When Charlotte Bonner saw Barbie last summer, she was blown away by how much the film spoke to her. “It was very motivational,” says Bonner, a marketing assistant and book blogger in Gloucestershire, England. “The themes were very poignant for the time that was going on.”

An avid reader, Bonner likes to annotate books with different colored pens and highlighters. While watching Barbie, she remembers thinking to herself, “This is something I could annotate quite a lot in.”

A few months later, she got her wish. In December, Faber & Faber published the Barbie screenplay as a 138-page paperback, with full-color photos and a new introduction by the film’s co-writers, Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach. “I went round to all the bookshops and just happened to find it,” Bonner recalls. Meanwhile, in a real-life literary Barbenheimer, her father bought the Oppenheimer screenplay — also via Faber & Faber, which has published most of Christopher Nolan’s screenplays since 2001’s Memento. “He’s very much a history person, and he likes to read a lot,” Bonner says of her dad.

Increasingly, blockbuster movies aren’t just making an impact at the box office or on streaming. They’re resonating at bookstores, too, many of which prominently displayed the Barbie and Oppenheimer screenplays last year as though they were buzzy new novels. The sales seem to justify this strategy. In August, Variety reported that the screenplay to Nolan’s acclaimed biopic was selling out fast on Amazon.

“I think it sold 19,000 [copies] in the first few months,” says Walter Donohue, senior editor at Faber & Faber. “Mainly in America, because there was so much interest in the film. I think a lot of people bought the scripts because they wanted to get more details about what they might have missed when they were watching the film.”

Others who bought the script were aspiring screenwriters seeking inspiration — which explains why they would choose the screenplay over the award-winning book on which it’s based.

“I use it for reference only,” says Markus McLaughlin, a Boston-based screenwriter and movie buff who cites Oppenheimer as his all-time favorite film. He bought the script in Kindle format and keeps it open in a window while writing his own scripts. “I am studying Nolan’s writing style and seeing if I can write in that style.”

Decades ago, such eager screenwriters had to get their fix from the guys selling bootleg movie scripts on the streets of New York. Today, they can buy the real thing, albeit in slightly pricier form. (In the states, Oppenheimer’s screenplay retails for around $17.95.)

“I think the audience for these books is overwhelmingly other screenwriters, since the format is kind of off-putting to people who aren’t directly familiar with it,” says Truman Capps, an L.A.-based screenwriter of (thus far) unproduced scripts.

Capps tends to find popular screenplays for free floating around Reddit and other message boards, but he does own The Hudsucker Proxy, a gift from a friend.

“If the bulk of the proceeds from a screenplay book flow directly to a writer, then they should absolutely publish more of them,” Capps says. “In my experience, the industry has developed very efficient systems to deprive writers of the money they’re owed.”

That question of compensation generally comes down to whether a screenwriter retained the screenplay rights in their deal with the studio. (Donohue says he often negotiates publishing deals with the screenwriter directly, as they often retain those rights.) But in addition to money, these book deals can bring a screenwriter the legitimacy of knowing that their work transcends formats and resonates on the printed page — a curious inversion of the validation a novelist may feel when their book gets adapted on the big screen.

“It Was Like an Earthquake.”

The screen-to-book pipeline is booming, but it’s not a new invention.

For more than 30 years, Faber & Faber has specialized in publishing books about film. First came its acclaimed book-length interviews with filmmakers, a tradition that began in the late 1980s, after director Michael Powell saw Martin Scorsese giving talks about his career in England and suggested they could be a book. That led to 1989’s Scorsese on Scorsese; similar volumes — Malle on Malle, Lynch on Lynch — soon followed.

Around that time, Donohue realized there was a market of film fanatics eager to buy scripts for buzzy new films. By the mid-1990s, Faber & Faber had published screenplays by emerging filmmakers like Whit Stillman and Hal Hartley. It had also begun publishing the gleefully perverse scripts of the Coen Brothers, beginning with Miller’s Crossing (1990) and Barton Fink (1991).

