MANILA, Philippines – President Rodrigo Duterte and his economic team have boasted that this administration would be remembered as the one that sparked economic growth through infrastructure.

The promise to smooth out bumpy roads, bridge towns, and solve Metro Manila’s "carmageddon" with fancy new trains resonated with Filipinos. While simultaneous constructions around the metro have worsened the traffic, commuters seem willing to endure the growing pains of development.

The cost of it all? Over P8 trillion.

Duterte’s economic team fought tooth and nail, cozied with global heavyweights like China, and even overhauled the country’s tax structure just to finance the ambitious plan.

Two years since Duterte’s rise to power, the burning questions now are: How fast are the projects moving? Can the Philippines really afford to repay debts incurred for these?

By the numbers

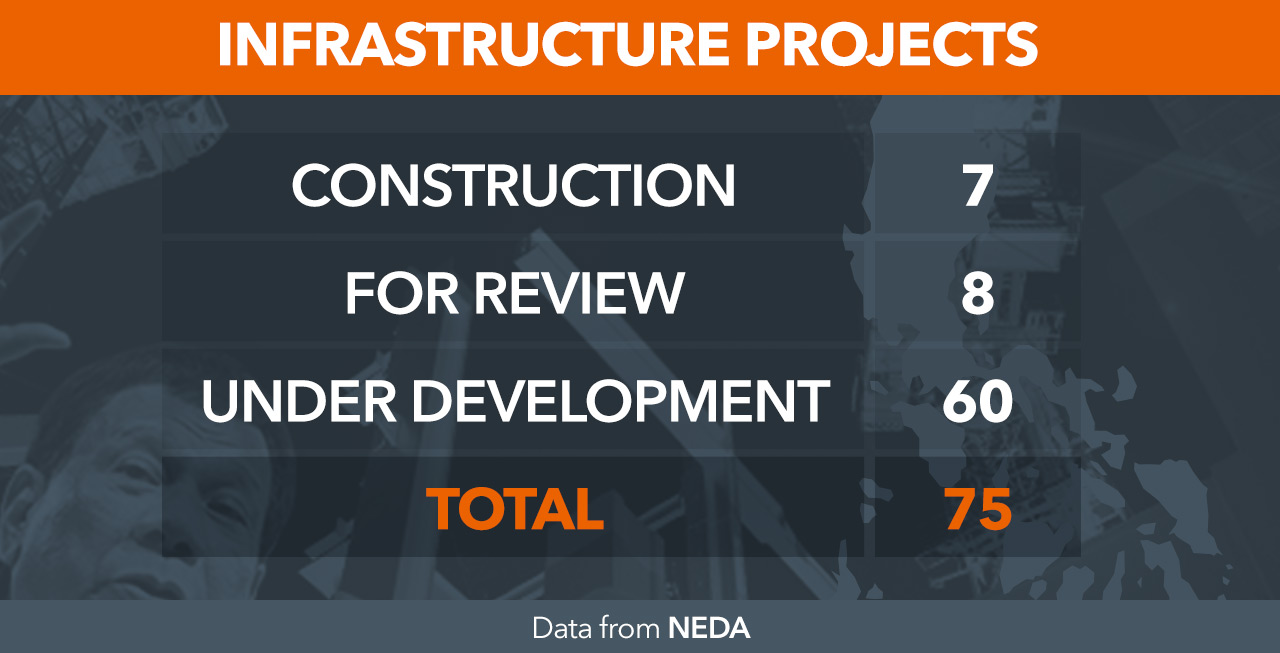

The government has over 2,000 infrastructure projects in the pipeline during Duterte’s term. The National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) has identified 75 flagship projects under the government’s Build, Build Build (BBB) program that are considered high-impact.

According to NEDA's timetable, 31 of the high-impact projects are supposed to start construction in 2018. As of writing, only 7 have started.

Works for the 3 components of Clark Green City (also referred to as New Clark City) commenced last January. Located in Central Luzon, Clark Green City will house satellite offices of all branches of government. It will also feature a commercial center, a disaster risk and recovery facility, as well as affordable rental housing units.

The construction of the Bonifacio Global City-to-Ortigas Center road link project started in 2017 and is moving along at a slightly faster pace than initially targeted.

Workers also started to build the components Chico River Pump Irrigation project last June. The P3.14-billion endeavor is the first project to commence construction under the Official Development Assistance (ODA) setup with China.

Meanwhile, the improvements along Pasig River from Delpan bridge to Napindan channel and Pulangi selective dredging projects are almost done.

