When JD Vance stood to accept the vice-presidential nomination for the Republican Party, what struck me was his physical resemblance to Donald Trump’s sons. This is not surprising: Donald Jr had been his most active supporter. The best way to understand Trump’s choice is as a continuation of dynastic politics, a common theme in recent US politics — think Kennedy, Bush, Clinton.

This is not the standard explanation for Trump’s choice, which emphasises Vance’s links to conservative money in Silicon Valley and right-wing media figure Tucker Carlson. But for Trump, politics is an extension of the family business and Vance has cleverly positioned himself as a de facto son.

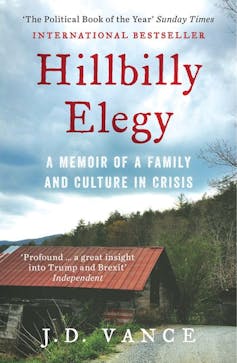

Vance rode to popular attention – and then a Senate seat from Ohio – on the basis of his 2016 book Hillbilly Elegy. This is not unprecedented in US politics: Barack Obama’s Dreams From My Father (1995) helped launch his political career, just as John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage (1956) was a deliberate ploy for public attention.

Neither book was as immediately successful as Vance’s, which became a bestseller and the basis for a movie of the same name. His mother was a drug addict who married and changed boyfriends several times, giving him various stepfathers, so his grandmother was his most stable mother figure.

But his grandparents’ marriage was violent, and at one point his grandmother tried to kill her husband by setting him on fire. They separated, but effectively reunited (despite living separately) as he was growing up, giving him stability – they had considerably mellowed by the time Vance was a boy. After scraping through high school, he joined the Marines and went to Ohio State University.

Older readers may recall the 1960s television series The Beverley Hillbillies, which suggests the ongoing fascination with understanding a section of American life in which poverty and violence appear to persist over generations.

A memoirist like Obama

In some ways, Vance’s book resembles Obama’s memoir. Both recount stories of men clearly not part of the WASP establishment, who were determined to achieve greatness. Like Obama, Vance attended an Ivy League law school – Yale, rather than Obama’s Harvard – where, like the Clintons, he met his future wife.

In the Marines, Vance writes, he learned “willfulness”, perhaps as opposed to the “helplessness” he learned at home.

Obama became a community organiser, whereas Vance became a venture capitalist with backing from one of Silicon Valley’s conservative moguls, Peter Thiel. One of Vance’s attractions for Trump was his ability to raise money from very rich donors, who might not like Trump’s rhetoric but certainly appreciate his views on taxation, which are skewed heavily towards favouring the rich.

Obama is the better stylist, but Vance is a competent and vivid writer, even if the complexities of his childhood, torn between a mother who becomes a drug addict, numerous de facto stepfathers and his grandparents, makes for harrowing reading. As a picture of a complex dysfunctional family, it is a remarkable if somewhat maudlin achievement.

Occasionally, Vance acknowledges the similarities between rural poor whites and African–Americans, and the book has none of the nasty racist language deployed by Trump. Although Vance has become an arch social conservative, there is none of the ugly homophobic language of some of his colleagues.

As a teenager, he wondered about his sexuality, to which his grandmother replied:

You’re not gay. And even if you did want to suck dicks that would be okay. God would still love you.

Here Vance reveals a softer sense of sexuality and gender than is found in many of Trump’s evangelical supporters. “I learned little else about what masculinity required of me,” he writes. “Other than drinking beer and screaming at a woman when she screamed at you.”

Vance grew up in Middletown in eastern Ohio, but stresses his Scots–Irish ancestry and small-town, coal-country Kentucky roots. He begins the book claiming his great-grandmother’s Jackson, Kentucky house, where he spent childhood summers, as his true “home”, though his grandparents were among many who left for Middletown (consequently nicknamed, he claims, “Middletucky”). The working-class industrial town was part Appalachian and part Rust Belt.

He stresses the long history of disadvantage in the Appalachians, a region that stretches across seven states, from Alabama to Pennsylvania. (There are considerable variations in what is considered part of the Appalachian region.)

Traditionally Democratic, the region has swung increasingly to the Republicans, symbolised by the shift in West Virginia, which supported Bill Clinton twice – and then voted around 60% for Trump in the past two elections.

This is a region of small towns and rural communities, heavily white and dependent on timber and coal mining. While Pittsburgh is sometimes included in definitions of the region, it has no major cities.

Intergenerational disadvantage and self-reliance

Hillbilly Elegy is in some ways a schizophrenic book, which both acknowledges the burdens of intergenerational disadvantage and preaches the virtues of self-reliance.

