Looking down from the balcony over his cluttered shipyard in Aberdeen Harbour, 84-year-old shipwright Ngai Yau-chuen sighs at the forlorn sight of a battered sampan secured on a platform and waiting to be repaired.

The sampan – a small, traditional Chinese wooden boat – which has braved many vicious storms, has rotting planks and paint peeling off its hull. The damage will take four workers up to a week to fix, with the service bringing in only a meagre profit, Ngai says.

Sampans used to be a popular form of water transport in Hong Kong, especially in the 1950s when Aberdeen Harbour was packed with rows of such vessels, Ngai recalls. Sampans can be 4½ to seven metres in length and propelled by poles, oars or fitted with motors. On average, they can carry about 10 people.

But the traditional boat has lost its appeal, replaced by faster, more modern transport such as ferries and yachts.

“Nobody builds sampans any more. The existing ones are all we have left. If we lose one, it’s gone forever,” he says.

Ngai’s shipyard, Chuen Kee, which he established in his 20s, is one of the three remaining facilities in Hong Kong for sampan repair and maintenance. For him, a sampan means more than just business.

“The sampan was people’s means of living. It is a signature of old Hong Kong,” he says.

The sampan was people’s means of living. It is a signature of old Hong Kong – Ngai Yau-chuen, Chuen Kee owner

However, a proposal by the local district council for pavement works at the site on which Chuen Kee is located may force Ngai out of business and deal a lethal blow to the city’s twilight sampan industry.

According to Tsui Yuen-wa, a Southern District Council member, it currently takes half an hour for residents to walk from Shum Wan Pier Drive to Ocean Court along Aberdeen Harbour, but with Chuen Kee out of the way, it will only take 10 minutes. Many have complained about the inconvenience.

To save time, some people make short-cuts through the shipyard, but the path is narrow and unsafe, scattered with wooden planks and other shipbuilding materials. While neither Ngai nor the district council is certain of the exact area of land the yard occupies, it is reported to be more than 20,000 sq ft.

Tsui proposes building a walkway, either in place of Chuen Kee, or to have it pass through the shipyard.

“Taking into consideration the conservation value of the shipyard and sampans, we hope to reach a mutually beneficial agreement,” he says.

Chuen Kee has been on a short-term tenancy, with a renewal every three months. Its current hold on the place will end in September, when the district council will discuss the issue. As of now, the future of Ngai’s business remains unclear.

But if he loses his tenancy, Ngai says there is only one option left for Chuen Kee – closing down.

“It is impossible for us to move the shipyard which took decades to establish to this scale,” he says.

The ‘floating village’ days

At the age of 11, Ngai came to Hong Kong with his uncle from the mainland to pursue a better life. The city was poor and backward, with scant job choices, he recalls.

He started working as an apprentice shipwright at 15 in Aberdeen, one of Hong Kong’s oldest villages and an important fishing harbour on southwest Hong Kong Island. At 26, he established his own business – Chuen Kee Shipyard.

With more shipwrights moving to Aberdeen from places such as To Kwa Wan and Cheung Sha Wan, the area soon developed into a key shipbuilding centre with more than 50 shipyards at its height in the 1950s.

Orders flew in from all over Hong Kong, and business was so brisk that shipowners had to wait up to three months for their turn to get the vessels fixed, Ngai says.

“Aberdeen used to be so packed with ships that people could walk across the harbour using ships as a bridge,” he says.

Among the numerous vessels docked at the busy harbour were sampans.

As its name suggests, a sampan – meaning “three planks” in Cantonese – is a small flat-bottomed wooden boat consisting of a one-plank base joined to two other planks on each side.

According to the Marine Department, there are three kinds of sampans in Hong Kong: transport, fishing and outboard open boats. The last category refers to sampans powered by outboard motors.

Currently, Hong Kong only has 63 transport sampans. The rest are fishing and outboard open types, with 1,901 and 2,578, respectively, statistics show.

