Wang Xiaogang’s first encounter with a thinking machine two decades ago set him on a career path that would turn him into one of China’s foremost experts on artificial intelligence (AI).

A masters student in electronic engineering in 2001, Wang was visiting a laboratory at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) when his engineering dean Tang Xiao’ou showed how deep neural networks in computing could teach algorithms to mimic artistic techniques, transforming his photograph into a portrait with the signature styles of Claude Monet or Vincent van Gogh.

“It was eye-popping,” Wang said in an interview this week with the South China Morning Post from Shanghai. “I was a layman in AI” who had never seen anything like that before, he said.

The experience switched on his lifelong fascination with pattern recognition and machine learning, propelling him to complete a doctorate in computer science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and eventually to patent the technology for turning photographs into portraits. With his academic peers, Wang – who remains a professor at CUHK – co-founded SenseTime in 2014, turning the start-up into an AI powerhouse valued at US$8 billion according to data provided by Crunchbase.

SenseTime hired HSBC and China International Capital Corporation (CICC) to lead its initial public offering (IPO) estimated at US$2 billion in the city of its birth: Hong Kong. The stock sale would finance the growth of a company that is already applying its AI expertise in a multitude of applications and services, from face-unlock features on smartphones to diagnostic tools for X-ray and internal organs.

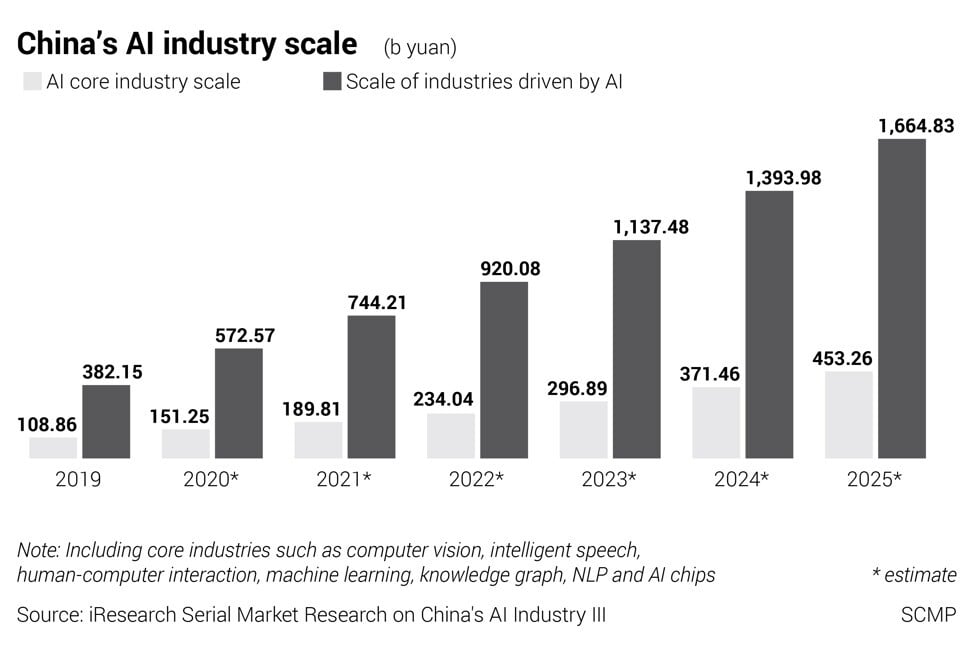

China’s AI industry – comprising computer vision, intelligent speech, human-computer interactions, machine learning, natural language processing and AI chips – is expected to triple to 453.26 billion yuan (US$69.8 billion) in value by 2025 from last year, according to a forecast by iResearch. A broader industry driven by AI may be as large as 1.66 trillion yuan by the same time, which underscores the strategic importance of the field in the “Made in China 2025” industrial master plan.

Wang, who declined to reveal his age, was born in the Hebei provincial capital of Shijiazhuang, near Beijing. He entered the University of Science and Technology in Hefei under a special programme for gifted children, graduating with an engineering degree in 2001. He has three patents on image processing under his name.

SenseTime was established in 2014, headquartered in Hong Kong. The company’s Chinese name is Shang-Tang, an amalgam of the character representing China’s earliest imperial dynasty with the surname of Wang’s mentor and MIT alumnus Tang. Their word choice for the company’s English name conveys their aspiration to keep apace with the times.

Tang, who also goes by Sean, still lectures in signal analysis and image and video processing at CUHK’s Faculty of Engineering. Xu Li, co-founder and chief executive of SenseTime, is another CUHK alumnus, with a doctorate in computer science. Xu and Tang were not available for this interview.

