The search for OceanGate’s lost Titan submersible captivated the world last week. Following the news that the sub had imploded on June 18 while descending to see the wreck of the Titanic, focus has now shifted to how the event happened.

Like many, I was saddened by the loss of the five people on board Titan. It was terrible news and a terrible loss. But it’s a loss we now know was preventable. As someone who has spent their career studying shipwrecks, crew and passenger safety should always come first.

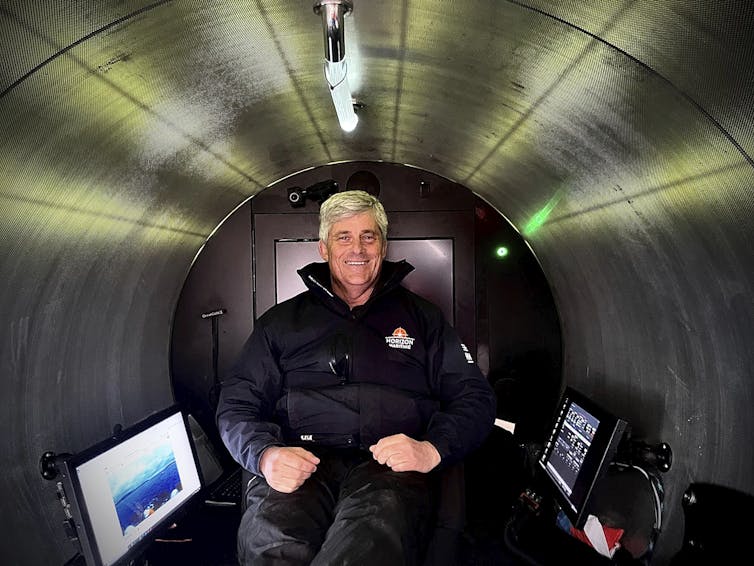

Stockton Rush, the CEO of OceanGate Expeditions who oversaw the design and construction of Titan, dismissed safety warnings about the sub as “baseless.” According to film director and deep-sea explorer James Cameron, members of the deep-diving community had long warned OceanGate about flaws in the Titan’s design.

The Titan disaster is reminiscent of a historic naval tragedy — the very same one the sub was heading towards during its ill-fated dive.

Tunnel vision

Like Edward Smith, the captain of Titanic, Rush also went down with his ship. And, as Cameron noted, both disasters could have been prevented if only each captain had heeded the warnings they received beforehand.

Smith disregarded telegrams from other ships earlier in the day warning about icebergs ahead. Instead of slowing his ship, he ordered full steam ahead, ultimately causing the loss of more than 1,500 lives.

In Rush’s case, he disregarded his company’s director of marine operations who pointed out serious flaws in the Titan’s construction. Rush’s response was to fire him.

Rush also disregarded industry experts and the members of the deep sea diving community, saying their safety regulations were too strict and stifled innovation.

The Titan disaster is also akin to a second historical disaster, the loss of British explorer Robert Falcon Scott. Scott died a month before the Titanic sank trying to be the first person to reach the South Pole. Like Scott, Rush’s expedition was ill-equipped and poorly managed, and he failed to listen to more experienced explorers.

The Titan’s fatal flaw

The Titan wasn’t designed like other deep sea submersibles. Most subs consist of a titanium sphere in which the crew sits. The sphere’s shape evenly distributes the ambient pressure applied to it as the submersible dives.

Size and shape matter underwater. The more people inside, the bigger the sphere needs to be. Most submersibles can house up to three people: a pilot and two passengers. The Russian submersibles, Mir I and Mir II, that Cameron used to make the movie Titanic, were of this type.

Rush figured he could build a five-person submersible by cutting a sphere in half and connecting both halves with a tube. Instead of using titanium, he used thin layers of carbon fibre sandwiched together — like a surfboard, only stronger.

Read more: What was the 'catastrophic implosion' of the Titan submersible? An expert explains

In addition to making the submersible bigger inside, carbon fibre also made the submersible lighter. If Rush had used steel, the submersible would have been too heavy.

The pressure hull of a submersible contracts when it dives and expands on its return to the surface. Titanium withstands this process much better than carbon fibre, especially after many dives.

Because Rush had never strength-tested the submersible’s pressure hull, he had no way of knowing how its carbon fibre walls would hold up. The walls were able to withstand the two previous dives to the wreck of Titanic. They did not survive the third.

Investigations into the disaster

As with the Titanic, there are now ongoing investigations into the Titan sub disaster. Both the U.S. Coast Guard and the Transportation Safety Board of Canada have announced their own investigations.

Rush wasn’t the only participant in this disaster. While not necessarily culpable for the disaster, anyone else involved will be able to provide authorities with information to help them understand the sequence of events that led up to the implosion.

While the Titan submersible was owned and operated by an American company, the ship that took the submersible out to the Titanic wreck site was Canadian. The Polar Prince will be able to provide investigators with vital information.

The Government of Canada will likely work closely with the United States, as it did in 1995 when negotiations began between the two countries to safeguard Titanic by introducing laws to prevent the wreck site from being looted.

The formalized agreement, which includes the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and France came into effect in 2019.

Preventing future disasters

Recommendations about how to avoid future disasters are forthcoming. Some have already been offered up. Charles Haas, the president of the Titanic Historical Society, said the wreck of the Titanic should now be declared off-limits to tourist submersibles.

While I understand and concur with his view, the issue isn’t so much about who dives to the Titanic, but how they get there. Diving should not happen unless crew and passenger safety is paramount.

While Rush was focused on his submersible’s flawed design, he overlooked the biggest rule of all: Keep your crew safe. In his blind quest for innovation, he failed to prioritize the safety of himself and his passengers.

As I wrote more than a decade ago, “the public’s lust for all things Titanic isn’t likely to die down any time soon.” The Titanic tourism industry is a lucrative business. But the bottom line remains: If anyone is to dive to the wreck they need to do so safely. No one’s life is worth the risk.

The way forward is more oversight. At present, regulating deep-sea exploration in international waters is challenging. But there is a possibility for governing bodies like the United Nations International Maritime Organization to take action to prevent future disasters like this from occurring.

Rob Rondeau does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.