In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

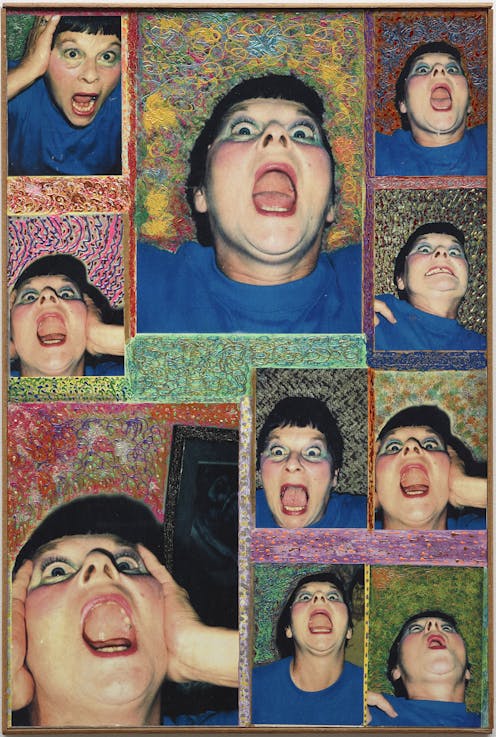

Ten images of a woman screaming with theatrical rage, pasted onto board, decorated with glitter paint. The faces she makes are almost comic, but there is an intensity to them. The title, Pat’s Anger, says it all.

In 1992, the year of her first exhibition, Australian artist Pat Larter wanted her husband, the artist Richard Larter, to understand how his unconscious selfishness made her feel.

She asked her son, Nicholas, to make multiple digital close-up photographs of her face as she lay on the carpet, and arranged the subsequent prints to show to Richard with the comment: “This is how you make me feel.” It was about this time that Richard’s diaries stopped referring to “my house” and changed to “our house”.

Images of Pat dominate Richard Larter’s figurative work. Deborah Hart, now Head of Australian Art at the National Gallery, once described her as “one of the most painted, drawn, photographed and filmed artist-partners in the entire history of art”.

In 1971, Richard’s Pop-influenced paintings of Pat’s body in various guises led the art historian Bernard Smith to describe him as “probably the most original talent to emerge in Australia in recent years”. Even though Richard regularly spoke of Pat’s importance, Smith did not notice her.

It took many years for Pat to be recognised both as a major influence on her husband’s work and as an artist in her own right.

Pat met Richard when she was 15, on her first day of work as an office junior. She was from a poor London family; he was the discontented son of a politically conservative, artistically aware family. He introduced her to cinema, she introduced him to theatrics and burlesque humour.

In 1962, with three children in tow, the Larters emigrated to Australia. Richard had unsuccessfully tried to exhibit his art in London, but here he came to the attention of Frank Watters and Geoffrey Legge, who were interested in new artists for their recently opened Watters Gallery in Sydney.

The Larters bought a house at Luddenham in the hinterland south-west of Sydney. Two more children were born. While Richard painted after finishing his day job, Pat entertained the children with dress-ups, tap dancing and performances as “the world’s worst ballerina”. These continued after they bought a television, but stopped when Richard commandeered the living room so he could make larger paintings.

