For almost a century, zoning has been the key tool used by urban planners to influence how our cities grow and change. Our newly published research looked at whether zoning is effective at guiding new urban growth patterns.

Zoning schemes vary, but generally consist of a map that classifies land into zones and a code that says what activities are permitted in each zone.

We found simply rezoning land for higher density is not enough to transform low-density and car-centric neighbourhoods into the mixed-use and walkable neighbourhoods envisioned in our planning schemes.

Read more: Wanted: family-friendly apartments. But what do families want from apartments?

A post-war model for guiding growth

Contemporary zoning truly developed after the second world war. Australian cities grew rapidly during this period.

A combination of large real estate interests and the emerging field of urban planning created low-density, car-centric suburbs. Urban plans called for standardised subdivisions and land uses, and engineering of streets and infrastructure.

Urban development was largely characterised by detached houses in residential suburbs. Large road networks separated these suburbs from commercial and industrial areas of the city.

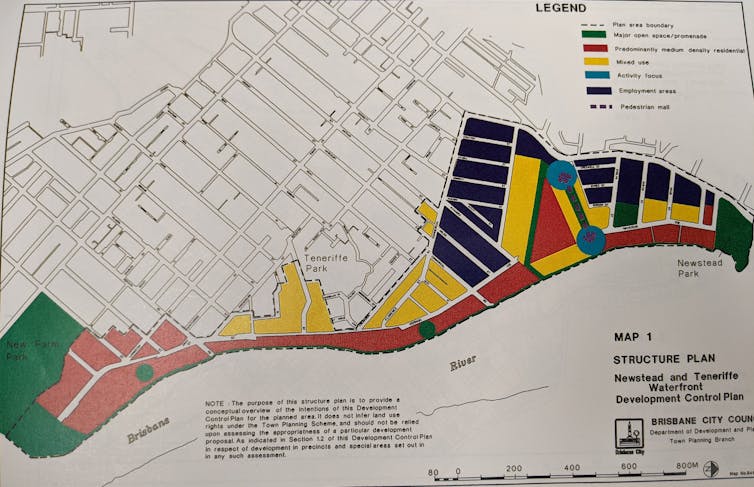

Fast-forward to the late 1980s and many cities began to introduce planning mechanisms to restrict outward expansion. Changes in zoning allowed for increased density and a mix of land uses. The aim was to encourage redevelopment of existing urban areas.

Read more: How we accidentally planned the desertion of our cities

What did the study look at?

Our research sought to understand how this new zoning, with the goal of increasing urban density, works in practice. We wanted to explore how differences in neighbourhood layouts influence outcomes.

To find out, we compared the redevelopment of six neighbourhoods over 70 years. Each neighbourhood has zoning that allows for high-rise apartments to be built. But the six neighbourhoods have different street, land parcel and land use patterns. This is because their initial construction happened in different periods.

Study areas included: inner suburbs with a gridded street pattern; inner and middle suburbs retrofitted for motorway and road-widening projects and large drive-in shopping centres; and suburbs built with motorways, streets following curved lines and drive-in shopping centres at the outset.

Our research looked at the city at three scales: street network, land parcels and building footprints.

What did the study find?

We found street networks were stable, except for government-led motorway projects. Large-scale disruption of street networks often requires acts of overt, top-down power. This can fundamentally alter the urban fabric of a neighbourhood – a highway cut one study area in half.

We found parcel boundaries were reconfigured for new development. Parcel size was reduced for most uses, except for commercial services like shopping centres.

We found a decrease in built structures over time, but an increase in their size. This was mainly due to larger buildings replacing smaller cottages and businesses. The total area covered by buildings increased substantially.

Read more: Why city policy to 'protect the Brisbane backyard' is failing

Some neighbourhoods were more adaptable to redevelopment than others. Less-connected neighbourhoods with large highways and cul-de-sacs, including those close to the city centre, had smaller increases in density than neighbourhoods with more grid-like street networks.

Read more: Road to nowhere: why the suburban cul-de-sac is an urban planning dead end

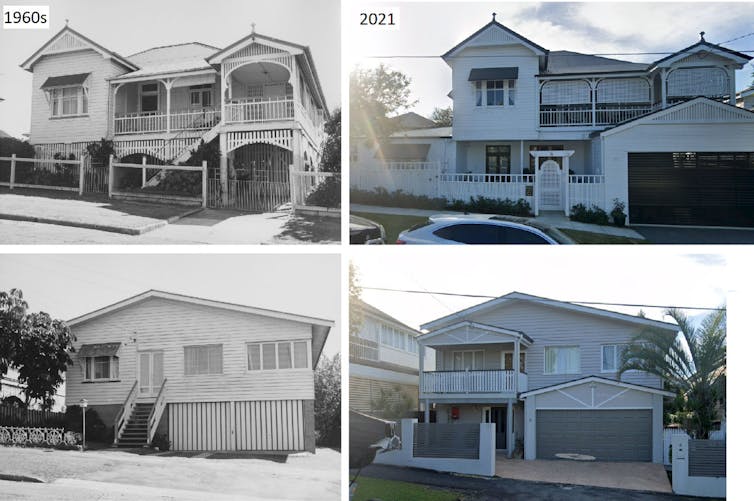

Protections on so-called character homes and successful campaigns against zoning for housing diversity mean multi-family buildings like apartments were concentrated in specific precincts, often next to low-density areas.

Character houses in Brisbane are dwellings built before 1947. Most inner-city parcels allow the construction of small apartments or townhouses if the development retains the original house.

However, our results show most parcels with character houses still contained only houses in 2021. This could be because contemporary renovations of houses significantly increase their building footprints, leaving little space for extra dwellings.

Read more: Whose ‘identity’ are we preserving in Auckland’s special character housing areas?

What does this mean for planning?

Our findings highlight the need to consider the existing built form and urban layout when applying generalised densification targets.

The suburbs of most cities in the developed world occupy more land than the gridded and denser city centres – and these suburban developments are not very adaptable to change.

Zoning alone may not be enough to catalyse redevelopment of suburbs that have disconnected and curvilinear street networks. Investment in infrastructure that improves transport connections may be needed if these areas are to be desirable (and practical) locations for increased urban density.

Read more: No need to give up on crowded cities – we can make density so much better

Rachel Gallagher has worked as a Senior Planner in Queensland's Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning.

Yan Liu receives funding from Australian Research Council (ARC).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.