Construction work for at least 19 projects are set to start in 2019, 11 for 2020, and 5 for 2021. Five more projects do not have a start date yet.

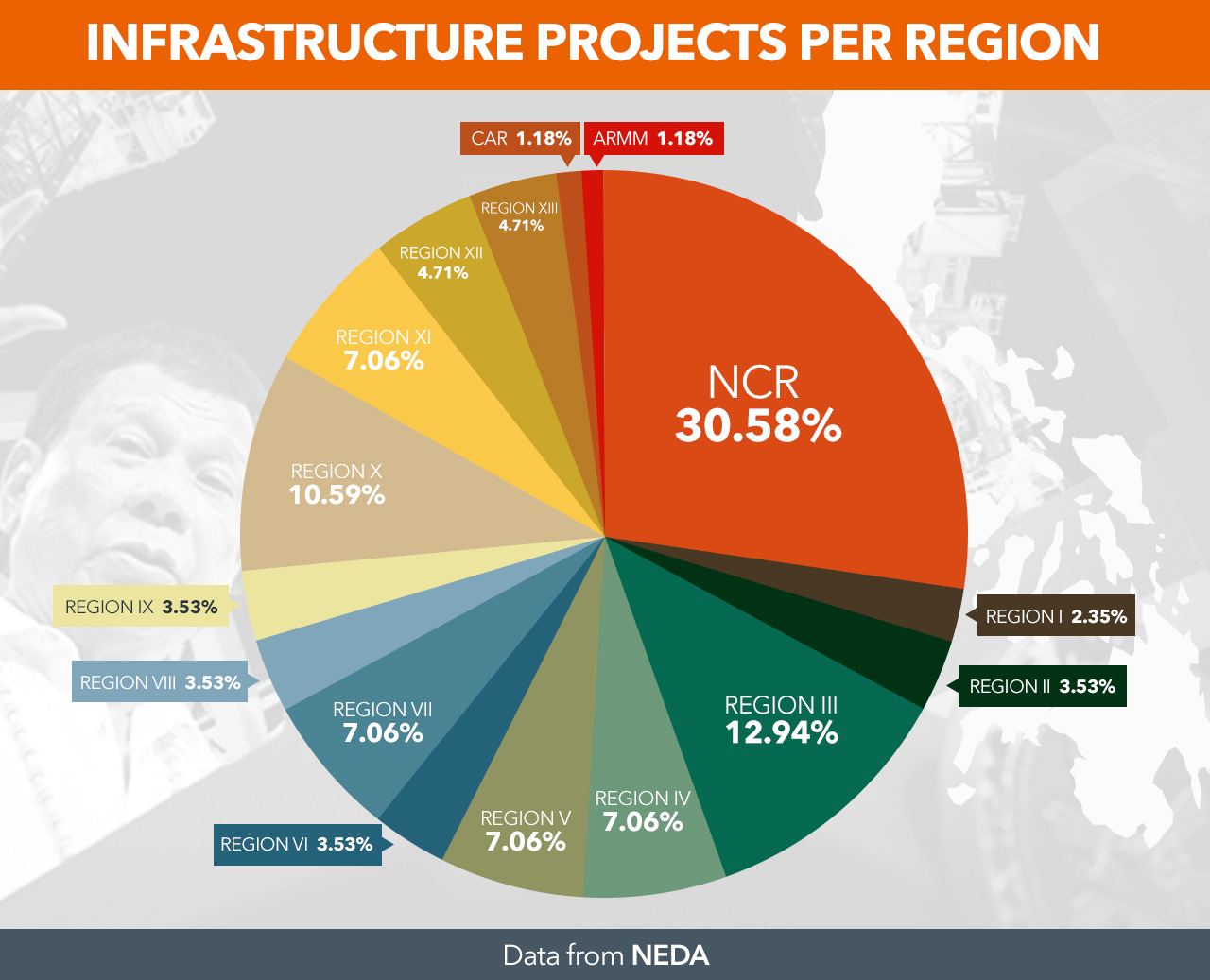

Most of the projects will be erected on various areas in the National Capital Region.

Eight projects are up for review and some might not see the light of day.

The Department of Transportation (DOTr) has put on hold the implementation of the 3 bus rapid transport (BRT) systems in Metro Manila and Cebu.

The P53-billion project aimed to create a dedicated lane for specialized buses and stations and was poised to solve heavy traffic.

However, Transport Secretary Arthur Tugade said the projects would actually be a “logistical nightmare” as the lanes may worsen traffic in narrow roads.

