For the better part of two decades, Media Molecule has been in the business of breaking down creative boundaries: not just by placing game development tools in the hands of its audience, but by finding ways to actively encourage players to become makers. As such, it's hard not to view the opening of Tren – the studio's last major release for Dreams, as it turns its attention to a new project – in metaphorical terms.

As a diminutive wooden train finally manages to burst free of its box, breaking open the cardboard flap holding it back, it's only natural to think of Toy Story, and the familiar notion of an old plaything coming to life when no one is around. But as polystyrene curls are sent scattering, we see instead a dormant creative spark being unleashed, the barrier of self-doubt forced aside. And the winding track before this tiny locomotive, stretching out into the distance? Well, that's the long, serpentine route this nascent idea must take to reach its ultimate destination.

Nod on

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more in-depth interviews, reviews, features, and more delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge magazine.

Perhaps that's reaching a little. But the more we see and play of Tren, the more it feels like a game that simultaneously reflects the studio's 'play, create, share' ethos; the remarkable piece of software that hosts it; and, just as significantly, the artistic linchpin behind it. For John Beech, recently appointed the studio's creative director, this marks – for now – the culmination of a development journey that began in unusual fashion. Here at Media Molecule, however, his new role feels the most natural outcome of all.

Beech, after all, first attracted the attention of his employer of 14 years as a member of its community. A builder by trade, he spent his free time doing construction of a very different kind, making LittleBigPlanet stages on his PlayStation 3. One particular level, grandly named Future Warzone: Battle For Little Big Planet, first got him noticed. "I'd made this basic flying spaceship that comes in and lands," he recalls. This might not seem like anything out of the ordinary, but consider that tools for making flying objects simply did not exist. "I'd discovered a glitch where you could make pistons invisible, essentially," Beech grins. "Everyone was like, 'How did he make a spaceship fly?'"

The trick was enough to grant him an audience with Media Molecule staff, who wanted to ask him the same question – plus a few more. "I had a borrowed suit because I've never had an interview in my life," he says. "I'd just been a builder up until that point. I arrived wearing a backpack with a PlayStation 3 in it." Studio director Siobhan Reddy remembers the day well. "I'll never forget it – it was a really hot day, we didn't have any air conditioning in our old studio, and we were all flustered because we were excited to meet John, because of everything that had happened." Within minutes, she says, they'd decided to hire him.

When studio co-founder Mark Healey stepped down from his position as creative director, the choice of his replacement was an almost equally straightforward decision. "The work that John had been doing on Tren demonstrated skills of being able to set a strong creative vision, to rally a team behind that, and to develop it in a way that was very true to the best version of MM and very collaborative," Reddy explains. "That felt like what we needed, and I think John is a unifier: he's got a lot of the things that you need within that leadership role." The response within the studio – and wider community – seems to have rubber stamped the decision to appoint Beech. "There were quite a few big cheers," she adds. "And it's just a real joy to collaborate with him, because John's MO is to be a collaborator. And I think that's what the studio really needed, particularly when you've been going through some…" Perhaps mindful of the Sony PR manager hovering nearby, she pauses momentarily. "Changes."

That's an understatement. We get the distinct impression from the atmosphere at the studio that Beech's appointment has been a galvanising moment, after what has been a challenging transitional period for the Guildford studio. Having helped found MM in 2006, Alex Evans left in September 2020, with Karim Ettouney and Healey following him out of the door earlier this year (the fourth and final co-founder, David Smith, remains as technical director). A week before Healey's departure, it was announced that Media Molecule would be ceasing live support for Dreams in September, bringing to an end three years of in-game events and updates.

With all that in mind, it feels as if there is a lot riding on a game that was never really intended to be a send-off for Dreams. In fact, development began shortly after work finished on Art's Dream, the two-hour musical showpiece that launched with Dreams to show what was possible to make with the tools it was offering to budding creators. The introduction of the Friday Jams was intended to do similar for Media Molecule's own staff, encouraging them to build new experiences for Dreams. Nothing if not ambitious, Beech began by asking himself a single question: "I just thought to myself, 'How can I make a triple-A-quality game on my own?'"