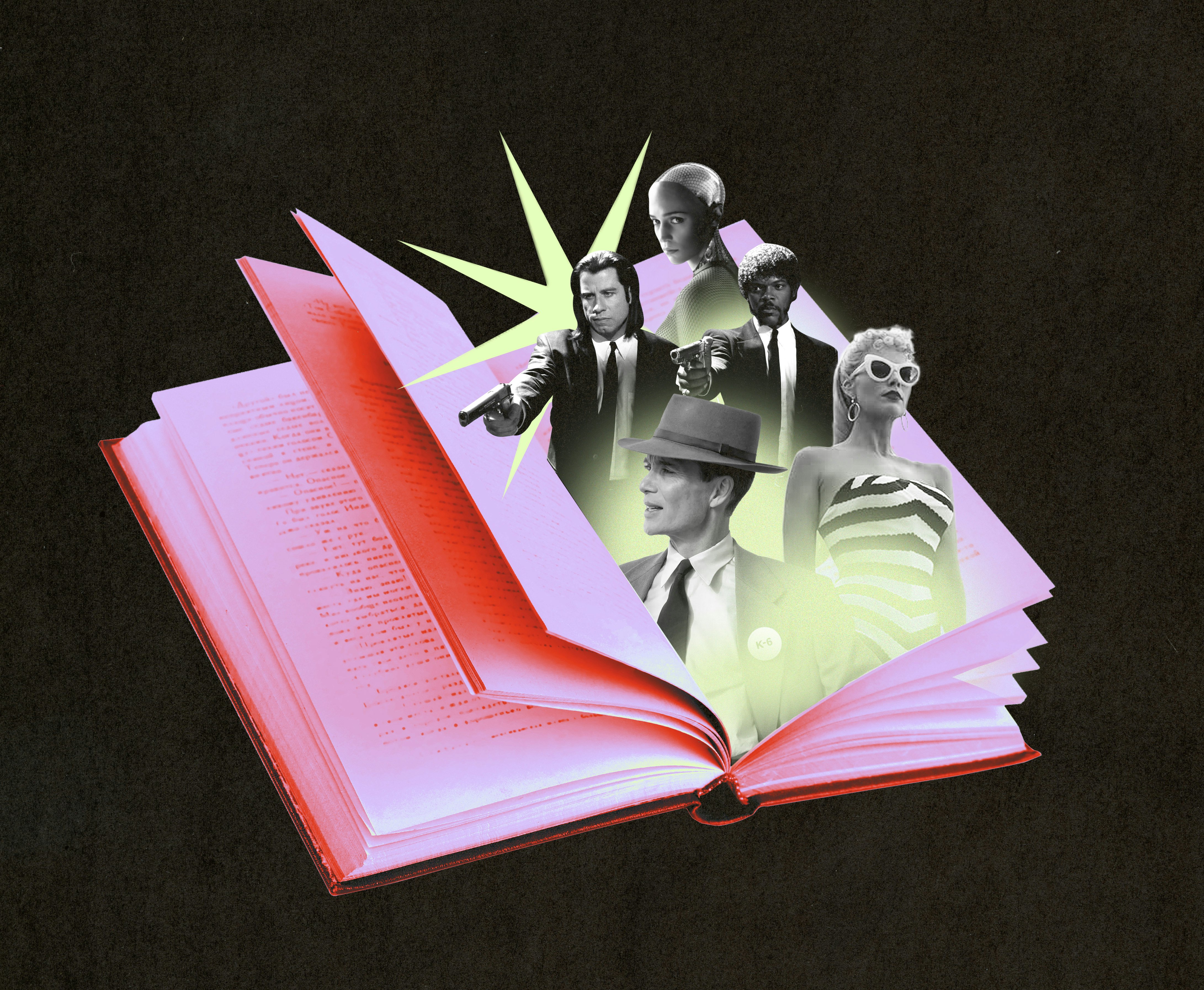

“Eventually, word got round that Faber was doing this,” Donohue says. “Then filmmakers would approach me about them. Whenever we published a screenplay, they sold.” For years, Faber & Faber’s film list “kind of hobbled along, not making that much money — until Pulp Fiction occurred.”

Not just a landmark for independent filmmaking, Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 film also became a massive hit for Faber’s screenplay series. Tarantino’s flashy dialogue and encyclopedic cultural references crackled on the page. “It was like an earthquake,” Donohue says. “We sold 120,000 copies. Most screenplays sell maybe, at the most, 5,000.”

In 1995, Newsday reported that the screenplay had already sold 55,000 copies — more than any other in British publishing history — while fans lined up for hours when Tarantino visited London for interviews and book-signings. “The Pulp Fiction screenplay is a phenomenon,” a Faber publicist told the newspaper, noting that it had been reviewed in “serious newspapers and magazines as if it were a fiction book.”

Donohue’s instinct to treat screenplays as literature was validated. In his view, the success of Pulp Fiction — as well as Reservoir Dogs, the script of which Faber also published — signaled the arrival of a new generation of aspiring filmmakers.

“There was something in the zeitgeist,” Donohue says. “Young people wanted to be filmmakers. They didn’t want to be novelists or playwrights. They suddenly wanted to become filmmakers. But the other thing was, Tarantino’s scripts were very complex. The structures were not simple. The language was very unconventional. People were quoting words, phrases, things from the films. If you wanted to be a filmmaker, you had to watch videos, and you had to read screenplays — if you decided to sidestep trying to go to film school.”