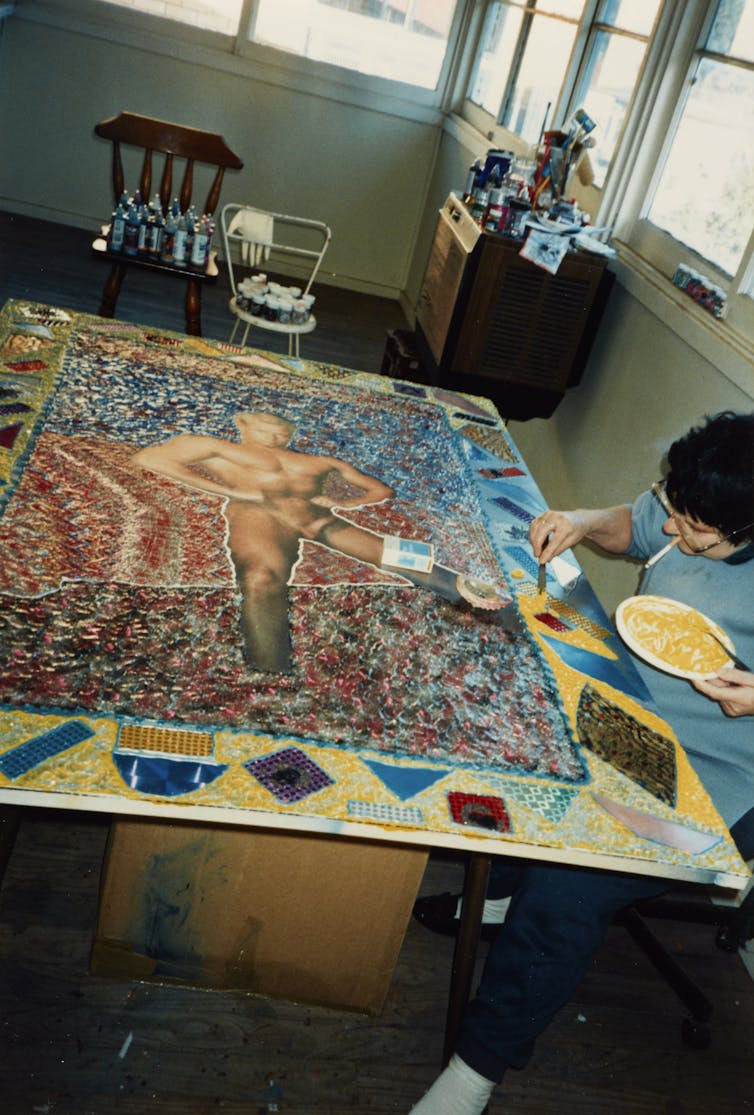

She had always posed nude for him, but now he began to incorporate elements of her costume in his paintings. She appeared as a stripper, a risqué schoolgirl, a naughty maid. Sometimes he painted her full-frontal – challenging viewers to comment on her exposure.

In 1969 they began to make experimental films, initially on a super-eight camera. Stills from these, showing Pat in various poses, were incorporated into the subject matter for Richard’s paintings.

Although Pat initiated many of the performances, the (male) critics and curators who admired the result gave credit to Richard Larter alone. This was not unusual for the time.

She was nobody’s Pat

In 1974 Richard was appointed visiting artist at the Elam School of Art in Auckland. Pat participated in his lectures here, which evolved into performances.

The head of sculpture at Elam at the time, Jim Allen, attracted many international visitors. In 1974 one of these was Terry Reid, a visiting Canadian artist who initiated the international mail art event for Auckland.

International Mail Art had its origins in postcards exchanged by Dada artists in the 1920s. It had grown into a significant movement of creative anarchy where artists, many of them from countries under political oppression, would exchange postcards. The recipients would sometimes add to them before forwarding the cards on. By the 1970s, dominant figures in the movement would stage thematic mail art events.

In Auckland, artists were invited to send works of precisely one inch in size. Pat’s entry was called “Barely an Inch Dared”. Reid said of her work:

[it was] perfect … She had actually made prints from her body and each was a perfect inch … an inch of elbow, or clitoris or whatever and so … No part of the body became more important or more special than any other part which I thought was a really nice thing to do.

When the Larters returned to Luddenham, Pat began to send and receive mail art in an ever-growing practice. She enjoyed exploring and ridiculing sexual politics, inventing the feminist mail art term, “Femail Art”.

She used children’s stamp sets to make punning slogans: “Oh Pun Legs”, “Mamaries”, “Self Exposure”. When a Brazilian artist assumed her explicit works were an invitation for mutual masturbation, she incorporated his offer into her reply, stencilling, “She’s nobody’s Pat”.

