When I woke up on the morning of February 24 to the news that Russia was invading Ukraine, my first thought was about my brother. He had been in Lviv, in Western Ukraine, on a business trip.

In our family group chat, my sister-in-law told us from their home in Serbia that my brother was still in Lviv that morning. He was evacuating overland, through Poland.

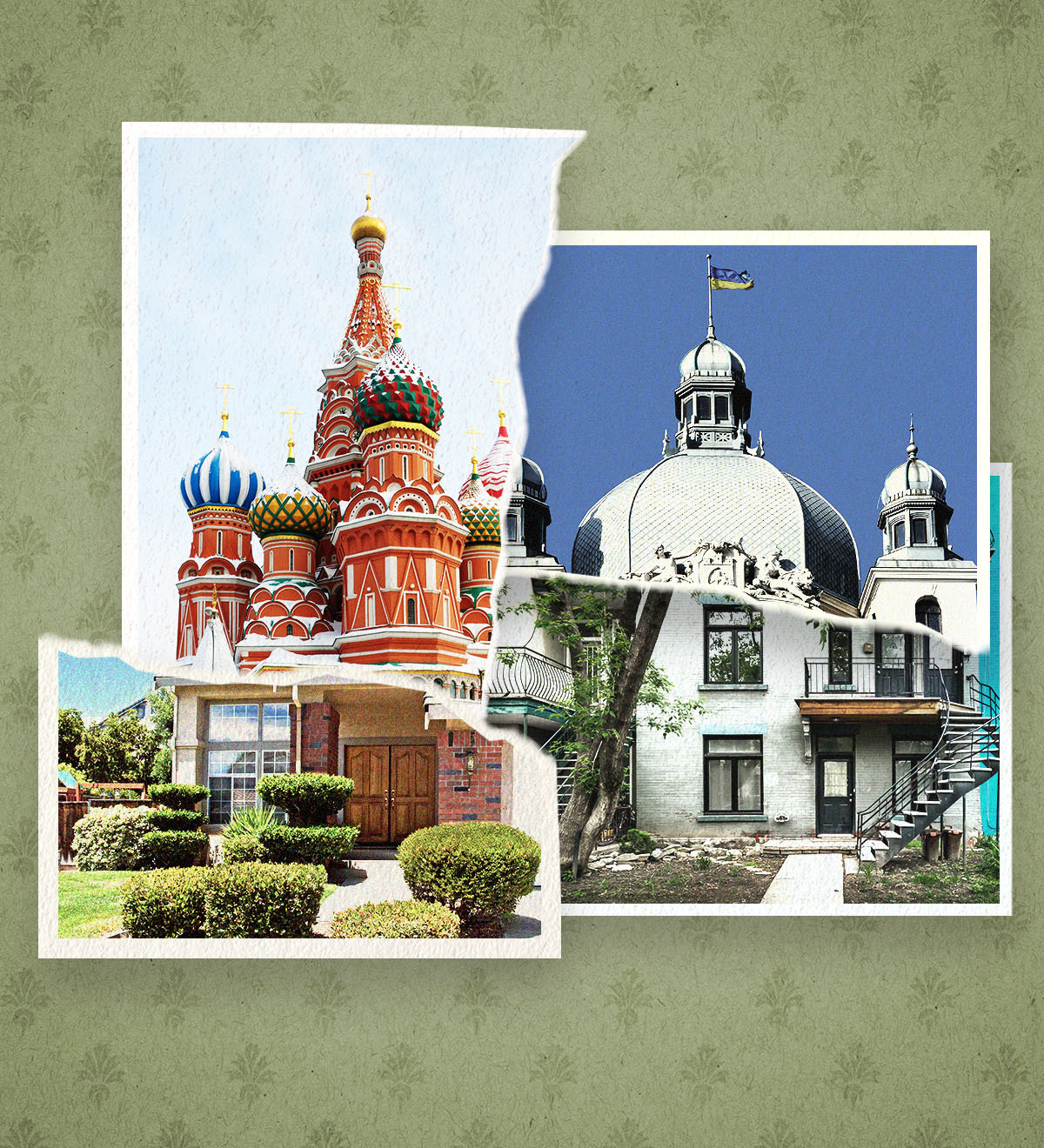

Almost eighty years ago, my father, Dimitry Pospielovsky, had made a similar journey. As a nine-year-old boy in 1944, he had fled a region of what is now Western Ukraine ahead of the Soviet Red Army’s offensive. For my family, like for so many others with Ukrainian origins, the relationship between ethnicity, language, and land is messy, confounding definitions and nationalities. Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, or Jewish . . . we share a history of conflict, oppression, and hope.

Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine rips at these bonds, stoking internecine conflict, and perhaps extinguishing any promise of liberal democracy in Russia, the fight for which has shaped my family for four generations.

My grandmother, Marianna Ushinsky, fled Russia with her family during the 1917 revolution.

The Ushinsky family estate was near a town now known as Rivne in Western Ukraine, east of Lviv. Part of Russia before the First World War, Western Ukraine was in Poland between the wars. In the 1920s, my grandmother travelled there to sell off the Ushinsky estate lands. She married a Russian doctor and had four children (one died as a child). They separated soon after my father was born.

When the Soviets occupied Western Ukraine in 1939, after the Nazis invaded Poland, my grandmother had wanted to flee again. My mother, who knows this story well, tells me that my grandmother was aware of the horrors of mass purges and the man-made famine that was wiping out millions across the border with the Soviet Union. Her family had held senior posts in the Tsarist civil service; she’d gone to school in England—she would be a target.

But, my mother says, the villagers, whose families once worked on the Ushinsky estate and worshipped in the family church, convinced my grandmother to stay, promising they’d protect her. So, she hunkered down, burning her foreign-language books and magazines and burying incriminating documents, according to the memoir my father wrote about his parents’ lives.

Sure enough, my mother says, within a day of the Soviets’ arrival, an intelligence commander was at my grandmother’s house to question and search. He spotted the photo of her grandfather hanging on the wall. Konstantin Dmitrievitch Ushinsky had been a revered educational reformer, celebrated in both Ukraine and Russia, with schools and colleges bearing his name. According to my mother, my grandmother told the officer that the man was her grandfather. “You have nothing to fear. You are under my personal protection,” she remembers him saying before he left.

Two years later, the town was occupied by German forces. Most of the population was Jewish, and tens of thousands were slaughtered. According to my mother, my grandfather kept secret his own Jewish heritage that would have marked his family for extermination. My father learned of his own heritage only after the war.

When the German armies retreated, my family, like millions of others, fled as Stalin decreed that suspected traitors be deported. After the war, as per the Yalta agreements, millions of refugees were forced to return to the Soviet Union from refugee camps to face deadly exile and gulags.

My grandfather remained in Poland with his new wife, dying in 1964 without ever seeing his children again, but my grandmother and the children eventually emigrated to Canada in the 1940s. She lived until 1989 but, afflicted with dementia, she was robbed of a chance to witness the decline and eventual fall of the regime that had chased her family and killed her father and a brother.

Before her death, she was staying with my family in London, Ontario. In her room, I found a little box for playing cards—she was a habitual solitaire player. Inside, carefully wrapped in a handkerchief, was a bundle of desiccated dirt that crumbled to sand in my fingers.

My father had his own journey of return: in the late 1950s, about a decade after coming to Canada and graduating from university, he went back to Europe, ostensibly to free Russia from communism. When stuffing leaflets in the hands of Soviet merchant sailors in Hamburg failed to overthrow Stalin’s regime, he shifted his battleground to England. He then enrolled in graduate school and met my mother (my Serbian mother learned to speak Russian, and my father learned to speak Serbian).

In 1964, translating for the British trade exhibition in Moscow, my Russian father actually set foot in Russia for the first time. My siblings, growing up in London in the ’60s, were baby-sat by defectors.

My father’s pursuit of the fight for democracy relocated my family internationally three times in six years. In 1967, he got his first academic job at the Hoover Institution at Stanford in California (where I was born in 1969), a renowned incubator for conservative foreign policy; then finally—at my mother’s insistence—he got a job in the country of his passport, at Radio Liberty in Munich; and then the family moved to London, Ontario, when he became a history professor at the University of Western Ontario in 1972.

Russian was our language at home. Our home life was defined by that struggle against the communist oppressors who had forced my father’s family from Ukraine. Far removed from the front lines of the Cold War though we now were, the fight continued on our dining-room table: we hand-addressed (better to slip past the censors) pamphlets for the USSR; we assembled the indexes for my father’s books, and we hosted and toasted countless scholars, dissidents, and exiles.

In 1986, we were back in Europe. We drove to Berlin, where we gawped with all the other tourists at the Wall. Gazing over the barrier at the no-man’s-land of combed sand, trip lines, and guard towers, it was impossible to imagine that in just a couple of years, my father would not only be able to go to the USSR and visit the place of his birth but teach and write there too. Let alone that, his Ukrainian homeland would soon be an independent country.

