Augusta Theodosia Drane, a 19th-century English religious leader, published works including poetry, histories, essays and biographies. Impressively, Drane wrote her two-volume life of St Catherine of Siena in a matter of six weeks. The book was the most complete life of the saint in any language and was translated into German and French.

Yet few people these days know Drane’s name.

This is surprising because her story resonates with our modern world. From early on, she knew she did not want to marry and abhorred the idea of being on the marriage market.

Moreover, in some of her poems the speaker is clearly male, as was Drane’s acquired religious name Francis Raphael. These days we might potentially call her queer, though this is speculation. In any case, she is a fascinating figure.

A precocious child

Drane was born in 1823 to a prosperous family living near London. She was a precocious child and prolific reader: according to her memoir, “up to the age of 19, I had few friends, but I had read many books.”

She was excitable and apparently naughty, behaviour attributed to a “brain-fever” in early infancy. However, the main extent of her naughtiness seems to have been a high intelligence coupled with an independent mind and an understandable disinclination to grammar and mathematics.

A top student, she skipped several grades, but drew the ire of a teacher who felt she was “not prim and neat enough”. Yet another teacher understood her strengths, nurturing her interests in natural history, literature and the Bible.

Drane’s family was Anglican. In 1850, after three years of grappling with her faith and suffering the death of her beloved mother, she converted to Roman Catholicism. She was 26 at the time. Her father reluctantly accepted her decision. Her sister would later become a Catholic too.

In 1852, Drane joined the Dominican Congregation of St Catherine of Siena, then based in Clifton, England. The Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1829 had given Catholics full civil rights. Even so, Catholics were still barred from studying at Cambridge and Oxford until 1871.

The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception (Mary’s preservation from the guilt of Original Sin), declared in 1854, had a lasting impression on Drane. Not long after, she would take on the religious name of Francis Raphael of the Immaculate Conception. Drane joined an order with a special devotion to Mary, a community of women overseen by a woman with the title of Mother. She would eventually become a Mother Superior and, ultimately, Mother Provincial in charge of all the nuns in the order.

Drane’s decision to choose Mary, celibacy and the convent did not simply signal her commitment to her new faith; it also repudiated Protestant Victorian family values and the expectation that women would marry and bear children.

Catholic sisterhoods in England came under enormous suspicion, partly because they were led by women. Men were largely redundant to the running of a convent. Moreover, these religious communities were chiefly active rather than contemplative. Thus, by focusing on areas of community need, such as education, or helping orphans or fallen women or the elderly, the working nuns obtained relative financial security.

Warrior lovers

Drane believed the life of a nun was intimately bound up with a love for Christ. Yet she acknowledged it was by no means an easy kind of love. Nuns often risked health and safety in the slums of England or the remote corners of empire — all for Christ.

As Drane exclaims in her poem Sensible Sweetness, “We dare not shrink from work in His dear Love begun.” Drane’s Songs in the Night and Other Poems was first published in 1876 and the volume had an impact on its readers for its spiritual insights.

She remarks in her memoir,

It is the only book of mine that I know for certain has done good to others, because they have told me so.

Drane declares in her poem Dartmoor that the religious life “tread'st a harder way”. This quality of hardness translates to the notion of the nun as masculine. Drane believed that characteristics often associated with manliness, such as courage, strength and independence of spirit, were cultivated through hard work rather than being innate.

The garb of masculinity enabled Drane to describe herself and her vocation in the language of a warrior nun. The concept derives part of its language from the Song of Songs, which describes the bride’s neck as “like the tower of David”, armed with the shields of warriors.

A similar image is of the bride being as majestic as an army with banners. Nuns saw themselves as brides of Christ.

Drane’s superiors recognised and encouraged her writing talents. Her wide-ranging interests included religious warfare and military orders, exemplified in the publication of a book about the Knights Hospitaller, a medieval Catholic military order founded in the Holy Land originally to care for sick pilgrims, which also came to defend the Crusader kingdom. Published anonymously in 1858, the book was admired by military men who were shocked to discover its author was a nun.