When it appeared, it attracted both conservatives and liberals, although Vance was heavily criticised for ignoring the structural causes of disadvantage. Most savage, perhaps, is the critique by Gabriel Winant, who actually knew Vance when he was a law student at Yale.

As Winant points out:

Vance wishes to foment what he sees as a class war — not between labor and capital, but between the white citizenry and the “elites” of the universities and the media, who pour poison into the ears of the country and corrode its virtue and integrity by stripping away your jobs, corrupting your kids, and sending drug-laden foreigners into your community.

This Trumpian rhetoric is not the language of Hillbilly Elegy. There are echoes in his book of Ronald Reagan’s attacks on “welfare queens”, but without the racism. As Vance writes: “I have known many welfare queens; some were my neighbors, and all were white.”)

The book elicited a remarkable amount of commentary, including an anthology, Appalachian Reckoning, which took issue with Vance’s characterisations of the region, claiming “Vance’s sweeping stereotypes are shark bait for conservative policymakers”.

Both conservatives and liberals could, however, agree that Vance had captured the mood that saw many traditional Democrats swing to Trump. The party of unions and non-white Americans was increasingly painted as the captive of Wall Street and Hollywood elites. This helps explain why Hillary Clinton lost in 2016 and why Joe Biden, who comes from working-class roots, was able to recapture some of those lost votes in 2020.

Vance traces his own similar disillusionment, dating back to his first employment as a teenager:

Every two weeks, I’d get a small paycheck and notice the line where federal and state income taxes were deducted from my wages. At least as often, our drug-addict neighbor would buy T-bone steaks, which I was too poor to buy for myself but was forced by Uncle Sam to buy for someone else.

This, he writes, was his “first indication that the policies of Mamaw’s ‘party of the working man’ – the Democrats – weren’t all they were cracked up to be”. And, he believes, it’s “a big part” of why “Appalachia and the South went from staunchly Democratic to staunchly Republican in less than a generation”.

If one wants an explanation of how so many poor Americans could vote for a candidate who boasted of his wealth and promised increasing tax cuts for the rich, there is perhaps a more sophisticated analysis in Arlie Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land, also released in 2016, on the cusp of Trump’s election. Her book explores the appeal of Trump in the bayou country of Louisiana, an area that shares some similarities to Vance’s Appalachia.

But the Vance who wrote Hillbilly Elegy has undergone a major political transformation since the 2016 election, when he attacked Trump as “cultural heroin” and mused whether he might be “America’s Hitler”. One assumes much of this is sheer calculation, but I suspect there is more to his new conservatism than sheer ambition.

Religion and skepticism

As a younger man, Vance was suspicious of religion, after a brief stint as “a devout convert” to the evangelist Christianity of his largely absent father. He writes: “the deeper I immersed myself in evangelical theology, the more I felt compelled to mistrust many sectors of society”.

Four years ago, Vance converted to Catholicism, writing that he saw in Catholicism a recognition “that we are products of our environment; that we have a responsibility to change that environment, but that we are still moral beings with individual duties”.

It’s hard to find fault with that sentiment, but his Catholicism also helps explain his rigid line against abortion, a key issue in US politics since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. His is not the Catholicism of Biden, who accepted the right of women to choose, but seems to be more in line with conservative critics of Pope Francis.

In that article, he also writes that he “left for Iraq in 2005, a young idealist committed to spreading democracy and liberalism to the backward nations of the world”. And that he “returned in 2006, skeptical of the war and the ideology that underpinned it”.

Vance is often attacked for being an isolationist, abandoning the global leadership role most US presidents have championed. But here he is close to those on the left who, like him, reflect on the carnage of recent interventions in places like Iraq and Afghanistan. Vance is aware most of the recruits to the US armed forces are not liberal college graduates, but poor and often non-white Americans, whose deaths and injuries seem largely pointless.

The vice president has little actual power, other than to preside over the Senate, where Kamala Harris has used her casting vote to further a number of Biden’s initiatives. In a sense, it is a role rather akin to that of the Prince of Wales, where much of the job is anticipation of the future. Presidents often use the position to pick the person they hope will succeed them, although Obama overlooked Biden in 2016 to support Hillary Clinton.

If elected, Vance’s real challenge will be to keep in favour with Trump for the next four years, with the clear expectation he is the heir apparent. The media discussion of his policy issues seems to me overblown: Vance will go along with what Trump wants and, as experience has taught us, Trump’s views are a movable feast, politely called transactional.

Vance is more cerebral than Trump and certainly better-read, but his politics have changed since he wrote Hillbilly Elegy. He will certainly be aware that if they win, Trump will be in his eighties by the end of his second term and constitutionally unable to recontest. Don Jr, Eric and Ivanka may well be preparing to serve in a future Vance administration.

Dennis Altman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.