Then his more practical instincts kicked in. "I really love sculpting realistic things in Dreams – that tactility really talks to me," Beech says. So, given his previous career – and indeed, as someone who shares his surname with a type of timber – what could be a more natural material to work with than wood? "I know exactly how it looks, what the grain looks like, and how it functions in a sort of mechanical sense." As for narrative inspiration, Beech decided to look closer to home. His home, in fact.

Recalling his father's fondness for trains – a love that continues to this day – he began to assemble a toy train set within a virtual attic. "It sounds weird [given the triple-A goal] but I was always trying to take the path of least resistance. I chose wooden trains because I could get away with slightly wobbly physics; I could get away with not sculpting hyper-realistic trains because these could still look realistic in their own environment. Everything was a really considered pragmatic solution to what I was trying to achieve." In other words: the pistons are invisible here, too.

This hobbyist project became a labour of love. Beech was already in the process of renovating his house, while he and his wife were about to welcome their first child into the world – both of which would factor into the game's story, as the attic develops over time. "You'll start seeing plasterboard going up, and bits of two-by-four. Eventually, you're in this fully decorated loft conversion," Beech says. But despite having so much going on in his personal life, he found time to beaver away at the game ("I was 3D printing Trens while my wife was going into labour," he laughs) before showing the results to his colleagues.

"I'm an oversharer at the best of times," he says. "It was maybe six months in, and Siobhan and my predecessor, Mark [Healey], saw it and they were just like, 'This is really awesome, John. We want you to do something with this'. And so the leisuretime diversion soon became a nine-to-five concern, and as the concept began to gain momentum, more and more staff jumped aboard.

