Can an exhibition of work by a little-known Swedish artist change our understanding of avant-garde art? The history of early 20th-century art seems to be sufficiently set that the spectral appearance of an artist on the periphery of Europe wouldn’t change it in any way. However, the phenomenon of Hilma af Klint has opened up completely new avenues of study in our approach to abstraction.

Born in 1862, Hilma af Klint studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, where she developed a naturalistic style in keeping with her academic education. However, in the shadow of this official painting and, in private, she produced a completely different type of work.

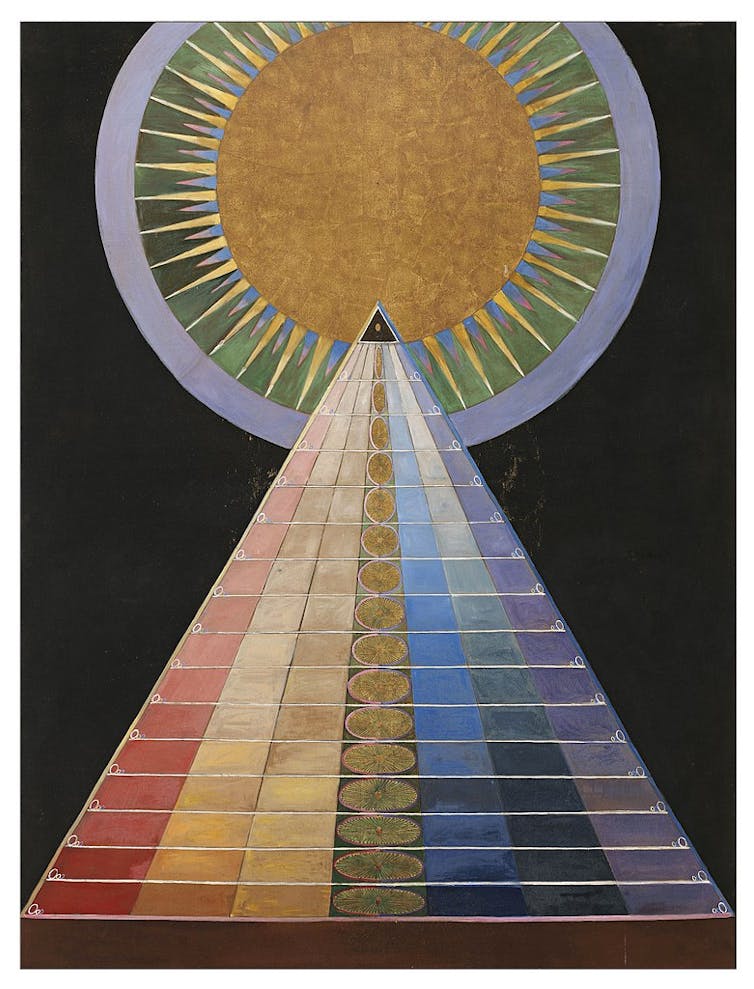

Together with four friends she formed the group De Fem (The Five), which held séances from which they derived sketches and instructions. Using these, Af Klint embarked on composing an abstract, symbolic and complex work that sought to represent the order of the cosmos.

This monumental work that Af Klint began in 1908 is now considered the first manifestation of abstraction.

Seeking inclusion in the canon

Although Af Klint’s work had been shown in a number of collective exhibitions before, in 2013 the Moderna Museet in Stockholm devoted a monographic exhibition to her , which revealed the breadth and brilliance of her oeuvre.

This had been hidden for 40 years at the artist’s wish, as she hoped that future society would be prepared to better understand her ideas. This seems to have been the case, as the exhibition was a success with both the public and the critics. After its presentation at home, Hilma af Klint began a tour of the world’s most renowned museums and travelled as far as the Antipodes.

The name of the original exhibition, “Hilma af Klint. Pioneer of abstraction”, made things clear: the Moderna Museet wanted to claim that the first abstract painter was Swedish. It was an attempt to introduce a new figure into the select canonical group of the great masters of the avant-garde, a woman in an eminently male list. The intention was not to change the narrative of contemporary art, but to complete it with a national figure.

That is why in the Stockholm exhibition De Fem only appeared at the end, in a tangential way, so as not to detract from the real and only protagonist. But the exhibition not only launched a new vein of merchandising, but also opened a hitherto veiled window. And out of it emerged the spiritualists.

The emergence of spiritualists

It was not the interest in the supernatural that came as a surprise: the relationship of many abstract artists to the doctrine of theosophy was well known, and some of its fruits, such as Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art, were widely disseminated. The surprise was that, following in the wake of Af Klint, studies began to emerge of women who, guided by their conversations with spirits, had experimented with abstraction as early as 1861, as in the case of Georgiana Houghton.

Suddenly, new artist mediums were appearing everywhere, and along with them a whole field of research that had previously been neglected. What began in Stockholm as an attempt to include a new actress in a well-structured story —- that of the masculine and rational avant-garde where a touch of spiritualism coloured the narrative – became an inescapable change of gear. Hilma af Klint was not a pioneer, but a leading member of a social and artistic impulse that went beyond her and had left a strong mark on the more experimental avant-garde.

New avenues for a richer and more complex history

The appearance of new authors has in turn encouraged the study of the relationship of other avant-garde artists with spiritual doctrines, and has made it clear that the occult, the esoteric and the spiritual had a fundamental place in the avant-garde.

It is also becoming clear that the protagonists of these trends were mainly women. As the artist Olivia Plender said, it is not surprising that the mediums were female, since speaking with the voice of another could be the only way to be heard. Nor is it surprising that these artists, writers and influencers of their time have been left in the shadows of a profoundly heteropatriarchal art history.

Now, the window that Hilma af Klint opened for us is widening, and another field of study is asking for its place in the foundations of the avant-garde: dance, closely related to esotericism and oriental cultures.

In 1944, Af Klint wrote in her will that her works would not be shown until 40 years after her death, when the world would be more ready to understand them. She was optimistic. It has taken almost twice as long, but it seems we are finally getting there.

Haizea Barcenilla does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.png?w=600)