After Pulp Fiction, the film list at Faber & Faber became Donohue’s main focus. He kept his ear to the ground, searching for movies that could translate to bookstore shelves. In 1998, a filmmaker told him he had just seen a new movie called Rushmore. “And he thought the director was someone that Faber should publish,” Donohue says.

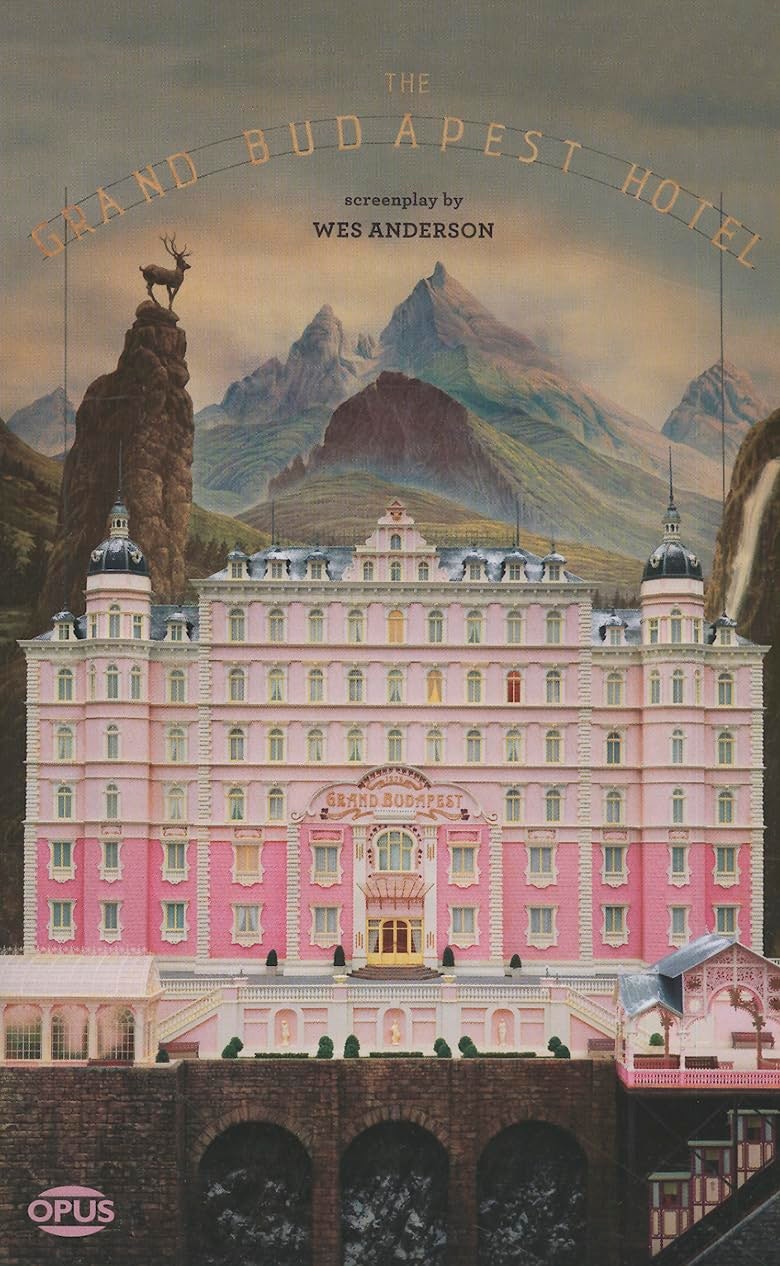

So began Faber’s on-and-off association with Wes Anderson, whose screenplays it has continued publishing in recent years. The publisher has also consistently published the works of the Coen Brothers and, of course, Christopher Nolan. “Whenever we did the Nolan screenplays, Christopher was very good about giving us storyboards to put in it and photographs,” Donohue says.

As for why certain filmmakers seem to work better on bookshelves than others, nonlinear structures, witty and eccentric dialogue, and intricate plots all seem to be common threads.

“There’s something interesting about the structure,” Donohue says of the types of screenplays that succeed as books. “It kind of entices would-be filmmakers to read them just to get a sense of how interesting a structure is. Christopher Nolan, Wes Anderson, the Coen Brothers — they’re the three filmmakers whose screenplays keep selling.”

Donohue strives to keep the books relatively affordable. “Faber’s attitude was always like ‘They’re not expensive because it’s for people who want to be filmmakers. They can put them in their backpacks.’”

