The night before June 6, 1944, fleets of warships moved in darkness towards the beaches of Normandy, France, for a massive strike, with Chinese naval officer Lam Ping-yu on one of the vessels.

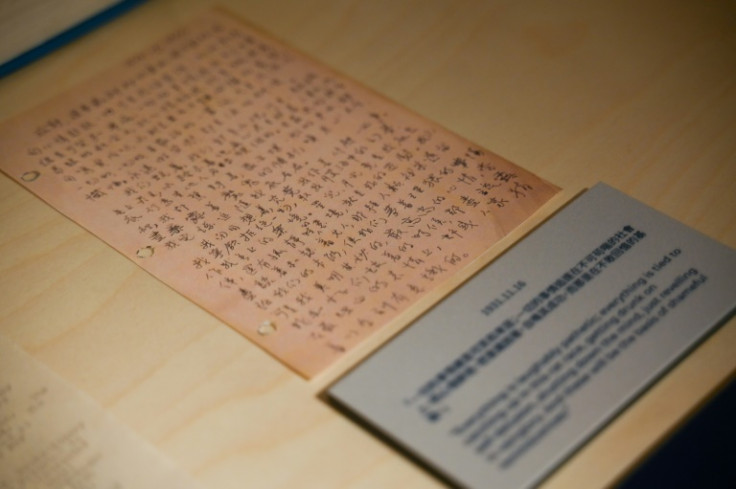

The ships were as "numerous as ants, scattered and wriggling all across the sea", Lam wrote in his diary. "Around 5 am: HMS Warspite was the first to open fire."

Lam's 80-page journal is the centrepiece of a Hong Kong exhibition launching this month, which for the first time chronicles the stories of 24 Chinese officers who helped Allied forces in their landmark D-Day operation.

Historians, documentaries, and pop culture have often focused on the British involvement in the largest amphibious military operation, which led to the end of Nazi occupation of Western Europe in World War II.

However, little is known about the Chinese naval officers sent to Europe for training.

Lam, then 33, was serving on the British warship HMS Ramillies which, according to his diary, opened fire about an hour after HMS Warspite.

"Throughout the day, Ramillies fired over 200 15-inch rounds, but the (Nazi) fort's cover and positioning kept it from annihilation," he wrote.

Digital copies of Lam's previously unseen diary will be displayed at the Fringe Club and the Chinese University of Hong Kong this month.

"We believe this historical episode belongs to everyone in both the East and the West," John Mok, 32, a public policy advocate and one of the organisers of the exhibition, told AFP.

"Sometimes we would ponder whether it was the Chinese helped liberate the West, or the West helped train the Chinese navy? It was actually 'you are among us and we are among you'," he said.

"I believe such inherent friendship is very precious these days as it's beyond politics -- the human solidarity in times of war."

The Chinese government selected 100 officers between 1943 and 1944 to receive training in the United States and Britain to rebuild China's naval force after it was destroyed by Japan, one of the Axis powers aligned with Nazi Germany.

The first batch of 24 officers sent to Britain included Lam and his comrade Huang Tingxin, whose son Huang Shansong will attend the Hong Kong exhibition.

"The strategic consideration at that time was to connect China's fight with the world's anti-fascist war... so that with the support from the US and Britain, China could better defend Japan's invasion," said Huang, who is a Chinese history professor based in Hangzhou.

Huang published a book of his father's oral history in 2013 but said he found Lam's diary more valuable for its accuracy, compared to his father's decades-old memories.

"Lam's diary is by far the only first-person, on-the-spot record about the 24 men's internship in Britain that is known to us today," he said.

He will bring his father's Legion d'Honneur -- awarded in 2006 for the elder Huang's contribution to France's liberation -- to lend to the exhibition.

"He always told me wars, in particular modern wars, were shockingly destructive," Huang told AFP.

"The importance of peace cannot be emphasized more."

Lam's diary almost ended up in landfills.

After the war, the naval commander lived in Hong Kong until the late 1960s and left the bulk of his personal items -- including the diary -- in his brother's apartment.

Rescued by a photographer and an amateur historian before the building was demolished, the diary caught the interest of Angus Hui, a former journalist who obtained a photocopy for his postgraduate study in Chinese naval history.

Hui met Mok last year, who suggested the stories "deserve a wider audience".

While conducting research trips to China, Taiwan, Singapore and Europe, where the veterans had settled after the war, they found that Hong Kong was the most suitable place for the exhibition.

Hui said he hopes the exhibition can address Hong Kong's place in today's world.

The former British colony -- once branded "Asia's World City" -- has fallen out of favour in recent years with Western governments, which have condemned Hong Kong over a rights crackdown following democracy protests in 2019.

But Lam's decision to come to Hong Kong "reflected the uniqueness of this place", Hui said.

"People may say Hong Kong is no longer relevant... But from history and from our own experience, we find Hong Kong still relevant."