It was 8:15 on a Monday morning, Aug. 6, 1945. World War II was raging in Japan and across Europe.

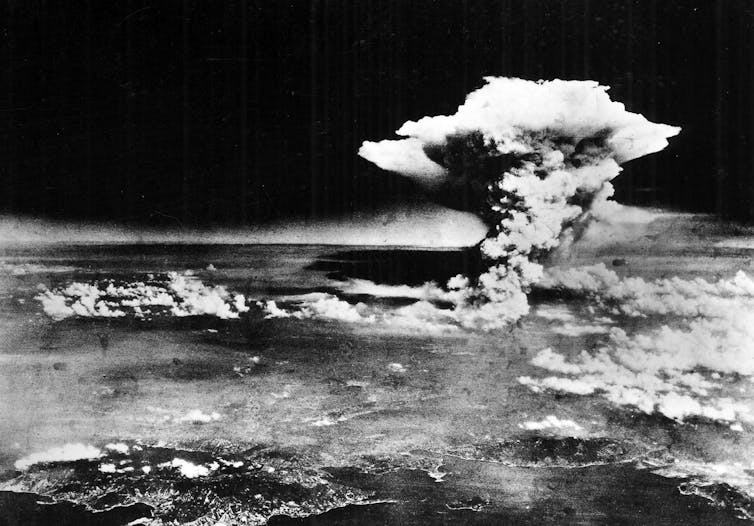

An American B-29 bomber dropped the world’s first atomic bomb over Hiroshima, Japan – an important military center with a civilian population close to 300,000 people.

The U.S. wanted to end the war, and Japan was unwilling to surrender unconditionally.

The bomber plane was called the Enola Gay, named for Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot.

Its passenger was “Little Boy” – an atomic bomb that quickly killed 80,000 people in Hiroshima. Tens of thousands more would later die of the excruciating effects of radiation exposure.

Three days later, U.S. soldiers in a second B-29 bomber plane dropped another atomic bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people.

It was the first – and so far, only – time atomic bombs were used against civilians. But U.S. scientists were confident it would work, because they had tested one just like it in New Mexico a month before. This was part of the Manhattan Project, a secret, federally funded science effort that produced the first nuclear weapons.

What might have been a single year of nuclear weapons development ushered in decades and decades of nuclear proliferation – a challenge across countries and professions.

Having worked on nuclear weapons both as a journalist covering the Pentagon and then as a White House special assistant on the National Security Council and undersecretary of state for public diplomacy, I understand how critical it is to educate and inform citizens about the dangers of nuclear war and how to control the development of nuclear weapons.

The man who started it all

Nobel Prize-winning physicist Albert Einstein warned then-President Franklin Roosevelt in 1939 that the Nazis might be developing nuclear weapons. Einstein urged the U.S. to stockpile uranium and begin developing an atomic bomb – a warning he would later regret.

Einstein wrote a letter to Newsweek, published in 1947, headlined “The Man Who Started It All.” In it, he made a confession. “Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in producing an atomic bomb, I would never have lifted a finger,” Einstein wrote.

Einstein repeated his regret in 1954, writing that the letter to Roosevelt was his “one great mistake in life.”

But by then it was too late.

The Soviet Union began its own bomb development program in the late 1940s, partly in response to Hiroshima and Nagasaki but also as a response to the Nazi invasion of their country in the 1940s. The Soviet Union secretly conducted its first atomic weapons test in 1949.

The U.S. responded by testing more advanced nuclear weapons in November 1952. The result was a hydrogen bomb explosion with approximately 700 times the power of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

A nuclear arms race had begun.

Arms control

The U.S. atomic bomb attacks on Japan remain the only military use of nuclear weapons.

But today there are nine countries that have nuclear weapons – the U.S., Russia, France, China, the United Kingdom, Pakistan, India, Israel and North Korea. The U.S. and Russia jointly have about 90% of the nuclear warheads in the world.

There has been progress over the past few decades in reducing the global stockpile of nuclear weapons while preventing the development of new ones. But that momentum has been uneven and oftentimes rocky.

The U.S. and the Soviet Union first agreed to limit their respective countries’ nuclear weapons stockpile and to prevent further development of new weapons in 1986.

And in 1991 the U.S. and the Soviet Union signed on to another legally binding international treaty that required the countries to destroy 2,693 nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges of about 300 to more than 3,400 miles (500-5,500 kilometers).

The two countries signed another well-known international agreement called START I in 1994, not long after the fall of the Soviet Union.

That treaty is considered by experts one of the most successful arms control agreements. It resulted in the U.S. and Russia’s dismantling 80% of all the world’s strategic nuclear weapons by 2001.

Russia and the U.S. signed on to a new START treaty in 2011, restricting the countries to each keep 1,550 nuclear weapons.

START II, as it is known, will expire in February 2026. There are no current plans for the countries to renew the deal, and it is not clear what comes next.

Complicating factors

Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine – and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s repeated threats to strike Ukraine and Western countries with nuclear weapons – has complicated plans to renew the new START deal.

Although Putin has not formally ended Russian adherence to the START II agreement, Russia has stopped participating in the nuclear inspection checks that the deal requires. This lack of transparency makes diplomacy over the deal more difficult.

Another complicating factor is that China has made it clear that it is not interested in an arms control agreement until it has the same number of nuclear weapons that the U.S. and Russia have.

Indeed, since 2019, China has increased the size, readiness, accuracy and diversity of its nuclear arsenal.

The U.S. Department of Defense reported in 2022 that China was on course to have 1,500 nuclear weapons within the next decade – roughly matching the stockpile that the U.S. and Russia each have. In 2015, China had an estimated 260 nuclear warheads, and by 2023 that number rose to more than 400.

At the same time, North Korea continues testing its ballistic nuclear missiles.

Iran is enriching uranium to near-weapons-grade levels. Some observers have voiced concern that Iran could soon reach 90% enrichment levels, meaning it would then just be a few months before Iran develops a nuclear bomb.

In a world of potential nuclear terrorism and conflicts that risk the unthinkable use of nuclear weapons, I think that the need to control proliferation and double down on arms control is a useful starting point.

So, what else can be done to contain the real threat of nuclear war?

Diplomacy is the way forward

Diplomacy matters, as was clear in the early years of U.S.-Soviet agreements.

In my view, a formal agreement between the U.S. and Iran to slow down its nuclear development would be valuable. Creating a better relationship between the U.S. and China might reduce the chances of a confrontation over Taiwan with the potential for a nuclear conflagration.

The U.S. can also use public diplomacy tools – everything from official speeches to international educational exchanges – to warn the world of the escalating dangers of unchecked nuclear weapons use. This is one way to get ordinary citizens to put pressure on their governments to work on disarmament, similar to how young activists have moved public opinion on climate change.

The U.S. could potentially use its global podium to underscore the horrific nature of threats that come with the use of nuclear weapons and make clear such use is inadmissible.

Remembering Aug. 6, 1945, is painful. But the best way to honor history is not to repeat it.

Tara Sonenshine does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.