When George Bileca was in high school in Romania in the early 2010s, he had dreams of becoming an architect. But then cars entered his life, and he decided to study automobile design in Coventry, U.K. instead.

Straight out of university, Bileca moved to Germany to further study modelling car bodies using 3D-design software. There, he met Leandro Bellone, who had worked with Rolls-Royce, BMW, and Mini, and had his own company, CryptoMotors, which designed NFT collections of digital cars.

Bileca, now 25, began designing car NFTs for CryptoMotors. Then, in early 2020, he and Bellone decided to set up a virtual dealership to sell their digital cars in Cryptovoxels, one of the many metaverses set up on the Ethereum blockchain. Neither man had any experience in architecture, beyond Bileca’s time spent designing structures in open-world games like Minecraft. Yet they worked together and built their dealership within the metaverse.

After realizing the potential to do the same for others, they built a new company: Voxel Architects, focused on designing and building structures in virtual worlds. “A lot of things contributed to the rise of the metaverse and its popularity,” says Bileca. “It was Meta, COVID, and the rise of NFTs.” Should Mark Zuckerberg’s vision become a reality, more than a billion of us will end up in his metaverse, or a competing one, by the end of this decade. And they’ll be bringing their spending power with them.

That promise is what’s led big businesses like JPMorgan Chase, Samsung, and others to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on parcels of land within existing metaverses like Decentraland, Cryptovoxels, and the Sandbox. But buying the land is just one part of the equation: Once you own it, you need to build something there so consumers will come. Which is where Bileca and other metaverse architects like Weronika Marciniak, 30, enter the picture.

Unlike the self-taught Bileca, Marciniak is a professional architect with more than a decade’s experience. As an architecture student in Warsaw, Poland, she was hired to work in the New York offices of REX Architecture. While there, she worked on the Ronald O. Perelman Performing Arts Center at the World Trade Center and on the Museum of the 20th Century in Berlin. She has since been employed at a number of leading practices around the world — most recently at the renowned Henning Larsen company in Hong Kong.

Last year, Marciniak noticed that the software she was using to render 3D computer-generated versions of the buildings that would end up getting built was largely the same as the ones that could be used to create buildings in immersive worlds accessed through virtual reality goggles. “I realized that I could actually see my projects in virtual reality and explore the metaverse,” she says.

She left her job and set up her own business, Future Is Meta, which is now fielding queries from businesses looking to build a physical presence in the digital world. One of her projects is a proof-of-concept music school — within Decentraland or The Sandbox — where visitors can learn how to create music by interacting with exhibits within the building.

“My speciality is buildings, but an interesting layer to it is the interactive layer, which doesn’t usually happen in real life,” says Marciniak. She believes she can provide something different to what’s already on offer. “Right now, the space is dominated by game designers or people who are interested in 3D design — but not necessarily architects,” she says. “The result is very often spaces that are hard to navigate or not necessarily thought through from the user perspective.”

Voxel Architects, Bileca’s company, now employs a total of 21 people, including three traditionally trained architects. “We have a team of voxel modelers” — those who design objects using cubes, or voxels — “and 3D modelers working in three of the biggest virtual worlds in the metaverse: Decentraland, the Sandbox, and Cryptovoxels,” he says. Voxel Architects, an official partner of all three of those companies, has built around 80 projects in the last two years alone — everything from art galleries to Christmas markets.

Business is booming

That business is likely to expand further, says Bileca. “One year in the metaverse is like five years in real life,” he explains. When he started designing buildings in the metaverse, parcels of land cost no more than $500. Now it’s impossible to buy lots in Cryptovoxels for less than $10,000. (JPMorgan data across the four main metaverses suggests that average land prices doubled between June and December 2021, to $12,000.)

The architects Bileca employs are mainly in their late twenties or early thirties, and one recently jumped ship from prestigious Spanish architecture firm Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura. “She said she really likes what we’re doing in the metaverse and wanted to join us,” says Bileca. “A lot of architects like this, because it doesn’t constrain you in terms of creativity.”

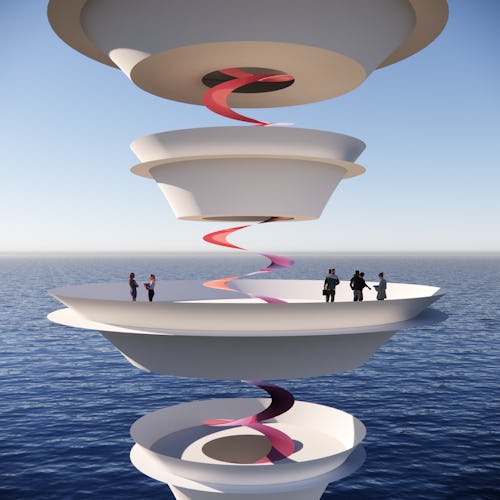

Many early-career architects get stuck churning out designs for “boring old residential buildings,” says Bileca. “Not a lot of people have the opportunity to put that creative engine in motion and create things like Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, or Ricardo Bofill.” That’s also what attracted Marciniak to set up her own metaverse-based firm. “The first thing is the freedom to design with different constraints that we don’t find in reality,” she says.

As well as the promise of ignoring gravity and government regulations, young architects are drawn by the promise of a sector on the rise — and the money that it can bring. Just like the world of NFTs and crypto, the metaverse is on the edge of a big bubble inflating, pushing prices sky-high. Crypto management firm Grayscale forecasts that the metaverse could be a trillion-dollar market opportunity.

While neither Bileca nor Marciniak were willing to share their rates for design projects in the metaverse, Marciniak tells Input she was approached by a client who had spoken to two other metaverse design companies. “They quoted around $50,000 for a building that takes a month,” she says. “It’s shockingly expensive.”

But as with IRL real estate, what seems pricey now may be considered dirt cheap in just a few short years.

VR Week 2022 is an in-depth look at the decades-long future of VR successes, failures, and innovations to come.

More VR Week 2022 stories:

- How one group is remaking sign language for the VR age

- Hot job alert: metaverse architect

- VR needs to address the huge motion sick elephant in the room

- Inside the volunteer 'police department' arresting people in VR

- The 9 best apps to get started working in VR

- There’s no VR internet in our future — at least not one we’d want

- The 11 best hardcore VR games you should play right now

- From ‘The Lawnmower Man’ to Meta: VR’s most important moments