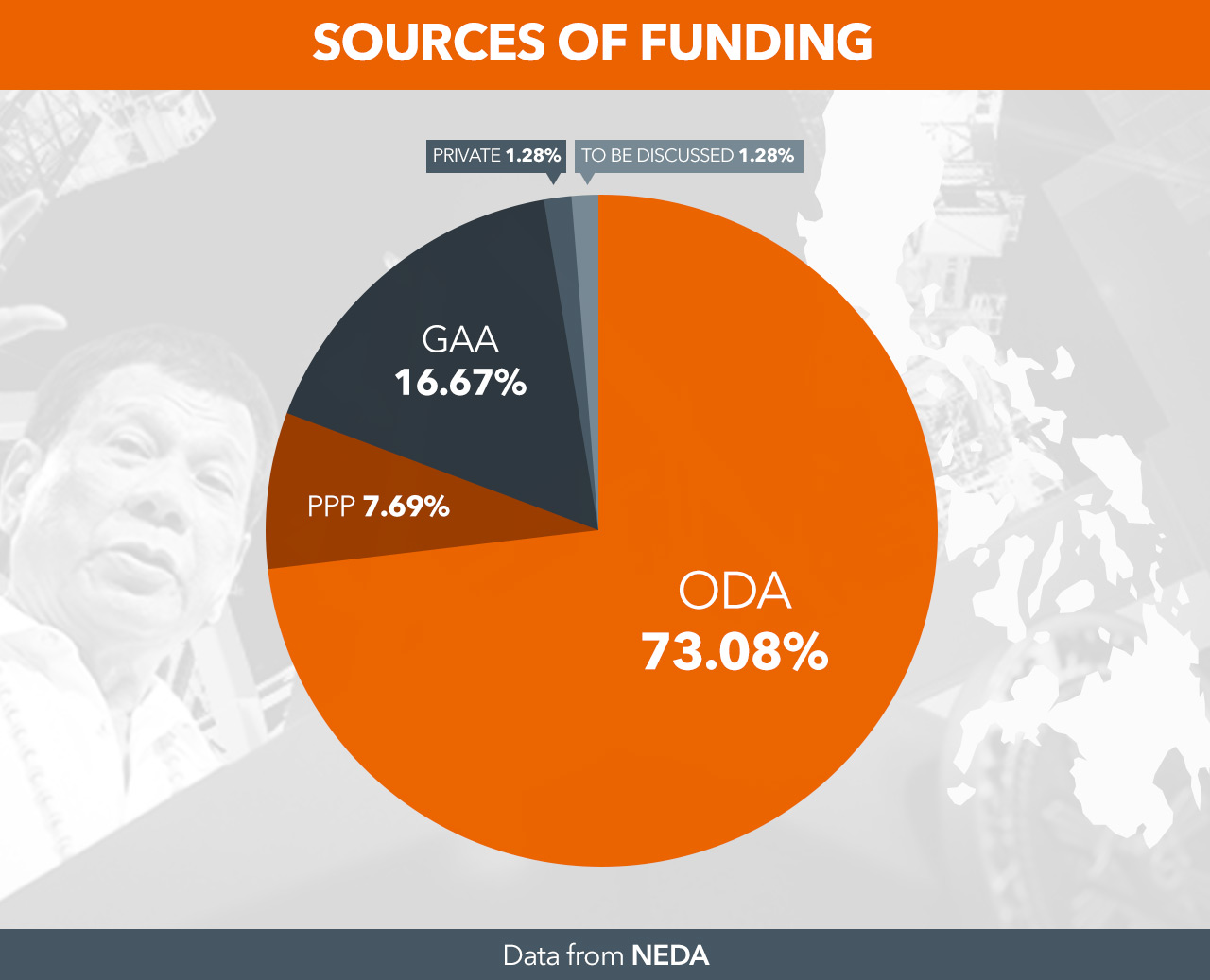

Most of the projects will be funded through ODAs (73.08%). At least 13 projects (16.67%) will be funded by the government under the General Appropriations Act (GAA).

The government has opted to lessen projects funded through Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) at just 7.69% of the total projects. At least one project (1.28%) will be funded by the private sector, while one more is still up for deliberations.

The most expensive among the projects is the highly-anticipated Metro Manila Subway project.The project is estimated to cost over P354 billion.

Phase 1 of the project is expected to serve around 370,000 passengers a day and will cut travel time from Quezon City to Taguig City to just 30 minutes.