SenseTime brands itself as a technology platform that serves many industries from education to health care, instead of focusing on a single vertical that may quickly saturate, Wang said. The strategy is difficult for other companies to replicate, because many companies focus on narrow areas of development.

“It is difficult to find companies like SenseTime, because its history is so unique ,” said Wang, who is also managing director of SenseTime’s research laboratory. “SenseTime’s model and its biggest investment should be our basic infrastructure, our SenseCore.”

While the company invests in different applications, its two fastest-growing directions are its smart car business and its digital metaverse, or the sum total of all virtual worlds.

“The metaverse will change the way people live and socialise, and smart cars are actually undergoing a very significant change,” he said.

The company, which turns seven in October, now has 5,000 people on staff, 60 per cent of whom are in research and development. There are nearly 300 PhD holders and 36 professors among its employees. They provide the connections with academia that give SenseTime a steady pipeline of talent, said Jeffrey Ding, a Stanford University pre-doctoral fellow and researcher on Chinese AI.

SenseTime’s breakthrough came in 2014, when Tang and his CUHK team developed a facial recognition algorithm called DeepID, that could tell faces apart at an accuracy rate of 99.15 per cent, beating Facebook’s Deepface in a ranking using the Labelled Faces in the Wild (LFW) database designed for the study of facial recognition.

DeepID’s supremacy was a watershed moment for SenseTime. It also underscored the rapid growth of China’s AI industry, which was investing and developing facial recognition and surveillance features in smart-city systems across China. SenseTime and its industry peers Megvii, CloudWalk Technology and Yitu Technology would be dubbed the four “dragons” of China’s computer vision industry.

Armed with the accolade of beating the world’s largest social media network two years after Facebook’s US$16 billion stock offer, the CUHK team established a business in Hong Kong. IDG Capital soon came calling as an angel investor, becoming one of the first Series A funders of the start-up.

SenseTime would eventually receive US$2.6 billion in investments from 27 investors, including the Post’s owner Alibaba Group Holding, Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund Temasek Holdings, Masayoshi Son’s Softbank and even the Chinese real estate magnate Wang Jianlin’s Wanda Group, according to data provided by Crunchbase.

SenseTime’s algorithms are now used widely in China’s public security and surveillance applications, contributing to about 30 per cent of the company’s revenue according to local media reports. Surveillance is not a business focus, Wang said, declining to elaborate or provide a revenue breakdown.

“Most of China’s AI companies get their major orders from the government and related agencies for security or surveillance contracts, and a significant portion of this still comes from these,” said Zhang Yi, chief executive at Shenzhen-based iiMedia Research.

It did not take long for SenseTime’s role in China’s surveillance network to land in the crosshairs of the United States, particularly former Trump administration officials hunting to open new battlefronts with China in everything from trade to technology.

The US Commerce Department put SenseTime and 27 other Chinese companies on a so-called Entity List for export bans in October 2019, implicating them for their roles in “human rights violations and abuses” in the Xinjiang region. SenseTime denied the accusations, saying its technology has never been used for unethical purposes.

The doors of America’s academia and research institutions, even MIT where Wang and Tang both obtained their doctorates, slammed shut as soon as SenseTime appeared on the sanctions list. An MIT-SenseTime partnership announced less than 12 months earlier to fund 27 projects like linguistics and biology was put under review, as was MIT’s Intelligence Quest initiative, which sought to “advance research into human and machine intelligence in service to all humanity.”

The snub was “disappointing,” Wang said, but emphasised that SenseTime was “still looking to expand round the globe, with an open stance on every partnership and looking to extend the reach of our technologies abroad.”

“SenseTime aims to use AI to improve people’s lives, and we are complying with rules and laws in all the places where we operate businesses,” he said.

SenseTime has distanced itself from Xinjiang by selling its 51 per cent stake in Leon Technology, a Shenzhen-listed provider of surveillance technology that also appears on the US Entity List. SenseTime also sold a 49 per cent stake in SenseNets Technology, another Shenzhen company that helped to track the movement of more than 2.5 million people in Xinjiang.

“The indirect, and potentially more consequential, effect of the blacklisting was it raised a lot of questions about the ability for SenseTime to raise funds from international capital,” said Stanford University’s Ding.

CloudWalk, a Guangzhou-based software developer which installs facial recognition algorithms in automated teller machines (ATM), is aiming to raise capital in Shanghai. Beijing-based Megvii let its application to list in Hong Kong lapse in February last year, aiming instead to head to Shanghai’s Star market, where it hopes for a warmer reception and deeper pockets.