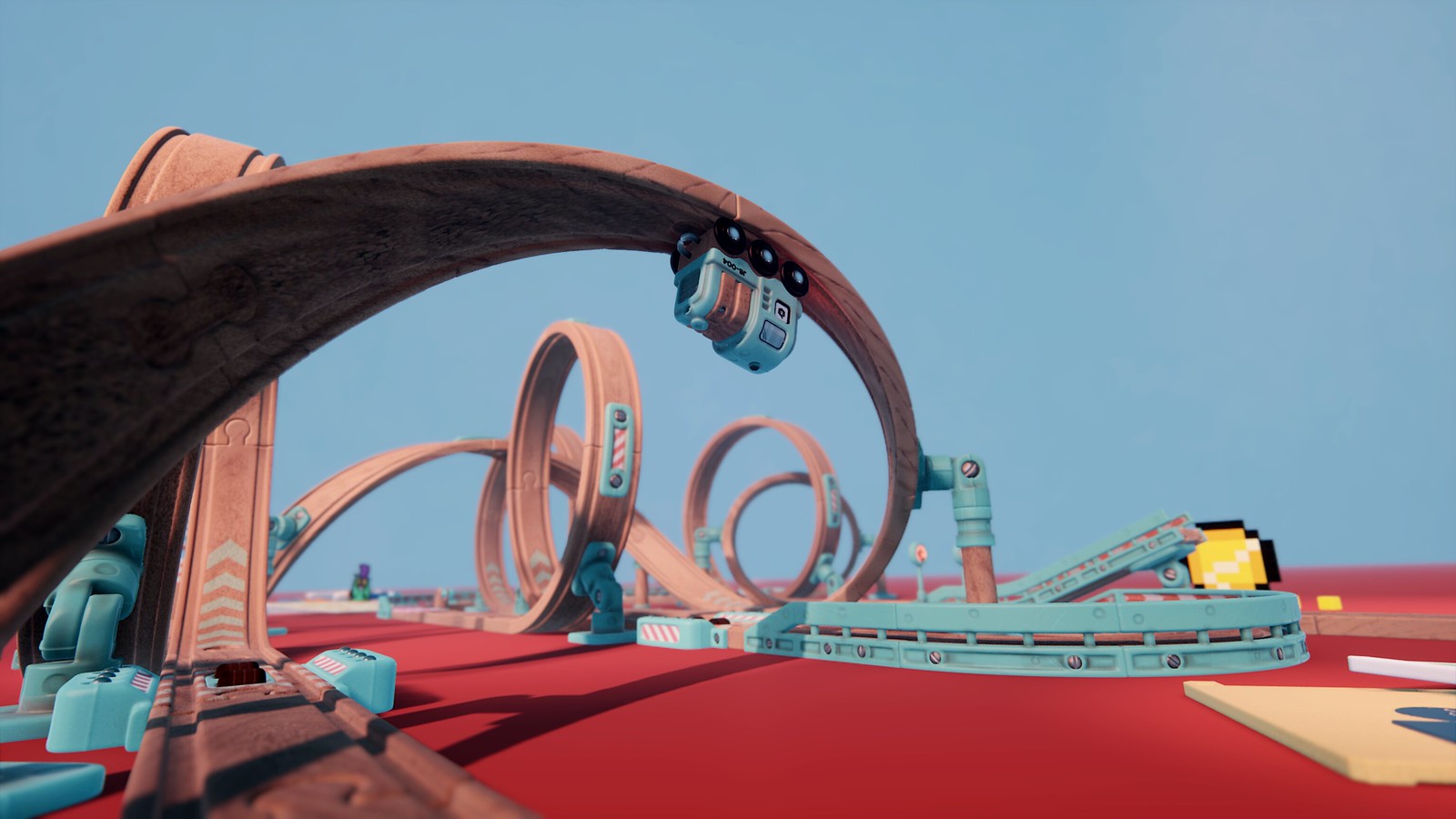

The best part of three years later, the final result wears the weight of its role as a swan song lightly. "I had in my mind the kind of people who play with trains," Beech begins. "And it's like the adult who plays it really realistically, where they operate a full-on train service. And then there are the kids, who just want to zoom off the track and do stunts and jumps." Both types of player, it's fair to say, are well served here. For the grownups, there are longer, more considered puzzle-focused courses that simply demand you figure out how to get to the end. But for those who just want to see trains go fast, there are obstacle courses with corkscrews and loop-the-loops that require injections of boost to successfully negotiate. Although you sense the inevitable crashes brought out on by taking a corner at high speed, ploughing into a hazard, or failing to land a flip after accelerating up a steep ramp might be even more entertaining to those players than the successful runs.

Most of the stages in Tren offer a captivating mix of the two, with sections that require more careful control and others that demand you go full steam ahead. Picking up carriages all but forces you to slow down, as do sections where you must pause while sliding rails into position. You must time your advances between other trains (or indeed Trens) as they patrol looping sections of track. You'll switch rails on the fly, pick up loose cargo (brown objects with a soft sheen that resemble nothing so much as an emptied-out pouch of Revels), trigger pressure plates that cause parts of the course to raise and flip and slide into new positions, and tentatively navigate tilting sections. Magnetic tracks allow you to pull off gravity-defying manoeuvres, while you'll need sufficient momentum to decouple wagons so they can slide into position beneath barriers.

Playful end-of-stage flourishes abound: in one stage you're encouraged to launch the Tren through a basketball hoop, topple a card pyramid or land back inside a cardboard box. And to add extra impetus to return, there's a grading system based on how quickly you complete a stage – though in some cases going full pelt is a bad idea, since seconds will be shorn off your finish time for each carriage that is still intact when you cross the line. It's not just the lovingly rendered games and figurines scattered about each stage that remind us of classic toys: the stages themselves owe as much to Screwball Scramble and Scalextric as to old-fashioned train sets.

But as much as Tren's narrative centres on the idea of childhood favourites being passed down from generation to generation, it naturally owes a debt to more contemporary forms of play, too. If the lighthearted tone initially recalls Joe Danger, when the challenge begins to ramp up it feels almost like Media Molecule's Trials – the game's exacting later tests requiring similarly fine control of forward and reverse momentum. Indeed, each chapter features an 'expert spur'; rather than advancing the story, you can stick around to tackle a string of harder stages. And there's a survival mode which tasks you with keeping your train running down a track composed of procedurally generated chunks while enemy locomotives give chase.

Tren is satisfyingly varied, then: this might be Beech's vision, but it's quite clearly a collaborative effort, one that speaks to the tastes and tenets of the team that built it. "One of the things I love about Tren – actually, the only other game we've worked on like this was LBP – is that you can tell which designer made the levels," Reddy says. "You can be like, 'Yeah, that's a Steve level; that's a Maggie level'. And I love that because you get to know people and that stuff really comes through."