In the ’90s, a Canadian recession pushed me to eastern Europe. I went to Moscow to study theatre. My parents had just purchased an apartment there, and my father had already built up a network of contacts during the glasnost years. I abandoned theatre studies for freelance writing and later taught English in Moscow, first in 1992 and again from 1994 to ’96, this time with a Canadian wife.

Right after the fall of the Soviet Union, Moscow felt like a boiling cauldron of change. Pushy, visceral, exciting, ridiculous, and so much fun. Russians of my parents’ age were exhausted and constantly apologizing. But I was always ready, waiting for the next bit of progress: this project is going ahead, that article published, this law enacted . . . Eventually, normal life caught up with me, and we returned to Canada in 1997.

When Putin emerged from obscurity in the late ’90s as Boris Yeltsin’s hand-picked successor, his dullness was refreshing, or at least no worse than what had come before. Practical and pragmatic, he seemed to embody that striving for what I thought of as “normal.”

By the 2000s, my father had mostly retired from teaching at Western and was spending half his time teaching and writing in Russia. One night, in Canada, my mother got a call from him soon after he’d arrived in Moscow. “I don’t know why I’m here. I don’t know where I am,” he said. At the time, she thought it was a vocational cri de coeur, a spiritual crisis in the face of Putin’s creeping U-turn from a liberal-democratic promise. Was my father questioning the mission that had driven and so shaped his life and ours?

Or, perhaps, that panicked call was one of the early signs of the Alzheimer’s disease that would eventually take his life.

In 2009, my mother organized a trip to my father’s birthplace in Ukraine for me, my sister, and my brother. My father was supposed to come with us, but a cascade of errors triggered by his worsening Alzheimer’s kept him off the flight to Kiev.

I hadn’t been back to Russia since 1996, so nostalgia probably had something to do with the instant comfort and kinship I felt in Ukraine—with its kiosks crammed in the subways, the Burda-pattern dresses, cheap restaurants, broken sidewalks, and lax traffic regulations. Russian was spoken often, and I could understand most of the Ukrainian.

There, I found something like the optimism I’d binged on in the ’90s.

In Rivne, a local historian guided us to my father’s childhood home and the church with the century-old family plots still carefully tended by local villagers. The Ushinsky family estate—house, greenhouse, trees, landscaped grounds—had all been cleared long ago. Atop the hill was ploughed field, surrounded by bucolic views of farms, rivers, groves, and meadows.

How this soil is soaked in so much blood: shed in wars, purges, rebellions, holocausts. How much more can it absorb? Sifting the soil with my fingers left bits of brick. I brought them home to Canada and put them away in a box. Perhaps my children will find them?

If a connection to my father’s “Russianness” through place was possible, I thought when I returned home, then the Rivne region would be where I’d take my children. As much as I’d loved the crazy, turbulent life of Moscow, that all-too-brief trip to Ukraine had felt like a homecoming of sorts. That return never happened. A divorce and Ukraine’s own political upheavals perpetually postponed it.

My brother was lucky. He only had to walk the last seven kilometres to the border at Medyk and wait in line for seven hours. Men escorted the families of those with him to the edge, then said goodbye.

There are countless ties between the lands and their peoples. According to a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, 78 percent of Ukrainians identify themselves as Orthodox Christian, just as 71 percent of Russians do; entertainers tour both countries; friends, relatives, marriages, and business relationships criss-cross borders, and writers like Gogol, Bulgakov, or Ushinsky are claimed by both sides.

My father had lived to return to the place of his birth, to experience the fall of communism and the liberation of his church, and then to share the messy history of Russia and the USSR—his life work—with universities and seminaries in places ranging from St. Petersburg to Tomsk. With equal relish, he took to debunking neo-Stalinists romanticizing the Soviet era.

But his own cognitive decline—he passed away in 2014—spared him having to witness Putin’s Russia of today and the invasion which would surely have broken his heart.

Opposition journalists have launched YouTube channels and social media groups, which now have tens of thousands of subscribers and members. Recently, the February Morning TV channel took to the airwaves in Kiev to broadcast directly into Russia.

A new diaspora generation is fighting for a free future with today’s versions of shortwave broadcasts and camouflaged pamphlets. Would my father despair at the seemingly Sisyphean struggle or be inspired by the vigour of its renewal?

The resistance of the people of Ukraine to what is increasingly looking like Putin’s folly fans a spark of hope for post-Soviet Russia that had all but been extinguished.

Ukraine could still emerge as a crucible—and not for the first time—of promise and hope amid a historic outrage. The land of his birth may yet be a place of redemption for my father’s lost war.