“A Wild, Wild West”

To a ’90s kid, these screenplay books may resemble a classier, gentrified spin on the movie novelizations of yesteryear. Though novelizations of popular films existed as early as the 1920s, these mass-market paperbacks were inescapable during the 1980s and ’90s, converting blockbuster franchises into kid-friendly books.

They were cheap, too — my copy of the Night at the Museum novelization still carries a $4.99 Borders price sticker.

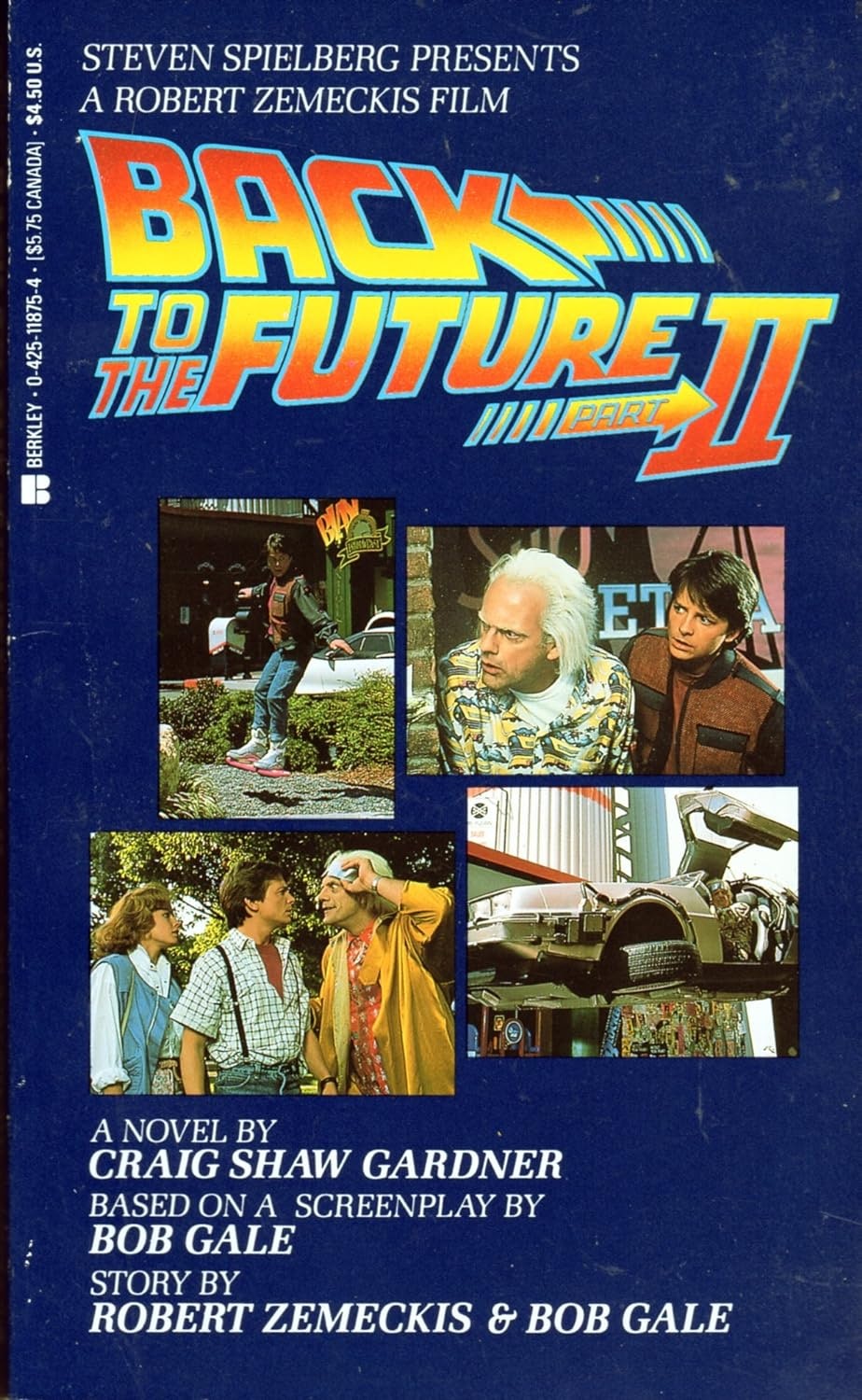

What made these novelizations both interesting and sometimes vexing to studios is that they didn’t always line up perfectly with the film. “It was sort of a wild, wild west,” says pop culture writer Mike Duquette, who writes the Hollywood & Spine newsletter about movie novelizations.