It is surprisingly substantial, too. From beginning to end, it should last most players around six hours – three times the size of Art's Dream. Additionally, completists who want to earn all three 'grade pips' on every level can expect their hour count to nudge double figures. We ask Beech whether Tren reached that size partly out of necessity, knowing that – with the studio having somewhat reluctantly called time on live support for Dreams – this would effectively be an opportunity to say goodbye. "Not so much, no," he says. "Tren was probably as scoped and as big as it was going to be long before that happened – it just happened to coincide with being the last thing. But what I had in my mind was always where it ended up, you know? And MM and Sony were good enough to give me the opportunity to get it to where I thought it was a complete game."

However, that decision gave the Tren team the opportunity to properly commemorate Dreams. With levels themed around LittleBigPlanet and Tearaway, it already doubled as something of a potted history of the studio. But now Media Molecule had the chance to give something extra to its community, "it felt only right to respect the past to move forward," Beech says. "As it became clear that Tren was going to be our last big release in Dreams, I made sure to include as many Easter eggs to the community as possible. So there's one area near the end of the game where you can go up on this shelf in the bedroom, and there are Impys [the annual awards given out by the studio to the best community creations] and a VHS from the 2018 E3 live performance."

The gifts to the Dreams community don't end there. After all, this wouldn't be much of a Media Molecule game if you could only play it. Beech assembled Tren much as you would build a traditional train set, putting it together piece by piece. "I just started building the kit in its final form and started making levels with it straight away," he explains. "It was like, 'Oh, I need a ramp, I need a corner', and each time I would just add to the kit." As such, by the time development on the game had finished, he and his team had amassed over 550 elements – by orders of magnitude the biggest kit in Dreams to date. And every one of these pieces will be available to players to build their own levels, to keep Tren running long after it has run out of officially supplied track.

In the DNA

Indeed, similar could be said about Dreams itself. Tren might be Media Molecule's last Dreams release, but it's by no means game over. The studio's in-house curation team is continuing to surface the pick of the community creations via its Impsider blog, while this year's move to a more stable server, alongside a sweeping overhaul to its animation tools, are encouraging signs for its user base – several of whom have already set up community events of their own. An update to usage terms will now let creators take some of their original creations – music, animation, films and art, with restrictions – beyond this walled garden for their own personal use, and perhaps even monetary gain.

That latter point feels particularly pertinent. The studio's final message to fans talks openly of the disappointment it feels at having to leave Dreams behind sooner than it ever expected – its failure to "define a sustainable path" speaking to the way MM never quite managed to square the circle of balancing the needs of a commercial product with its desire to create the modern equivalent of an artists' collective. Yet if there's a sense that Dreams might not have fully reached the final form we looked forward to when we handed over just the 23rd ever Edge 10 in E344's review, it's impossible to argue against the positive influence of this software. It has already led to young designer William Butkevicius (better known to the Dreams community by the username Eupholace, and his multi-Impywinning 3D platformer, Trip's Voyage) being recruited by Ori developer Moon Studios. Others who have cut their teeth on these tools – perhaps even some of those whose work we've spotlighted over the page, just a fraction of the wonderfully singular creations that can be found in Dreams – will surely follow.

With Tren mere weeks from release when we visit the studio, we find its creative director in a naturally reflective mood. How does Beech feel about Dreams now? "I'm incredibly proud of what we achieved with it," he says. "With my story of coming from the LittleBigPlanet community, it seemed so obvious for us to take that route. It's always been about empowering other people." Had he had the access to tools such as those featured in Dreams or LittleBigPlanet much sooner, he says, his career path might have been very different. "You know, I was just a builder," he says. "I've got no qualifications. I left school without any GCSEs. And it was just because I was doing stuff that was relevant that allowed me to move forward. So the more we can do that, the more tools we can put in people's hands – it doesn't matter whether it's Dreams or LittleBigPlanet or Minecraft, or any other game – I will always support that." And get more John Beeches into games? "I don't know about that," he laughs. "That sounds like a terrible idea."

That aspiration to fulfil the ambitions of a new generation of budding creators is poignantly expressed in Tren's finale – which, without giving the game away, represents a metaphorical passing of the torch to the Dreams community, just as a parent might hand down a beloved childhood toy to their offspring. Media Molecule's journey may have diverged from its expected route, but for many of Tren's players, the track is still stretching out in front of them. This is not the end of their dream, but the beginning.

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine, which you can pick up right now here.