crests in Italy.

This brought about two competing hypotheses. Either the skull crest is variable in European populations, potentially related to sexual maturity or dimorphism, or there was once a single species ranging throughout the Eurasian mainland (which then included some modern-day island landmasses such as Britain and Taiwan).

Working with Italian and Spanish palaeontologists, I was part of a team of that resolved this confusion in 2020. By extensively comparing skulls from Europe and central India, my team concluded that in all Palaeoloxodon, the crest becomes more thickened and forward-projected with maturity, but in mature Indian specimens the crest becomes even more heavy-set than on similar skulls found in Germany and Italy.

In other words, this means P. antiquus and P. namadicus were two distinguishable species inhabiting different regions.

However, a Palaeoloxodon skull discovered in Turkmenistan breaks this mould. The Turkmen elephant was fully mature – as indicated by two brick-sized wisdom teeth taking up both tooth rows on the upper jaw – but its skull bears a wide, flat forehead that lacks a crest. In 1955, the late Russian palaeontologist Irina Dubrovo concluded that this skull represented a new, distinct species, which she named Palaeoloxodon turkmenicus.

As the aforementioned pattern began to emerge from the research on European and Indian skulls that my team had published in 2020, we began to wonder if Dubrovo’s supposition was valid after all.

Deciphering the mystery of the Kashmir skull

For all these reasons, we were excited to receive the news in 2019 that Advait would be joining Dr. Bhat’s research team to undertake a detailed first-hand study of the fabled Kashmir Palaeoloxodon skull, which we already suspected to belong to the same species as the Turkmen skull. Upon initial communications from Advait, we tentatively suggested in our 2020 study that the Turkmen and Kashmir skulls represent a distinct species.

Advait then invited me to help solve the mystery of the aberrant Kashmir skull. It took months for us to assemble and scrutinise all relevant information – taken from both our own observations of various specimens and from scientific literature – but it helped us draw a number of conclusions.

The general shape of the Kashmir skull, particularly the forehead, is most similar to the Japanese species P. naumanni, which evolved around the same time. P. naumanni is also characterised by an underdeveloped skull crest in fully mature individuals, in marked contrast to P. antiquus and P. namadicus. However, the Turkmenistan and Kashmir skulls had crests that were even less pronounced than in P. naumanni, suggesting they were a different species.

A further standout feature of the Kashmir skull is the rare preservation of stylohyoids, part of the elephant’s intricate tongue-bone (hyoid) apparatus that controls the tongue and throat during feeding, vocalisation and water intake using its trunk. The stylohyoids from Kashmir differ from both Japanese P. naumanni and European P. antiquus. Moreover, we identified nothing to suggest that the Turkmeninstan and Kashmir skulls were from different species.

Thus, we had grounds to conclude that the Kashmir Palaeoloxodon is an important additional specimen of P. turkmenicus, which had a distribution stretching from Central Asia down to the intermontane basin south of the Himalayas.

An evolutionary bridge

Palaeoloxodon first evolved in Africa between 1.5 and 1 million years ago, before subsequently spreading across vast parts of Eurasia. Our research found that P. turkmenicus and P. naumanni represent an evolutionary ‘go-between’ that links the skull structure of the founding African species to Eurasian forms with their elaborate skull crests.

What remains uncertain is whether P. turkmenicus was indeed the archetype that gave rise to other Eurasian species with more pronounced skull crests, or whether it represented an abrupt early offshoot in the evolutionary story of these magnificent Pleistocene giants.

Steven Zhang received support from the Geological Society of London, Jeremy Willson Charitable Trust, the Palaeontological Association, and the Natural History Museum (London) upon completing the research discussed in this article. He has no further relevant affiliations to disclose beyond his current academic employment.

Advait M. Jukar received funding from the British Museum, the Deep Time Peter Buck Fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution, and Gaylord Donnelley Postdoctoral Fellowship through the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies while conducting this research. He has no further relevant affiliations to disclose beyond his current academic employment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.