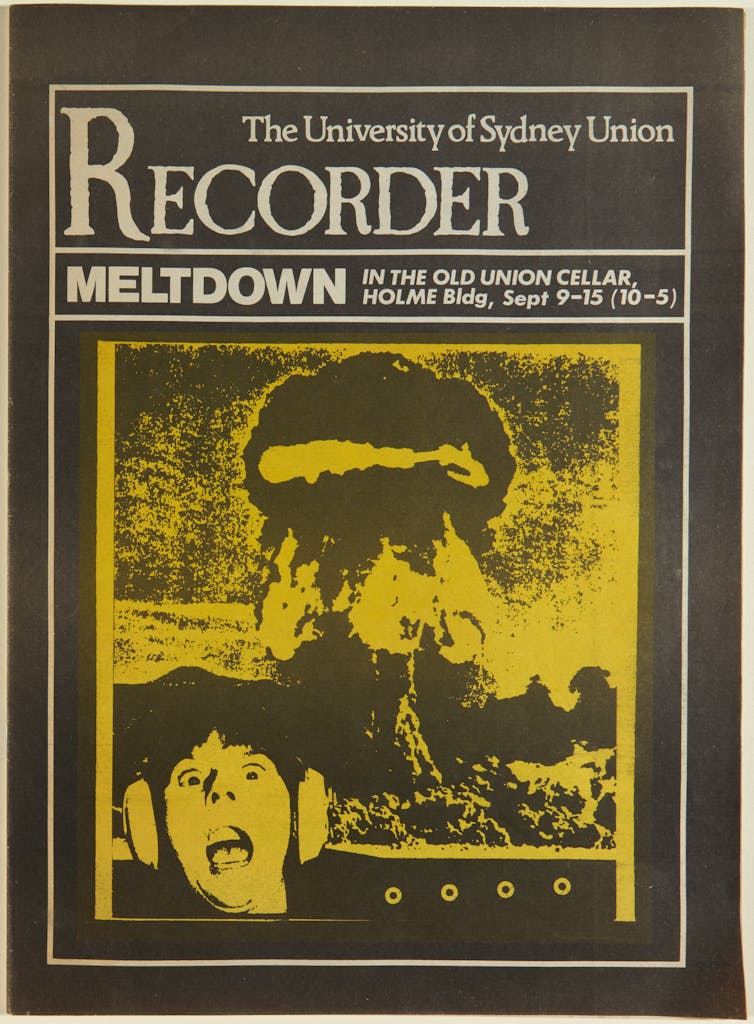

Pat was also involved in a mailart show protesting French nuclear tests in the Pacific, the promotional poster for which shows her screaming face, encouraging artists from around the world to protest against nuclear power.

She also continued to make films. Most were with Richard, but Men (1975) is a solo effort where the viewer is taken from the sign on a toilet block to linger over bronzed bodies on a beach. She described this as giving men “the Playboy treatment”, where the final contrast was between a muscle-bound man’s torso and a classical marble statue.

This challenge of the nature of gaze influenced her sexualised political performances in the anarchic Mahouly-Utzon Performance Troupe. Most dramatic of all was Tailored Maids, a critique of female circumcision where she sat behind a sheet, using shadow play so that as the implements of destruction – including secateurs – approached her body, she threw pieces of raw meat into the audience.

An artist in her own right

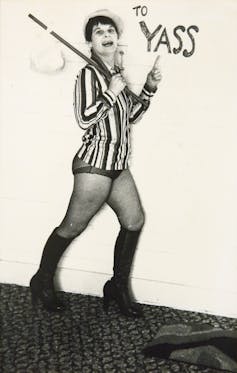

In 1982 the Larters sold the property at Luddenham and moved to the centre of Yass township. The departure is recorded in a mail art postcard showing Pat’s celebratory performance. Tellingly, the National Gallery of Australia’s catalogue credits this work as being solely by Richard Larter.

In 1989, on a visit to Canberra, Pat saw an exhibition of work by Aboriginal women from Utopia in the Northern Territory. She was fascinated both by their art and the fact that they painted with the work flat on the ground. By this time Pat had ceased to model for Richard. Her knees especially were too painful for any more posing.

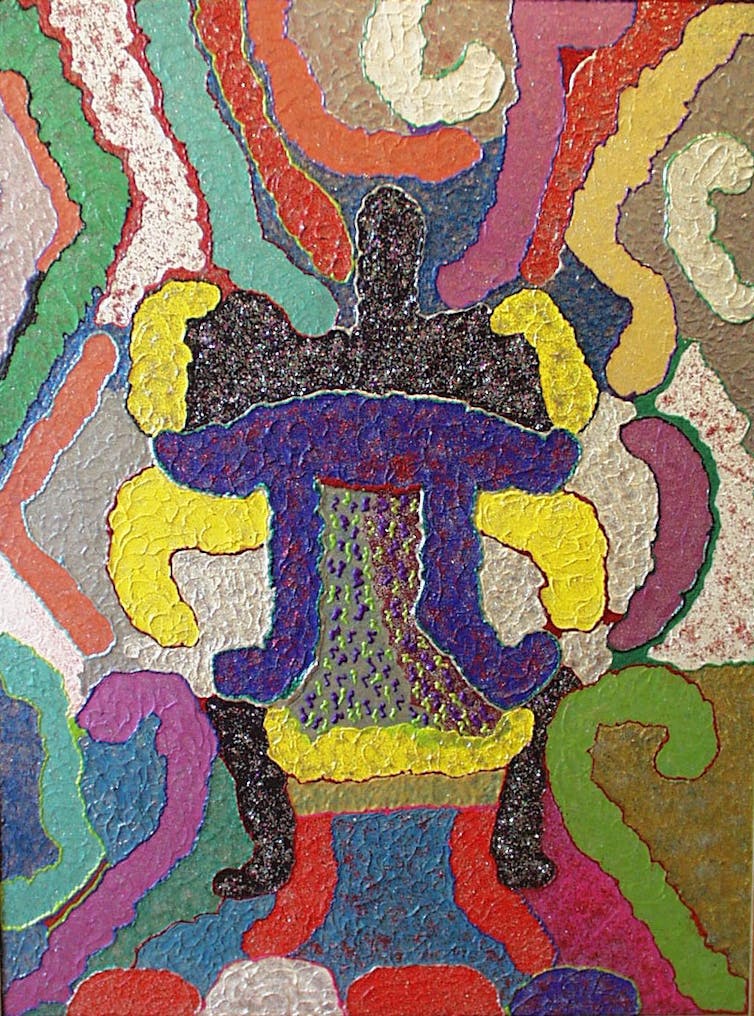

Inspired by the Utopia artists she began a series of abstract paintings as visual reactions to music, placing the boards flat on the kitchen table. She did not want to use Richard’s colours, but instead bought craft paints and glitter from the local craft shop. In 1992 she held her first exhibition at Legge Gallery.