The book’s preface praises members of the order for their “determined courage and heroic devotion”. Likewise, in her poetry Drane holds the life of a nun to be as valorous as that of these warriors: “Wring out the sweetness from thy life, / And gird thy loins for nobler strife,” she says in Dartmoor.

In this poem, the speaker seeks a higher cause and resolves to live a heroic life by turning his back on the “soft, voluptuous green”.

Unconventional

Although we might be projecting our current worldviews on to the past, a researcher might ask if Drane was what we would today call queer.

From an activist perspective, this line of thinking potentially enables sexual minorities to carve out a place for themselves in history, which is often “straightwashed” by scholars. At the very least, an exploration of Drane’s relationships could well expand our contemporary understanding of intimacy, friendships and “soulmates”.

Drane was certainly unconventional in her attitude to marriage. From an early age she understood she was neither destined for London seasons, nor for courtship and marriage. Such things she “held in abhorrence”, according to her memoir. She was much more interested in the virtues of poverty and issues of theology.

The solitude of religious life restricted the number of close friendships she had. At the same time, the realisation that such a life was a lonely one enhanced the need for human companionship within the context of one’s love for Christ. These friendships could be especially passionate.

Thus, Drane’s dearest friend and mentor, Mother Imelda Poole, addresses her in a letter as “my very dear sister, and true yoke-fellow”, expressing gratitude to God for granting, “even in this world, such a great blessing as a perfect union of two hearts in Him!”

Drane’s memoir describes her “lifelong friendship” with Poole as “one of the special graces, as well as the greatest joys” of her life.

Poole possessed intelligence, wisdom and an understanding of her friend’s character as she helped guide her through her early trials as a novice.

It’s difficult to conclude if the two women were queer according to our modern definition of the word, or even queer (strange) in the Victorian sense. (Either that or the Victorians were queerer than we are today.) Yet Drane’s memoir records how Poole was indeed her soulmate. After Poole’s death in 1881, she writes:

During these last ten years, union in work, union in daily and hourly intercourse, have made up such entire union of soul, as I did not think was possible in this poor world.

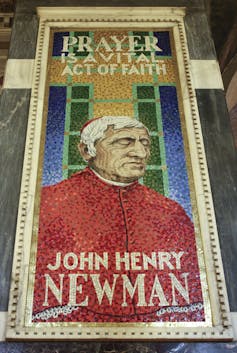

That the depth of their friendship could be discussed so openly in letters and published in Drane’s memoir suggests this and similar relationships, such as that between fellow convert Cardinal John Henry Newman (the most famous Catholic of the era) and Ambrose St. John, another Catholic priest, were publicly accepted and almost certainly admired in Catholic circles.

American scholar Sharon Marcus argues a range of relationships between women, including those in which they simultaneously “wrote of love for God and love for female friends with equal erotic fervor”, formed an essential element of Victorian society.

In fact, Marcus notes, “People who thought of God as a friend easily linked friends to God”. If Drane did have queer desires and remained celibate, I believe such desires could still fall within the expansive Victorian concept of friendship, which allowed for a depth of emotional intimacy comparatively rare today.

‘He loves me!’

Possessing a vivid imagination and active intellect meant the restraint and monotony of convent life was a trying change in the novitiate. As a novice, Drane heard Bishop William Bernard Ullathorne, the first bishop of Birmingham, give a speech on the personal love of Christ for each soul. His words had a profound impact on her spiritual devotion. She says in her memoir,

When in my cell alone, I lay prostrate on the floor in a sort of ecstasy. I could not sleep for three nights, but lay broad awake, thinking, ‘He loves me! He loves me myself with a personal love!’ I could hardly touch food. There was a complete revolution in my spiritual life, and the solid grace lasted when the sensible devotion was withdrawn.

This mania or hypomania could well have been an intense religious experience or it could potentially point to bipolar disorder and/or another category of neurodivergence, especially coupled with Drane’s periods of deep depression and times of prolific creativity.

Drane died in Stone in April 1894, aged 70, following a bout of pneumonia and incurable gangrene in her right foot. She was laid to rest next to the bodies of her two predecessors, including her friend Mother Imelda Poole.

Her final words were, “Is this dying? Will it be long?”

Duc Dau received funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.