Besides geopolitical woes, the four dragons are also facing a saturating surveillance market at home with revenues squeezed by an increasing number of market-hungry competitors. China’s crackdown on Big Tech this year has put additional pressure on data rich AI companies, requiring them to carefully examine their practices under China’s newly introduced Data Security Law and the upcoming Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL).

Like many Chinese AI companies, SenseTime will have to face growing questions about the use of its technology. Since Wang’s entry into the field, the excitement and buzz around AI have been muddled by legal and ethical questions over abuse, the potential to inflame biases and personal privacy.

“We do not have access to customers’ data in general,” Wang said. “If our customers want us to process their data, we will safeguard it and prevent misuse and infringement of privacy. We are the first AI company in China to receive international and domestic information security standard certifications.”

The biggest challenge for AI companies, however, will be finding profitable business models and applications, said iiMedia’s Zhang.

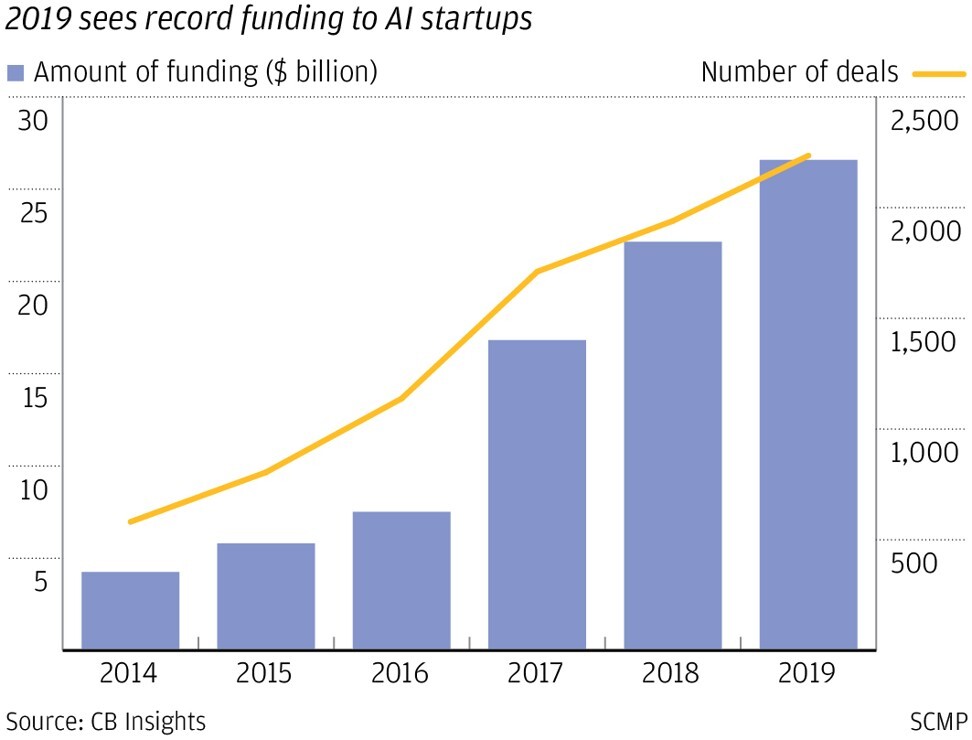

“These companies are in fact driven by capital; the hot money is huge, but so are the losses,” he said.

The way out may be to emphasise SenseTime’s business model of being a technology platform, instead of relying on narrow niches. The company has four major business areas: Smart Business, Smart City, Smart Life and Smart Auto.

Smart vehicles made it to SenseTime’s strategies in 2016. The company is developing level 4 (L4) autonomous driving technology and so-called smart cabins that can scan the faces of drivers for signs of sleepiness. The company has established partnerships with over 30 automotive brands including Japan’s Honda Motor.

“Our investment in the direction of cars will probably need a longer period of five to 10 years,” Wang said.

SCMP Infographic: AI ambitions in the Made in China 2025 industrial master plan

Other investments include smart city applications such as crowd and traffic monitoring while its SenseCare medical health platform is used in dozens of hospitals. The company has also been expanding globally, with offices in six overseas markets. Tang was even appointed to the board of Khazanah Nasional Berhad in July 2019, the first foreigner to advise Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund. He stepped down in April 2020.

The AI-powered image filters and special effects that wowed Wang twenty years ago are now standard features in ByteDance’s Douyin short-video platform. SenseTime has 80 per cent of this market, where its algorithms are in 160 different applications on 450 million smartphones used by 2 billion monthly active users.

“A few years before SenseTime was established, some of our employees could not explain to their parents what it was that they did at work,” Wang said. “Now it’s actually easy. I can turn on my smartphone and say: ‘Your life experiences are brought to you by the things we do.’ They can really feel these changes in [daily] life, all brought to them by AI.”