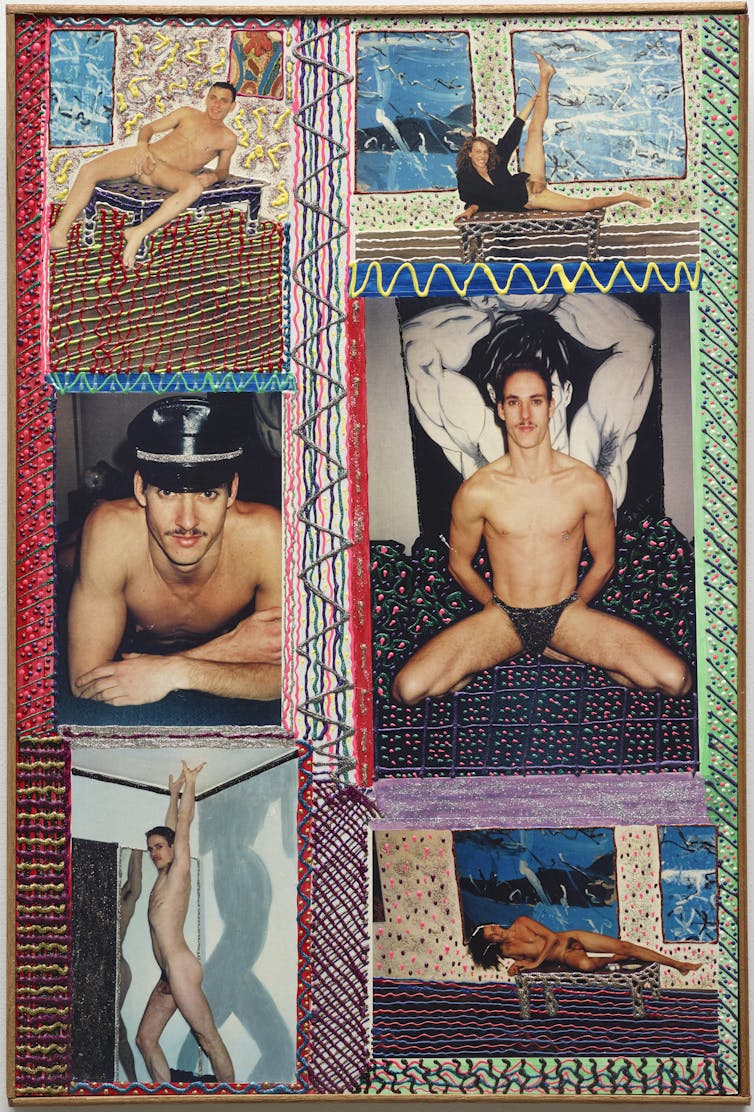

Both Pat and Richard were enthusiasts for the newly available Super Scan laser printer, which enabled giant colour photographs. Pat’s subjects were men, photographed in a Sydney brothel, posing as beefcake, confronting the viewer, enhanced with glitter paint. Her work was included, along with that of her husband, in the 1996 Adelaide Biennial at the Art Gallery of South Australia.

Read more: How our art museums finally opened their eyes to Australian women artists

Later that year, a persistent pain in her back, along with her aching legs, led her to seek a specialist’s opinion in Canberra. By the time a diagnosis of lymphoma was made, she only had weeks to live. Pat Larter died on October 14 1996.

Following her death, her family and friends, especially Richard, were concerned that she be remembered as an artist in her own right. He gave the Pat Larter archive to the Art Gallery of New South Wales. In 1999 Steven Miller, the Head Research Librarian, curated the first exhibition of Pat’s mail art and Larter films. The Legge and Watters galleries continued to exhibit her work, and gradually her paintings have entered public collections.

In 2006 Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre organised a touring exhibition Larter Family Values, honouring both Pat and Richard Larter. More recently a new generation of feminist artists have come to appreciate the radical nature of her art, which still challenges (some) of today’s viewers.

Joanna Mendelssohn was the curator for Larter Family Values. She has in the past received funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.