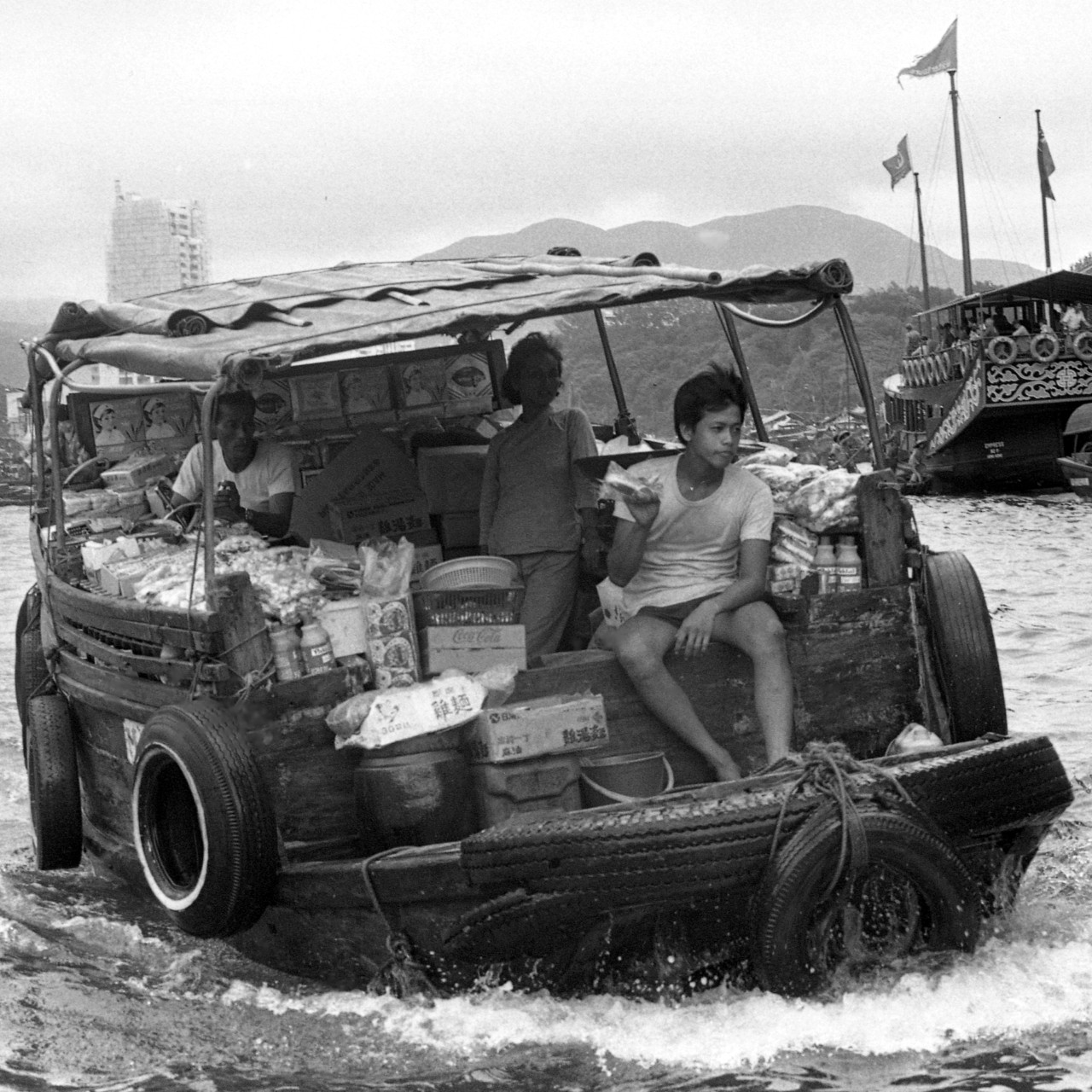

Decades ago, Aberdeen Harbour was teeming with such vessels, with many people living on them, forming a community known as the “floating village”.

Chu Yin-ping, 68, is a third-generation sampan operator with more than 40 years’ experience. Like many sampan dwellers, she grew up on one in Aberdeen. Each boat was a family home, where they would sleep and cook with no need to go ashore.

They could buy necessities from vendors who themselves operated sampans around the community, peddling goods.

“At night when all lights on sampans were turned on, the harbour was entirely lit up. It was so beautiful,” she recalls.

