Amid Chicago’s ongoing migrant crisis, where many wound up on police station floors and some residents have balked at providing beds for them, a group of City Council members on Wednesday proposed what they said is the solution.

The group of several Latino alderpersons are proposing a ward-by-ward search for unused buildings that, pending community approval, could be turned into temporary shelters where social workers could connect asylum-seekers and other unhoused people with transitional quarters and, eventually, place them in permanent, affordable housing.

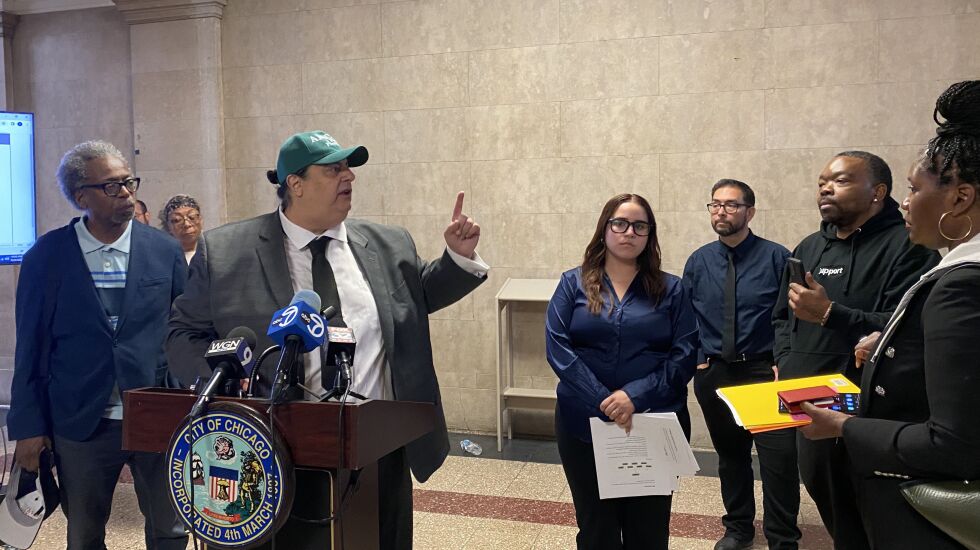

“We’re working in every corner of the city to address not only new arrivals but also existing issues that we have,” Ald. Byron Sigcho-Lopez (25th) said at a news conference at City Hall on Wednesday.

The plan would be an amplified version of temporary shelters that Sigcho-Lopez has set up in Pilsen and which he said is already an improvement on the “dire situation” of asylum-seekers and unhoused people staying in “inhumane conditions in police districts, in airports, in viaducts.”

The plan, of course, still needs funding and has yet to be introduced to the Council, but Lucia Calderon, Sigcho-Lopez’s chief of staff, said they have the support of the administration of Mayor Brandon Johnson — and already have a few places lined up.

The proposed locations are: four unused buildings at Daley College in West Lawn, where they said they could house 400 people; a vacant building at Archer and Kedzie avenues in Brighton Park, where they said they could house 30 people; and, in Little Village, a former CVS store and the Arturo Velasquez Institute, a satellite campus of Daley College, where they said they could house 200 people.

Calderon said Johnson had already toured the West Lawn and former CVS locations. and a tour of the Velasquez location was planned soon.

Newly elected Ald. Julia Ramirez (12th), whose ward includes the Brighton Park location, was among those attending to back the plan. Ald. Jessie Fuentes (26th) and Ald. Ruth Cruz (30th), who replaced Ariel Reboyras, former chair of the Immigration and Refugee Rights Committee, also were present.

Based on the cost to run the Pilsen facilities, a facility housing 200 to 250 people was expected to cost around $875,000 annually. Locations housing 30 people would cost about $80,000 a year.

The plan would be the latest way to deal with the migrant crisis in Chicago which started after Texas Gov. Greg Abbott began busing migrants from the border to Chicago last August. Since then, around 10,000 migrants have arrived in the city, according to the city’s Office of Emergency Management.

A plan to house migrants this summer at Wilbur Wright College in the Dunning neighborhood got a mixed reception from residents Tuesday evening at a public forum at the Northwest Side campus. Still, the plan got more support than efforts in other parts of the city, where plans to settle migrants have faced fierce backlash. A lawsuit has been filed to stop migrants from being housed at the vacant South Shore High School.

Some South Siders even crashed Wednesday’s City Hall news conference.

“The community says no,” said Val Free, founder of the Neighborhood Network Alliance, a group of South Shore block club organizations. “You’re presenting this plan without our voice.”

Another in Free’s group said that the plan didn’t address the “18,000 citizens returning from prison.”

“They have housing for us when we go to prison, but no housing for us when we return,” said Tyrone F. Muhammad, founder of Ex-Cons for Community and Social Change.

Sigcho-Lopez tried assuring the group that the plan included them, but the group wasn’t convinced. The two groups began talking over each other as reporters tried to ask questions.

“Let’s take CHA land and make affordable housing with it,” said Derric Price, founder of the African American Community Trust, taking the microphone. “There’s enough abandoned buildings in Chicago. Put those online.”

George Roumbanis, an educator at Daley College and City Colleges union president, stood up to show his support for the plan. “We can house hundreds of people right there where no community is impacted.”

Roumbanis, who immigrated from Greece in the 1980s, said it would be an improvement on how it was when he arrived; he wound up staying in a vacant building, where a local security guard duped him into paying rent. He considered it a bargain.

“Well, I didn’t know it was abandoned,” he said Wednesday. “But still, $75.”

Michael Loria is a staff reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times via Report for America, a not-for-profit journalism program that aims to bolster the paper’s coverage of communities on the South Side and West Side.