The rail will start along Mindanao Avenue, pass by North Avenue, Anonas, Katipunan, Ortigas, Kalayaan, Bonifacio Global City, and will end at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport.

NEDA’s timetable stated that works should start this 2018 for it to be partially opened by 2022.

Other pricey projects are the PNR North 2 or the Malolos-Clark Airport-Clark Green City Rail (P211.43 billion), PNR South Long-haul or the Manila-Bicol line (P175.32 billion), and the PNR South Commuter Line or the Tutuban-Los Banos line (P124.14 billion).

All 3 PNR projects are currently under the procurement stage and should start construction by 2019.

Not included in NEDA’s list is the planned Bulacan airport project with a whopping P735.6 billion price tag.

NEDA Investments Coordination Committee has already approved the project to be spearheaded by Ramon Ang’s San Miguel Corporation (SMC).

Ang was quoted back in May as saying that the conglomerate could finance the project “easily” on its own.

SMC has about P1.38 trillion in total assets as of end-2017 and reported a profit of P54.8 billion that year.

Slow pace

While the government insisted that the infrastructure push is aggressive, the numbers tell another story.

For one, securing ODAs have been quite slow, to the point where Socioeconomic Secretary Ernesto Pernia even floated the idea of shifting the mode of financing for some infrastructure projects.

“There’s also a lot of red tape on the side of ODA [donor] countries. We thought that things would move fast, but they are not moving as fast as we expected…. If there are too many delays from a particular funding source, we are going to give them a deadline,” Pernia said in June.

Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III said the delays were caused by the Chinese government’s reorganization early in 2018.

In early March, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced plans to reshuffle and improve the bureaucracy.

Despite delays, the Philippines is bent on securing funding from China.

“We are planning to meet with them by the third week of August,” Dominguez said in a press briefing last July 4.

Meanwhile, agencies had their own struggles in implementing projects. The Commission on Audit flagged the inability of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) to effectively utilize funds.

COA revealed that P73.351 billion worth of infrastructure projects were either delayed, suspended, terminated, or unimplemented in 2017. The delay has cost the agency P27.647 million in commitment fees to banks.

“This indicates that management was not able to effectively manage the increasing amount of funds entrusted to the agency due to low physical delivery of target project and activities,” state auditors said.

DPWH Secretary Mark Villar blamed contractors and a long permit application process for the delays. Right-of-way acquisitions and road blockings also contributed to the delays.

He also said they had problems with their contractors, and would suspend 43 contractors involved in more than 400 projects.

"If a certain project is delayed by 15%, that is already critical. We require them (contractors) to come up with an action plan within an acceptable time period. If they can't follow their plan, we will cancel the contract," Villar said in a mix of English and Filipino.

Can the Philippines afford it?

Depite project delays, University of Asia and the Pacific senior economist Bernardo Villegas lauded the government's spending spree.

He said the Duterte administration is "light-years" ahead compared to the past governments in terms of implementation of infrastructure program.

But can the Philippines really afford them all?

During the deliberations of the first package of the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (Train) Law, senators estimated that around 80% of the funds for the BBB would come from loans. Less than 20% would come from revenues generated under the Train Law.

So where will most of this cash come from? China.

Duterte said he needs China “more than anybody else at this time" for the infrastructure push.

However, critics repeatedly warned that loans sought from Beijing could saddle the country with heavy debts. Loans from China generally have heftier interests of around 2% to 3%, as compared to Japan with only 0.75%.

China’s loans are at least 3 times more expensive than Japan’s, and at most 12 times more expensive.

A recent example of the so-called Chinese debt trap would be Sri Lanka. The country leased its China-funded port to China for 99 years due to its inability to repay debt. The port, in essence, has been taken over by the global superpower.

One need not look oceans far away to realize the threat of debt.

The infrastructure-related debt crisis under former president and dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the 1980s is a stark reminder of how public spending sprees coupled with corruption can bog down the country.

Pernia assured the public that the government is “extra careful” in dealing with China.

While economic managers have kept a watchful eye, the political sphere’s narrative tells a different story. Despite winning the arbitration case over the West Philippine Sea dispute, the Philippine government has been soft in asserting the decision.

The once bitter tug of war over maritime sovereignty between Manila and Beijing has turned into friendly ties, in exchange for dollars worth of loans, investment, and trade deals under Duterte.

Under Duterte's infrastructure spending spree, is it really all a win-win? or is there a dangerous trade-off in plain sight? – Rappler.com