At night when all lights on sampans were turned on, the harbour was entirely lit up. It was so beautiful – Chu Yin-ping, 68, sampan operator

However, after the 1960s with the completion of housing estates and the proliferation of other industries which provided new opportunities, many of the sampan dwellers moved ashore to seek greener pastures. As a result, the number of sampans diminished, along with the unique way of life surrounding them, and this decline has never recovered.

In addition, a new bridge across Aberdeen Harbour was completed in 1977, providing an alternative for cross-harbour transport. Sampans have also given way to faster, more modernised transport modes like trains and ferries.

Ngai’s shipyard was forced to relocate from the island of Ap Lei Chau to the other side of Aberdeen Harbour more than 30 years ago because the previous site was reclaimed for property development.

Instead of shipbuilding, Chuen Kee’s main business now is ship repair and maintenance. Sampans account for about 30 per cent of its business, with the rest from cargo ships, fishing trawlers and yachts.

No new blood and meagre profits

According to Ngai’s second son Ngai Hau-on, 53, who helps his father run the shipyard, they have been struggling to maintain the sampan business.

Sampans require regular maintenance every four to six months. Normally a sampan takes four shipwrights up to a week to repair, mostly reinforcing or changing water-damaged wooden planks and adding nails to strengthen the structure, he says.

Currently, Chuen Kee receives an average of 20 sampan orders per month. The work is highly dependent on weather as it is done outdoors on ship cradles. The peak season comes at year-end as most sampan owners seek refurbishment for an auspicious new year.

Apart from the diminishing orders, the shipyard’s workforce is facing a serious ageing problem. Most of the shipwrights are over 60, and a few in their 50s like Hau-on are already considered young in the industry. Despite a lack of hands, Hau-on is hesitant to hire those over 70 as they may not be suitable for the highly physical and rigorous work.

Low salaries and the manual nature of the work discourage new blood from joining the industry, Hau-on says.

According to him, the average sampan repair and maintenance fee paid by customers is about HK$30,000 (US$3,846) to HK$40,000, while a major overhaul costs some HK$30,000 more – still far lower than works on luxury yachts which can bring in hundreds of millions.

Hau-on grew up on his father’s shipyard and started working there at 25. Due to years of toil, he suffered from a herniated intervertebral disc and had to undergo surgery last month.

In light of the declining prospects, most shipyards have abandoned the small business, but not Chuen Kee, which repairs over 70 per cent of Aberdeen’s sampans.

“Without us, how can we protect the remaining sampans?” the younger Ngai says, citing Typhoon Mangkhut last year, Hong Kong’s most intense storm on record, which laid waste to many sampans, especially in Sai Kung.

Today, dozens of sampans are still seen in Aberdeen Harbour, some being used as transport to and from larger boats while others are chartered by tourists for sightseeing.

Sampan operator Chu runs a boat tour along the harbour. She bought her sampan for HK$80,000 some 20 years ago. Together with her 92-year-old grandmother who can also handle the vessel, they provide 30-minute trips for tourists, mostly from mainland China who are eager to learn about Hong Kong’s traditions.

Some of their passengers have been prominent people and celebrities, including Queen Elizabeth, American singer Michael Jackson and players of Spanish professional soccer club Real Madrid.

“The sampan is Hong Kong’s culture, and we should be proud of it,” she says.

Apart from elderly sampan operators like Chu, some young Hongkongers are also concerned about the traditional boat’s future.

Andrew Tai, director of the Hong Kong Association of Sampan Conservation, says there is little effort made by the government and public to conserve it.

“Unlike trams and junk boats, you never find souvenirs featuring sampans,” he says.

The association is working with local artists, tour guides and schools to promote the sampan culture, Tai says.

For the senior Ngai, his shipyard is his home. He still lives there, in an elevated makeshift shack furnished with a bunk bed, a television and an air conditioner. He says the fresh, salty sea breeze and the clank of hammers on nails as shipwrights work are soothing to him.

Because of his age and weak lungs, he can no longer perform strenuous work and sometimes needs to wear a nasal cannula device for supplemental oxygen. But Ngai still regularly walks around to chat with shipwrights and check on their progress.

“Chuen Kee means everything to me. It’s my entire livelihood,” he says.