Back to the Future is a great example, Duquette says. “Unfortunately the author has passed away, but I am positive he was given photos of Eric Stoltz as Marty McFly and was told, ‘OK, run with this.’ The big tell is the continued dig at how odd it is that Marty’s wearing green shoes in 1955, instead of the bit about his ‘life preserver’ vest. Most of the pictures of Eric that have been released are in black and white, but it’s believed that his shoes were indeed green.”

Somewhere around the late aughts, the humble movie novelization fell into decline. In Duquette’s view, we hit an inflection point in 2008 — the year major blockbusters like The Dark Knight got novelizations, but also the year the Marvel Cinematic Universe was born. While Iron Man and The Incredible Hulk yielded novelizations, most subsequent superhero movies did not. Duquette theorizes that the MCU’s obsession with preserving canon and avoiding spoilers wasn’t compatible with the freedom traditionally afforded to novelization authors.

“Gradually, as the Marvel Cinematic Universe pushed other movies out of theaters, other novelizations kinda got pushed out, too,” Duquette says, noting that last year’s Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny was the first in the franchise not to get the novelization treatment.

But the movie novelization isn’t totally dead. Once again, Tarantino is a pioneer of the film-to-page reversal: With 2021’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood: A Novel, he became the rare director to pen a novelization of his own movie, remixing the lore and backstories to his heart’s content.

“Shrines to A24”

In the years since movie novelizations went the way of the CD-ROM, no studio has capitalized on fans’ desire to engage with their favorite movie on the printed page as savvily as A24.

In 2019, the buzzy art-house studio launched its book imprint, publishing lavish, hardcover “shrines” dedicated to three films that put the studio on the map: Moonlight, Ex Machina, and The Witch. The idea for the series originated with A24’s creative director, Zoe Beyer. Despite some internal skepticism, the first three sold well and prompted the company to hire a head of publishing. The studio has since added eight more to the collection, including Ari Aster’s breakouts Hereditary and Midsommar, and — the top seller so far — Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird. (A24’s publishing team declined to comment on the record for this piece.)

At $60 apiece, these screenplay books are pricier and more expansive than the Faber & Faber equivalent. They’re boutique items, containing not just the screenplay but also critical essays, behind-the-scenes materials (for instance: Gerwig’s personal letter to Dave Matthews), and set photography. The studio grants filmmakers ample say in the process — some screenwriters provide the original shooting script for publication, while others will go back and edit the script so it matches what ended up in the final cut.

A24 also approaches the selection process differently. While Faber often publishes screenplays concurrently with the film’s release — not knowing whether or not the film will be a success — A24 waits to see which of its films resonate the most. Generally, the studio likes to wait until a film has been out in the world at least a year before deciding if it warrants a book.

Until now, the A24 screenplays have been available only through the studio’s online shop, making them prohibitively expensive to fans outside the United States. But that’s about to change. In May, the independent art publisher Mack Books announced a global distribution partnership with A24.

What the partnership means is “the screenplays are gonna be in bookstores around the world for the very first time, from September,” says Liv Constable-Maxwell, commissioning editor at Mack.

“What we’re realizing is that audiences are really hungry for books that take you behind the scenes of the worlds of their favorite films or directors,” Constable-Maxwell adds. “I think that’s why [screenplay books] are so highly sought after, because they really give people a very distinctive engagement with the film offscreen.”

“A Literary Barbenheimer”

Shortly after Oppenheimer was announced as Nolan’s 12th film, Faber & Faber made arrangements to publish it. It was not its first time publishing the director’s work.

But Barbie wasn’t part of the plan. Faber had no plans to publish Gerwig and Baumbach’s screenplay until well after the “Barbenheimer” phenomenon convinced thousands of moviegoers to make it a double feature.

“And then Mattel approached us,” says Donohue. “And said, ‘Would you make an edition of the screenplays?’ Because [Warner Bros.] wanted it for the Oscar nominations.”

According to Donohue, Mattel — Barbie’s corporate creator — approached the publisher in October, months after Barbie came out, and spurred the idea of the screenplay book. (Mattel did not respond to a request for comment.)

The publisher acted quickly and, following a star-studded launch party, the book hit stores by mid-December. While most of the books were delivered to retail businesses, Faber had some set aside and shipped directly to Warner Bros. so the studio could send them out as part of its award-season campaign.

Meanwhile, Charlotte Bonner, the Barbie fan, picked up her own copy in time for Christmas. It’s currently in her queue of books she plans to annotate. Bonner reflects, “It’s nice to be able to flick back through your notes, and in the book itself, and go, ‘This is what made it so important and poignant at the time.’”